C-peptide

| |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChemSpider | |

| MeSH | C-Peptide |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

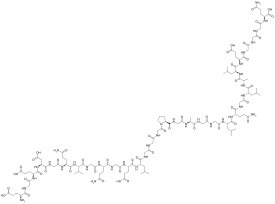

| C129H211N35O48 | |

| Molar mass | 3020.29 g/mol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

The connecting peptide, or C-peptide, is a short 31-amino-acid polypeptide that connects insulin's A-chain to its B-chain in the proinsulin molecule. In the context of diabetes or hypoglycemia, a measurement of C-peptide blood serum levels can be used to distinguish between different conditions with similar clinical features.

In the insulin synthesis pathway, first preproinsulin is translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum of beta cells of the pancreas with an A-chain, a C-peptide, a B-chain, and a signal sequence. The signal sequence is cleaved from the N-terminus of the peptide by a signal peptidase, leaving proinsulin. After proinsulin is packaged into vesicles in the Golgi apparatus (beta-granules), the C-peptide is removed, leaving the A-chain and B-chain bound together by disulfide bonds, that constitute the insulin molecule.

History

[edit]Proinsulin C-peptide was first described in 1967 in connection with the discovery of the insulin biosynthesis pathway.[2] Isolation of bovin C-peptide, determination of sequence, preparation of human C-peptide were done in 1971.[3] C-peptide serves as a linker between the A- and the B- chains of insulin and facilitates the efficient assembly, folding, and processing of insulin in the endoplasmic reticulum. Equimolar amounts of C-peptide and insulin are then stored in secretory granules of the pancreatic beta cells and both are eventually released to the portal circulation. Initially, the sole interest in C-peptide was as a marker of insulin secretion and has, as such, been of great value in furthering the understanding of the pathophysiology of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The first documented use of the C-peptide test was in 1972.[4] In the first decade of 21st century, C-peptide has been found to be a bioactive peptide in its own right, with effects on microvascular blood flow and tissue health.[5]

Function

[edit]Cellular effects of C-peptide

[edit]C-peptide has been shown to bind to the surface of a number of cell types such as neuronal, endothelial, fibroblast and renal tubular, at nanomolar concentrations to a receptor that is likely G-protein-coupled. The signal activates Ca2+-dependent intracellular signaling pathways such as MAPK, PLCγ, and PKC, leading to upregulation of a range of transcription factors as well as eNOS and Na+K+ATPase activities.[6] The latter two enzymes are known to have reduced activities in patients with type I diabetes and have been implicated in the development of long-term complications of type I diabetes such as peripheral and autonomic neuropathy.

In vivo studies in animal models of type 1 diabetes have established that C-peptide administration results in significant improvements in nerve and kidney function. Thus, in animals with early signs of diabetes-induced neuropathy, C peptide treatment in replacement dosage results in improved peripheral nerve function, as evidenced by increased nerve conduction velocity, increased nerve Na+,K+ ATPase activity, and significant amelioration of nerve structural changes.[7] Likewise, C-peptide administration in animals that had C-peptide deficiency (type 1 model) with nephropathy improves renal function and structure; it decreases urinary albumin excretion and prevents or decreases diabetes-induced glomerular changes secondary to mesangial matrix expansion.[8][9][10][11] C-peptide also has been reported to have anti-inflammatory effects as well as aid repair of smooth muscle cells.[12][13] A recent epidemiologic study suggests a U-shaped relationship between C-peptide levels and risk of cardiovascular disease.[14]

Clinical uses of C-peptide testing

[edit]Patients with diabetes may have their C-peptide levels measured as a means of distinguishing type 1 diabetes from type 2 diabetes or maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY).[15] Measuring C-peptide can help to determine how much of their own natural insulin a person is producing as C-peptide is secreted in equimolar amounts to insulin. C-peptide levels are measured instead of insulin levels because C-peptide can assess a person's own insulin secretion even if they receive insulin injections, and because the liver metabolizes a large and variable amount of insulin secreted into the portal vein but does not metabolise C-peptide, meaning blood C-peptide may be a better measure of portal insulin secretion than insulin itself.[16][17] A very low C-peptide confirms Type 1 diabetes and insulin dependence and is associated with high glucose variability, hyperglycaemia and increased complications. The test may be less sufficient to diagnose or recognize a subgroup of type 1 diabetes named Latent autoimmune diabetes in adults (LADA), whose C-peptide levels may not be as low as those in typical Type 1 diabetes while may sometimes overlap with those seen in type 2 diabetes, and Beta-cell antibody testing is needed for better diagnosis in this case.[18][19]

C-peptide can be used for differential diagnosis of hypoglycemia. The test may be used to help determine the cause of hypoglycaemia (low glucose), values will be low if a person has taken an overdose of insulin but not suppressed if hypoglycaemia is due to an insulinoma or sulphonylureas.

Factitious (or factitial) hypoglycemia may occur secondary to the surreptitious use of insulin. Measuring C-peptide levels will help differentiate a healthy patient from a diabetic one.

C-peptide may be used for determining the possibility of gastrinomas associated with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasm syndromes (MEN 1). Since a significant number of gastrinomas are associated with MEN involving other hormone producing organs (pancreas, parathyroids, and pituitary), higher levels of C-peptide together with the presence of a gastrinoma suggest that organs besides the stomach may harbor neoplasms.

C-peptide levels may be checked in women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS) to help determine degree of insulin resistance.

Ultrasensitive C-peptide assays have made it possible to detect very low levels of circulating C-peptide even in patients with longstanding type-1 diabetes.[20] Studies have demonstrated that the presence of residual C-peptide in longstanding type-1 diabetes is associated with a lower risk for developing microvascular complications and a significant reduction in incidence of severe hypoglycaemia.[21]

Therapeutics

[edit]Therapeutic use of C-peptide has been explored in small clinical trials in diabetic kidney disease.[22][23] Creative Peptides,[24] Eli Lilly,[25] and Cebix[26] all had drug development programs for a C-peptide product. Cebix had the only ongoing program until it completed a Phase IIb trial in December 2014 that showed no difference between C-peptide and placebo, and it terminated its program and went out of business.[27][28]

References

[edit]- ^ C-Peptide - Compound Summary Archived October 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, PubChem.

- ^ Steiner DF, Cunningham D, Spigelman L, Aten B (August 1967). "Insulin biosynthesis: evidence for a precursor". Science. 157 (3789): 697–700. Bibcode:1967Sci...157..697S. doi:10.1126/science.157.3789.697. PMID 4291105. S2CID 29382220.

- ^ Brandenburg D (2008). "History and Diagnostic Significance of C-Peptide". Experimental Diabetes Research. 2008: 576862. doi:10.1155/2008/576862. ISSN 1687-5214. PMC 2396242. PMID 18509495.

- ^ Brandenburg D (2008). "History and diagnostic significance of C-peptide". Exp Diabetes Res. 2008: 576862. doi:10.1155/2008/576862. PMC 2396242. PMID 18509495.

- ^ Forst T, Weber MM, Kunt T, Pfützner A (2012). "Role of C-Peptide in the Regulation of Microvascular Blood Flow". Diabetes & C-Peptide. pp. 45–54. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-391-2_5. ISBN 978-1-61779-390-5. Archived from the original on March 16, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ Hills CE, Brunskill NJ (2008). "Intracellular signalling by C-peptide". Experimental Diabetes Research. 2008: 635158. doi:10.1155/2008/635158. PMC 2276616. PMID 18382618.

- ^ Sima AA, Zhang W, Sugimoto K, Henry D, Li Z, Wahren J, Grunberger G (July 2001). "C-peptide prevents and improves chronic Type I diabetic polyneuropathy in the BB/Wor rat". Diabetologia. 44 (7): 889–97. doi:10.1007/s001250100570. PMID 11508275.

- ^ Samnegård B, Jacobson SH, Jaremko G, Johansson BL, Sjöquist M (October 2001). "Effects of C-peptide on glomerular and renal size and renal function in diabetic rats". Kidney International. 60 (4): 1258–65. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00964.x. PMID 11576340.

- ^ Samnegård B, Jacobson SH, Jaremko G, Johansson BL, Ekberg K, Isaksson B, et al. (March 2005). "C-peptide prevents glomerular hypertrophy and mesangial matrix expansion in diabetic rats". Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation. 20 (3): 532–8. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfh683. PMID 15665028.

- ^ Nordquist L, Brown R, Fasching A, Persson P, Palm F (November 2009). "Proinsulin C-peptide reduces diabetes-induced glomerular hyperfiltration via efferent arteriole dilation and inhibition of tubular sodium reabsorption". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 297 (5): F1265-72. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00228.2009. PMC 2781335. PMID 19741019.

- ^ Nordquist L, Wahren J (2009). "C-Peptide: the missing link in diabetic nephropathy?". The Review of Diabetic Studies. 6 (3): 203–10. doi:10.1900/RDS.2009.6.203 (inactive April 24, 2024). PMC 2827272. PMID 20039009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of April 2024 (link) - ^ Luppi P, Cifarelli V, Tse H, Piganelli J, Trucco M (August 2008). "Human C-peptide antagonises high glucose-induced endothelial dysfunction through the nuclear factor-kappaB pathway". Diabetologia. 51 (8): 1534–43. doi:10.1007/s00125-008-1032-x. PMID 18493738.

- ^ Mughal RS, Scragg JL, Lister P, Warburton P, Riches K, O'Regan DJ, et al. (August 2010). "Cellular mechanisms by which proinsulin C-peptide prevents insulin-induced neointima formation in human saphenous vein". Diabetologia. 53 (8): 1761–71. doi:10.1007/s00125-010-1736-6. PMC 2892072. PMID 20461358.

- ^ Koska J, Nuyujukian DS, Bahn G, Zhou JJ, Reaven PD (2021). "Association of low fasting C-peptide levels with cardiovascular risk, visit-to-visit glucose variation and severe hypoglycemia in the Veterans Affairs Diabetes Trial (VADT)". Cardiovascular Diabetology. 20 (1): 232. doi:10.1186/s12933-021-01418-z. PMC 8656002. PMID 34879878.

- ^ Jones AG, Hattersley AT (July 2013). "The clinical utility of C-peptide measurement in the care of patients with diabetes". Diabetic Medicine. 30 (7): 803–17. doi:10.1111/dme.12159. PMC 3748788. PMID 23413806.

- ^ Clark PM (September 1999). "Assays for insulin, proinsulin(s) and C-peptide". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 36 (5): 541–64. doi:10.1177/000456329903600501. PMID 10505204. S2CID 32483378.

- ^ Shapiro ET, Tillil H, Rubenstein AH, Polonsky KS (November 1988). "Peripheral insulin parallels changes in insulin secretion more closely than C-peptide after bolus intravenous glucose administration". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 67 (5): 1094–9. doi:10.1210/jcem-67-5-1094. PMID 3053748.

- ^ R C, Udayabhaskaran V, Binoy J Paul, K.P Ramamoorthy (July 2013). "A study of non-obese diabetes mellitus in adults in a tertiary care hospital in Kerala, India". International Journal of Diabetes in Developing Countries. 33 (2): 83–85. doi:10.1007/s13410-013-0113-7. S2CID 71767996.

- ^ O'Neal KS, Johnson JL, Panak RL (November 1, 2016). "Recognizing and Appropriately Treating Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults". Diabetes Spectrum. 29 (4): 249–252. doi:10.2337/ds15-0047. PMC 5111528. PMID 27899877. Archived from the original on March 15, 2024. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ Keenan HA, Sun JK, Levine J, Doria A, Aiello LP, Eisenbarth G, Bonner-Weir S, King GL (August 10, 2010). "Residual Insulin Production and Pancreatic β-Cell Turnover After 50 Years of Diabetes: Joslin Medalist Study". Diabetes. 59 (11): 2846–2853. doi:10.2337/db10-0676. ISSN 0012-1797. PMC 2963543. PMID 20699420. Archived from the original on March 16, 2024. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ Jeyam A, Colhoun H, McGurnaghan S, Blackbourn L, McDonald TJ, Palmer CN, McKnight JA, Strachan MW, Patrick AW, Chalmers J, Lindsay RS, Petrie JR, Thekkepat S, Collier A, MacRury S (February 5, 2021). "Erratum. Clinical Impact of Residual C-Peptide Secretion in Type 1 Diabetes on Glycemia and Microvascular Complications. Diabetes Care 2021;44:390–398". Diabetes Care: dc21er04b. doi:10.2337/dc21er04b. ISSN 0149-5992. PMID 33547206. S2CID 237216616. Archived from the original on March 16, 2024. Retrieved June 8, 2023.

- ^ Brunskill NJ (January 2017). "C-peptide and diabetic kidney disease". Journal of Internal Medicine. 281 (1): 41–51. doi:10.1111/joim.12548. PMID 27640884.

- ^ Shaw JA, Shetty P, Burns KD, Fergusson D, Knoll GA (2015). "C-peptide as a Therapy for Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 10 (5): e0127439. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1027439S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127439. PMC 4439165. PMID 25993479.

- ^ "C-peptide - Creative Peptides -". AdisInsight. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ "C-peptide - Eli Lilly". AdisInsight. Archived from the original on September 12, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ "C-peptide long-acting - Cebix". adisinsight.springer.com. AdisInsight. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ Bigelow BV (February 23, 2015). "Cebix Shuts Down Following Mid-Stage Trial of C-Peptide Drug". Xconomy. Archived from the original on December 28, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ Garde D (February 24, 2015). "Cebix hangs it up after raising $50M for diabetes drug". FierceBiotech. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

External links

[edit] Media related to C-peptide at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to C-peptide at Wikimedia Commons