National Rebirth of Poland

This article needs to be updated. (October 2018) |

National Rebirth of Poland Narodowe Odrodzenie Polski | |

|---|---|

| Chairman | Adam Gmurczyk |

| Founded | 10 November 1981 |

| Headquarters | ul. Kredytowa 6/22 00-062 Warsaw |

| Ideology | Nationalradicalism Ultranationalism Polish nationalism National syndicalism Anti-globalism Hard Euroscepticism Anti-Americanism Anti-capitalism Anti-Zionism[1] Third Position Corporatism[2] Distributism[2] Radical environmentalism[3] Anti-communism[4] Neo-fascism |

| Political position | Far-right[5][6] |

| International affiliation | International Third Position[5][7] |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www.nop.org.pl en.nop.org.pl | |

| Part of a series on |

| Neo-fascism |

|---|

|

|

|

National Rebirth of Poland (Polish: Narodowe Odrodzenie Polski), abbreviated to NOP, is an ultranationalist far-right political party in Poland registered by the District Court in Warsaw and National Electoral Commission. As of the 2015 election, the party had no seats in the Polish parliament. It was a member of the European National Front.

History and politics

[edit]

National Rebirth of Poland was founded as a nationalist discussion group for young people on 10 November 1981.[8] It joined the Christian National Union when that party was founded in 1989, before leaving in February 1990.[9] The NOP registered as a political party in 1992. The party is the only far-right organisation to claim to be a successor to the National Radical Camp Falanga (ONR),[10] the pre-war nationalist youth organisation, which was banned in 1934.[11][12]

NOP publishes the magazines Szczerbiec (the name of the Polish royal coronation sword), which lists neofascists Derek Holland and Roberto Fiore among the members of its editorial board,[11] Młodzież Narodowa (National Youth), Myśl (The Thought), and 17 – Cywilizacja Czasów Próby (17 – The Civilization of the Times of Trial).

In 2009, NOP membership in Poland was estimated at 1000. NOP also has supporters outside Poland, notably among the Polish American community, including Polish Patriots’ Association residing in New York City, and the revisionist Polish Historical Institute in Chicago.[13]

In 2001, the NOP tried to enter parliamentary politics for the first time. The newly created NOP front organization, the New Forces Alliance (Sojusz Nowych Sił), joined the nationalist electoral bloc, Alternative Social Movement (Alternatywa Ruch Społeczny). Among the NOP candidates were Marcin Radzewicz, the leader of the openly neo-Nazi National Socialist Front (Front Narodowo-Socjalistyczny). ARS gained just below 0.5% of the votes, and the alliance was dissolved.[14]

In the 2005 parliamentary elections, the NOP received 0.06% of the vote.[15] In the 2006 self-government regional elections, it received 0.30%, or about 41 000 votes. In the 2007 parliamentary election, the NOP received 42 407 votes in four electoral districts. In the self-government regional elections in 2010, the party received 0.24% of the vote.

In the 2011 parliamentary elections, NOP senate candidate Anetta Stemler, running in the 1st electoral district, received 2934 votes, or 3.10%.

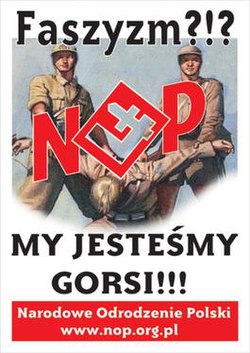

The NOP is known for trying to get media attention with its shock value campaigns.[16] During the 2007 parliamentary election, the NOP distributed election campaign posters with the slogan "Fascism? We are worse."[16]

Another, openly homophobic shock value campaign conducted by the NOP was called Zakaz Pedalowania (the phrase is a pun meaning both "Cycling Forbidden" and "Faggotry Forbidden").[17] On 17 May 2006 in Toruń, the NOP organized a counter-demonstration against a public LGBT rights supporters' meeting. NOP members chanted slogans, including "gas the queers" (pedały do gazu) and "there will be a baton for a queer face" (znajdzie się kij na pedalski ryj).[18][19]

Antisemitism and racism

[edit]The NOP is stated to be an antisemitic organisation by a number of government bodies, nongovernmental organizations, academic institutions and individual experts worldwide, such as the United States Department of State,[20][21] and the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI).[22] According to The Stephen Roth Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism and Racism, the NOP is promoting violent forms of neo-fascism and antisemitism, including Holocaust denial.[23] According to the British historian, Dr John Pollard, neo-Nazi elements in the NOP and their racism and homophobia continue to give rise to concern in other member countries of the European Union.[24] NOP actions were also condemned by the Anti-Defamation League, which claims that the NOP is an openly anti-Semitic extremist organization.[25] According to the magazine The Warsaw voice, the manifesto of the National Revival of Poland, which contains a sentence stating that "Jews will be removed from Poland, and their possessions will be confiscated", is taken directly from Adolf Hitler's Mein Kampf.[26] The magazine also claims that the official greeting gesture used in the party is the Nazi-like gesture of the raised arm.[26]

A number of NOP-related incidents received some media coverage in Poland and abroad. According to the European Roma Rights Centre, on July 3, 1998, NOP supporters vandalised the Roma community centre in Łódź. Along with racist graffiti, swastikas were sprayed onto the office walls. The perpetrators also left behind their signature as NOP – Narodowe Odrodzenie Polski. During the same night, the same group reportedly vandalised the premises of the Jehovah's Witnesses religious group.[27]

In March 2000, in Łódź, swastikas and the slogan "Jews out!" along with NOP symbols were spray-painted on the home of Marek Edelman, who was the deputy commander in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising and the last of the leaders of the uprising still alive. The incident was condemned by the president and prime minister of Poland, who sent Edelman letters of support and apology.[28]

NOP front organization National-Radical Institute (Instytut Narodowo-Radykalny, INR) was involved in publishing Western and Polish Holocaust denial literature. In 1997, INR published a volume of translated works of Western Holocaust deniers under the title The Myth of the Holocaust.[11] The same year, INR announced that there were no exterminations in gas chambers at Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.[11][29]

In 2006, the NOP was involved in campaigning to free convicted British Holocaust denier David Irving from prison in Austria, and produced a poster containing the slogan "David Irving – Uwolnić prawdę" ("David Irving – Free the truth".[30])

The party also expressed support for the bombing of Israel at the time of the 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict, with a poster image stating, "Bomby na Izrael – Już czas!!!" ("Bombs against Israel – it's about time!!!").[1] On August 13, 2006, NOP leader Adam Gmurczyk published a declaration on behalf of the NOP Executive Council titled Izrael musi zostać zniszczony! (Israel must be destroyed!), calling for the international military takeover of Israel, and offering to put administrative control of Jerusalem in the hands of Pope Benedict XVI and his successors.[31]

On April 14, 2007, in Kraków, antisemitic slogans were shouted and fascist-like gestures made by the participants of an NOP demonstration. Investigations by the Public Prosecutor's Office were discontinued on November 26, 2007, as no perpetrators were identified and the case was not classified as an offense.[32]

Election results

[edit]Elections

[edit]In 2001, the NOP tried to enter parliamentary politics for the first time. The newly created NOP front organization, the New Forces Alliance (Sojusz Nowych Sił), joined the nationalist electoral bloc, Alternative Social Movement (Alternatywa Ruch Społeczny). Among the NOP candidates were Marcin Radzewicz, the leader of the openly neo-Nazi National Socialist Front (Front Narodowo-Socjalistyczny). ARS gained just below 0.5% of the votes, and the alliance was dissolved.

In the 2005 parliamentary elections, the NOP received 0.06% of the vote. In the 2006 self-government regional elections, it received 0.30%, or about 41 000 votes. In the 2007 parliamentary election, the NOP received 42 407 votes in four electoral districts. In the self-government regional elections in 2010, the party received 0.24% of the vote.

In the 2011 parliamentary elections, NOP senate candidate Anetta Stemler, running in the 1st electoral district, received 2934 votes, or 3.10%. She failed to win the Senate seat. After the 2011 parliamentary elections, NOP did not take part in any further elections; be it to Sejm, Senate or even local.

| Election year | # of votes |

% of vote |

# of overall seats won |

+/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 54,266 | 0.42 | 0 / 460

|

|

| 2005 | 7,376 | 0.06 | 0 / 460

|

|

| 2006 | 41,000 | 0.30 | 0 / 561

|

|

| 2007 | 42,407 | 0.30 | 0 / 460

|

|

| 2010 | ? | 0.24 | 0 / 561

|

|

| 2011 | 2,934 | 0.02 | 0 / 460

|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2006-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b "Warszawa: WYWIAD: Adam Gmurczyk – Narodowe Odrodzenie Polski!". drogalegionisty.pl. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- ^ "Warszawa: Nacjonaliści w obronie zieleni". www.nop.org.pl. Retrieved 2021-02-19.

- ^ "W hołdzie bohaterom – przeciwko komunizmowi i UE" [In tribute to heroes - against communism and the EU]. National Rebirth of Poland. 2014-12-16. Archived from the original on 2021-11-04.

- ^ a b Shafir, Michael (2012), "Denying the Shoah in Post-Communist Eastern Europe", Holocaust Denial: The Politics of Perfidy, de Gruyter, p. 36

- ^ Jakubowicz, Andrew (2007), "Notes for a Grave under Snow", Imaginary Neighbors: Mediating Polish-Jewish Relations After the Holocaust, University of Nebraska Press, p. 71

- ^ Pankowski, Rafal (2006), "Poland", World Fascism: A Historical Encyclopedia, vol. 1, ABC-CLIO, p. 523

- ^ Szajkowski, Bogdan (2004). Revolutionary and Dissident Movements of the World. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-9543811-2-7.

- ^ Berglund, Sten; Ekman, Joakim; Aarebrot, Frank H. (2004). The Handbook of Political Change in Eastern Europe. London: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-84064-854-6.

- ^ Borejsza et al (2006), p. 359

- ^ a b c d Michael Shafir Varieties of Antisemitism in Post-communist East Central Europe: Motivations and Political Discourse

- ^ Rafał Pankowski and Marcin Kornak. Poland. Racist Extremism in Central and Eastern Europe, Cas Mudde (Editor), pp. 156–183. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-35593-3

- ^ "Antisemitism and Racism". www.tau.ac.il. Archived from the original on April 4, 2008.

- ^ Cas Mudde (2005). Racist Extremism in Central and Eastern Europe. London: Routledge. p. 162. ISBN 0-415-35593-1. OCLC 55228719.

- ^ Elections 2005 on Gazeta Wyborcza website (en)

- ^ a b "Wiadomości z kraju i ze świata | Nasze Miasto".

- ^ « Zakaz Pedałowania » on NOP's website (pl)

- ^ http://lib.ohchr.org/HRBodies/UPR/Documents/Session1/PL/AI_POL_UPR_S1_2008anx_EUR%2001_017_2006.pdf United Nations Human Rights Council

- ^ http://amnesty.org.pl/archiwum/aktualnosci-strona-artykulu/article/4969/71/category/6/neste/1.html?cHash=adf146462f Archived 2008-10-01 at the Wayback Machine Amnesty International Polska

- ^ Country Reports on Human Rights Practices 2006, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor US State Dept.

- ^ International Religious Freedom Report 2007 US State Dept.

- ^ "European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) Third report on Poland Adopted on 17 December 2004" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- ^ Poland 2006 Archived 2008-05-20 at the Wayback Machine, by Stephen Roth Institute

- ^ John Pollard ‘Clerical Fascism’: Context, Overview and Conclusion in: Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions, Vol. 8, No. 2, p. 11, June 2007

- ^ Poland: Democracy and the Challenge of Extremism Archived 2008-10-01 at the Wayback Machine, by Anti-Defamation League, 2006

- ^ a b RACE: Fighting Fascism, Warsaw Voice, 31 July 2003

- ^ "Roma community center vandalised in Łódź, Poland". European Roma Rights Centre.

- ^ Anti-Semitic Incidents – March 2000, by the Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs

- ^ Kwiet, Konrad; Jürgen Matthäus (2004). Contemporary Responses to the Holocaust. Greenwood Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 0-275-97466-9.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-02-24. Retrieved 2006-08-12.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Narodowe Odrodzenie Polski (NOP) – Nacjonalistyczna Opozycja".

- ^ « Anti-Semitic Incidents In Poland », The Jewish Press, March 26, 2008

Further reading

[edit]- Rudnicki, Szymon (2006). Right-wing Radicalism in Contemporary Poland. Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 354–372. ISBN 978-1-57181-641-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

External links

[edit]- 1981 establishments in Poland

- Anti-Zionism in Poland

- Anti-Zionist political parties

- Anti-communist organisations in Poland

- Antisemitism in Europe

- Antisemitism in Poland

- Catholic political parties

- Catholicism and far-right politics

- Eurosceptic parties in Poland

- Right-wing antisemitism

- Far-right movements in Europe

- Far-right political parties in Poland

- Formerly banned far-right parties

- Fascism in Europe

- Neo-fascist parties

- Neo-Nazism in Poland

- National radicalism

- National syndicalism

- Nationalist parties in Poland

- Organizations that oppose LGBTQ rights in Poland

- Polish nationalist parties

- Political parties established in 1981

- Third Position