Sacred geometry

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2023) |

Sacred geometry ascribes symbolic and sacred meanings to certain geometric shapes and certain geometric proportions.[1] It is associated with the belief of a divine creator of the universal geometer. The geometry used in the design and construction of religious structures such as churches, temples, mosques, religious monuments, altars, and tabernacles has sometimes been considered sacred. The concept applies also to sacred spaces such as temenoi, sacred groves, village greens, pagodas and holy wells, Mandala Gardens and the creation of religious and spiritual art.

As worldview and cosmology

[edit]The belief that a god created the universe according to a geometric plan has ancient origins. Plutarch attributed the belief to Plato, writing that "Plato said God geometrizes continually" (Convivialium disputationum, liber 8,2). In modern times, the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss adapted this quote, saying "God arithmetizes".[2]

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) believed in the geometric underpinnings of the cosmos.[3] Harvard mathematician Shing-Tung Yau expressed a belief in the centrality of geometry in 2010: "Lest one conclude that geometry is little more than a well-calibrated ruler – and this is no knock against the ruler, which happens to be a technology I admire – geometry is one of the main avenues available to us for probing the universe. Physics and cosmology have been, almost by definition, absolutely crucial for making sense of the universe. Geometry's role in this may be less obvious, but is equally vital. I would go so far as to say that geometry not only deserves a place at the table alongside physics and cosmology, but in many ways, it is the table."[4]

Natural forms

[edit]

According to Stephen Skinner, the study of sacred geometry has its roots in the study of nature, and the mathematical principles at work therein.[5] Many forms observed in nature can be related to geometry; for example, the chambered nautilus grows at a constant rate and so its shell forms a logarithmic spiral to accommodate that growth without changing shape. Also, honeybees construct hexagonal cells to hold their honey. These and other correspondences are sometimes interpreted in terms of sacred geometry and considered to be further proof of the natural significance of geometric forms.

Representations in Art and architecture

[edit]Geometric ratios, and geometric figures were often employed in the designs of ancient Egyptian, ancient Indian, Greek and Roman architecture. Medieval European cathedrals also incorporated symbolic geometry. Indian and Himalayan spiritual communities often constructed temples and fortifications on design plans of mandala and yantra. Mandala Vaatikas or Sacred Gardens were designed using the same principles.

Many of the sacred geometry principles of the human body and of ancient architecture were compiled into the Vitruvian Man drawing by Leonardo da Vinci. The latter drawing was itself based on the much older writings of the Roman architect Vitruvius.

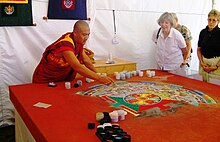

In Buddhism

[edit]

Mandalas are made up of a compilation of geometric shapes. In Buddhism, it is made up of concentric circles and squares that are equally placed from the center. Located within the geometric configurations are deities or suggestions of the deity, such as in the form of a symbol.[6] This is because Buddhists believe that deities can actually manifest inside the mandala.[7] Mandalas can be created with a variety of mediums. Tibetan Buddhists create mandalas out of sand that are then ritually destroyed. In order to create the mandala, two lines are first drawn on a predetermined grid.[6] The lines, known as Brahman lines, must overlap at the precisely calculated center of the grid. The mandala is then divided into thirteen equal parts not by a mathematical calculation, but through trial and error.[7] Next, monks purify the grid to prepare it for the constructing of the deities before sand is finally added. Tibetan Buddhists believe that anyone who looks at the mandala will receive positive energy and be blessed. Due to the Buddhist belief in impermanence, the mandala is eventually dismantled and is ritualistically released into the world.[7]

In Chinese spiritual traditions

[edit]One of the cornerstones of Chinese folk religion is the relationship between man and nature. This is epitomized in feng shui, which are architectural principles outlining the design plans of buildings in order to optimize the harmony of man and nature through the movement of Chi, or “life-generating energy.” [8] In order to maximize the flow of Chi throughout a building, its design plan must utilize specific shapes. Rectangles and squares are considered to be the best shapes to use in feng shui design. This is because other shapes may obstruct the flow of Chi from one room to the next due to what are considered to be unnatural angles.[8] Room layout is also an important element, as doors should be proportional to one another and located at appropriate positions throughout the house. Typically, doors are not situated across from one another because it may cause Chi to flow too fast from one room to the next.[8]

The Forbidden City is an example of a building that uses sacred geometry through the principles of feng shui in its design plan. It is laid out in the shape of a rectangle that measures over half a mile long and about half a mile wide.[9] Furthermore, the Forbidden City constructed its most important buildings on a central axis. The Hall of Supreme Harmony, which was the Emperor’s throne room, is located at the midpoint or “epicenter” of the central axis. This was done intentionally, as it was meant to show that when the Emperor entered this room, he would be ceremonially transformed into the center of the universe.[9]

In Islam

[edit]The geometric designs in Islamic art are often built on combinations of repeated squares and circles, which may be overlapped and interlaced, as can arabesques (with which they are often combined), to form intricate and complex patterns, including a wide variety of tessellations. These may constitute the entire decoration, may form a framework for floral or calligraphic embellishments, or may retreat into the background around other motifs. The complexity and variety of patterns used evolved from simple stars and lozenges in the ninth century, through a variety of 6- to 13-point patterns by the 13th century, and finally to include also 14- and 16-point stars in the sixteenth century.

Geometric patterns occur in a variety of forms in Islamic art and architecture including kilim carpets, Persian girih and Moroccan/Algerian zellige tilework, muqarnas decorative vaulting, jali pierced stone screens, ceramics, leather, stained glass, woodwork, and metalwork.

Islamic geometric patterns are used in the Quran, Mosques and even in the calligraphies.

In Hinduism/ Indic Religion

[edit]

The Agamas are a collection of Sanskrit,[10] Tamil, and Grantha[11] scriptures chiefly constituting the methods of temple construction and creation of idols, worship means of deities, philosophical doctrines, meditative practices, attainment of sixfold desires, and four kinds of yoga.[10]

Elaborate rules are laid out in the Agamas for Shilpa (the art of sculpture) describing the quality requirements of such matters as the places where temples are to be built, the kinds of image to be installed, the materials from which they are to be made, their dimensions, proportions, air circulation, and lighting in the temple complex. The Manasara and Silpasara are works that deal with these rules. The rituals of daily worship at the temple also follow rules laid out in the Agamas.

Hindu temples, the symbolic representation of cosmic model is then projected onto Hindu temples using the Vastu Shastra principle of Sukha Darshan, which states that smaller parts of the temple should be self-similar and a replica of the whole. The repetition of these replication parts symbolizes the natural phenomena of fractal patterns found in nature. These patterns make up the exterior of Hindu temples. Each element and detail are proportional to each other, this occurrence is also known as the sacred geometry.[12]

In Christianity

[edit]The construction of Medieval European cathedrals was often based on geometries intended to make the viewer see the world through mathematics, and through this understanding, gain a better understanding of the divine.[13] These churches frequently featured a Latin Cross floor-plan.[14]

At the beginning of the Renaissance in Europe, views shifted to favor simple and regular geometries. The circle in particular became a central and symbolic shape for the base of buildings, as it represented the perfection of nature and the centrality of man's place in the universe.[14] The use of the circle and other simple and symmetrical geometric shapes was solidified as a staple of Renaissance sacred architecture in Leon Battista Alberti's architectural treatise, which described the ideal church in terms of spiritual geometry.[15]

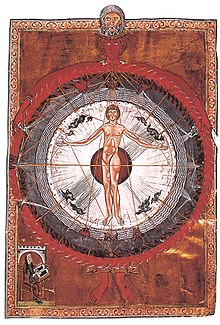

In the High Middle Ages, leading Christian philosophers explained the layout of the universe in terms of a microcosm analogy. In her book describing the divine visions she witnessed, Hildegard of Bingen explains that she saw an outstretched human figure located within a circular orb.[16] When interpreted by theologians, the human figure was Christ and mankind showing the Earthly realm and the circumference of the circle was a representation of the universe. Some images also show above the universe a depiction of God.[16] This is thought to later have inspired Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man.

Dante uses circles to make up the nine layers of hell categorized in his book, The Divine Comedy. “Celestial spheres” are also utilized to make up the nine layers of Paradise.[17] He further creates a cosmic order of circular forms that stretches from Jerusalem in the Earthly realm up to God in Heaven.[17] This cosmology is believed to have been inspired by the ancient astronomer Ptolemy.[17]

Unanchored geometry

[edit]Stephen Skinner criticizes the tendency of some writers to place a geometric diagram over virtually any image of a natural object or human created structure, find some lines intersecting the image and declare it based on sacred geometry. If the geometric diagram does not intersect major physical points in the image, the result is what Skinner calls "unanchored geometry".[18]

Notable artists

[edit]See also

[edit]- Circle dance

- Golden Ratio

- Harmony of the spheres

- Lu Ban and Feng shui

- Magic circle

- Numerology

- Shield of the Trinity

- 108 (number)

References

[edit]- ^ "Polygons, Tilings, & Sacred Geometry". Archived from the original on February 7, 2005.

- ^ Cathérine Goldstein, Norbert Schappacher, Joachim Schwermer, The shaping of arithmetic, p. 235.

- ^ Calter, Paul (1998). "Celestial Themes in Art & Architecture". Dartmouth College. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ Shing-Tung Yau and Steve Nadis, The Shape of Inner Space, (New York: Basic Books, 2010), 18.

- ^ Skinner, Stephen (2009). Sacred Geometry: Deciphering the Code. Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-6582-7.

- ^ a b Brauen, Martin; Rubin Museum of Art (2009). The mandala in Tibetan Buddhism from the book Mandala: Sacred circle in Tibetan Buddhism (Rev. and updated.). New York, N.Y.: Rubin Museum of Art. p. 11.

- ^ a b c Sahney, Puja (2006). "In the midst of a monastery: Filming the making of a Buddhist sand mandala". Voices (New York Folklore Society). 32 (1–2): 23 – via Proquest.

- ^ a b c Çeliker, Afet; Çavuşoğlu, Banu Tevfikler; Öngül, Zehra (2014). "Comparative study of courtyard housing using feng shui". Open House International. 39 (1): 41. doi:10.1108/OHI-01-2014-B0005.

- ^ a b Walker, Veronica (2022). "The Forbidden City: Center of an imperial world". National Geographic. Vol. 8, no. 4. p. 60.

- ^ a b Grimes, John A. (1996). A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English. State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791430682. LCCN 96012383. [1]

- ^ Nagalingam, Pathmarajah (2009). The Religion of the Agamas. Siddhanta Publications. [2]

- ^ "Sacred Geometry Of Hindu Temples". Indic Today. 2019-10-22. Retrieved 2021-04-14.

- ^ Petersen, Toni (2003), "A(rt and) A(rchitecture) T(hesaurus)", Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t000037, ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4

- ^ a b CUMMINGS, L.A. (1986), "A RECURRING GEOMETRICAL PATTERN IN THE EARLY RENAISSANCE IMAGINATION", Symmetry, Elsevier, pp. 981–997, doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-033986-3.50067-7, ISBN 9780080339863

- ^ Rudolf., Wittkower (1998). Architectural principles in the age of humanism. Academy Editions. ISBN 978-0471977636. OCLC 981109542.

- ^ a b Lester, Toby (2012). Da Vinci's Ghost: Genius, Obsession, and How Leonardo Created the World in his Own Image. New York: Free Press. p. 50.

- ^ a b c Pagano, Alessandra; Dalena, Matteo (2022). "Dante: 700 years of the Inferno". National Geographic. Vol. 8, no. 4. p. 40.

- ^ Skinner, Stephen (2006). Stephen Skinner, Sacred geometry: deciphering the code, p91. Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 9781402741296.

Further reading

[edit]- Bain, George. Celtic Art: The Methods of Construction. Dover, 1973. ISBN 0-486-22923-8.

- Bromwell, Henry P. H. (2010). Townley, Kevin (ed.). Restorations of Masonic Geometry and Symbolry: Being a Dissertation on the Lost Knowledges of the Lodge. Lovers of the Craft. ISBN 978-0-9713441-5-0. Archived from the original on 2012-02-03. Retrieved Jan 7, 2012.

- Bamford, Christopher, Homage to Pythagoras: Rediscovering Sacred Science, Lindisfarne Press, 1994, ISBN 0-940262-63-0

- Critchlow, Keith (1970). Order In Space: A Design Source Book. New York: Viking.

- Critchlow, Keith (1976). Islamic Patterns: An Analytical and Cosmological Approach. Schocken Books. ISBN 978-0-8052-3627-9.

- Iamblichus; Robin Waterfield; Keith Critchlow; Translated by Robin Waterfield (1988). The Theology of Arithmetic: On the Mystical, Mathematical and Cosmological Symbolism of the First Ten Numbers. Phanes Press. ISBN 978-0-933999-72-5.

- Johnson, Anthony: Solving Stonehenge, the New Key to an Ancient Enigma. Thames & Hudson 2008 ISBN 978-0-500-05155-9

- Lesser, George (1957–64). Gothic cathedrals and sacred geometry. London: A. Tiranti.

- Lawlor, Robert. Sacred Geometry: Philosophy and practice (Art and Imagination). Thames & Hudson, 1989 (1st edition 1979, 1980, or 1982). ISBN 0-500-81030-3.

- Lippard, Lucy R. Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory. Pantheon Books New York 1983 ISBN 0-394-51812-8

- Mann, A. T. Sacred Architecture, Element Books, 1993, ISBN 1-84333-355-4.

- Michell, John. City of Revelation. Abacus, 1972. ISBN 0-349-12320-9.

- Schneider, Michael S. A Beginner's Guide to Constructing the Universe: Mathematical Archetypes of Nature, Art, and Science. Harper, 1995. ISBN 0-06-092671-6

- Steiner, Rudolf; Creeger, Catherine (2001). The Fourth Dimension : Sacred Geometry, Alchemy, and Mathematics. Anthroposophic Press. ISBN 978-0-88010-472-2.

- The Golden Mean, Parabola magazine, v.16, n.4 (1991)

- West, John Anthony, Inaugural Lines: Sacred geometry at St. John the Divine, Parabola magazine, v.8, n.1, Spring 1983.