Chuck Norris

Chuck Norris | |

|---|---|

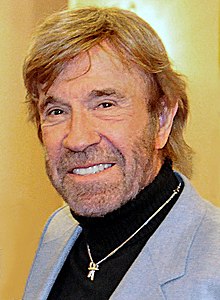

Norris in 2015 | |

| Born | Carlos Ray Norris March 10, 1940 Ryan, Oklahoma, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Martial artist, actor, screenwriter |

| Years active | 1968–present |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 5; including Mike and Eric |

| Relatives | Aaron Norris (brother) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1958–1962 |

| Rank | |

| Website | chucknorris |

| Signature | |

| |

Carlos Ray "Chuck" Norris (born March 10, 1940) is an American martial artist and actor. He is a black belt in Tang Soo Do, Brazilian jiu jitsu and judo.[1] After serving in the United States Air Force, Norris won many martial arts championships and later founded his own discipline, Chun Kuk Do. Shortly after, in Hollywood, Norris trained celebrities in martial arts. Norris went on to appear in a minor role in The Wrecking Crew (1968). Friend and fellow martial artist Bruce Lee invited him to play one of the main villains in The Way of the Dragon (1972). While Norris continued acting, friend and student Steve McQueen suggested he take it seriously. Norris took the starring role in the action film Breaker! Breaker! (1977), which turned a profit. His second lead, Good Guys Wear Black (1978), became a hit, and he soon became a popular action film star.

Norris went on to star in a streak of bankable independently made action and martial arts films, with A Force of One (1979), The Octagon (1980), and An Eye for an Eye (1981). This made Norris an international celebrity. He went on to make studio films like Silent Rage (1982) with Columbia, Forced Vengeance (1982) with MGM, and Lone Wolf McQuade (1983) with Orion. This led Cannon Films to sign Norris into a multiple film deal, starting with Missing in Action (1984), which proved to be very successful and launched a trilogy. Norris started to work almost exclusively on high-profile action films with Cannon, becoming its leading star during the 1980s. Films with Cannon include Invasion U.S.A (1985), The Delta Force (1986), and Firewalker (1986), among others. Apart from the Cannon films, Norris made Code of Silence (1985), which was received as one of his best films. In the 1990s, he played the title role in the long-running CBS television series Walker, Texas Ranger from 1993 until 2001. Until 2006, Norris continued taking lead roles in action movies, including Delta Force 2 (1990), The Hitman (1991), Sidekicks (1992), Forest Warrior (1996), and The President's Man (2000) and its sequel (2002). His last appearance in a major film release was in The Expendables 2 (2012).

Throughout his film and TV career, Norris diversified from his regular endeavors. He is a noted writer, having penned books on martial arts, exercise, philosophy, politics, Christianity, Western fiction, and biography. He was twice a New York Times bestselling author, first with his book on his personal philosophy of positive force and the psychology of self-improvement based on personal anecdotes called The Secret of Inner Strength: My Story (1988). His second New York Times bestseller, Black Belt Patriotism: How to Reawaken America (2008), is about his critique of current issues in the United States. Norris also appeared in several commercials endorsing several products, most notably being one of the main spokespersons for the Total Gym infomercials. In 2005, Norris found new fame on the Internet when Chuck Norris facts became an Internet meme documenting humorous, fictional, and often absurd feats of strength and endurance. Although Norris himself did not produce the "facts", he was hired to endorse many products that incorporated Chuck Norris facts in advertising. The phenomenon resulted in six books (two of them New York Times bestsellers), two video games, and several appearances on talk shows, such as Late Night with Conan O'Brien, in which he read the facts or participated in sketches.

Early life

Norris was born in Ryan, Oklahoma, on March 10, 1940,[2] to Wilma (née Scarberry) and Ray Dee Norris, who was a World War II Army soldier,[3] mechanic, bus driver, and a truck driver. Norris has stated that he has Irish and Cherokee roots.[3][4] Norris was named after Carlos Berry, his father's minister.[3] He was the oldest of three brothers, the younger two being Wieland and Aaron. Wieland Norris informed his eldest sibling he would not reach his 27th birthday; this prediction came true in 1970 when he was killed in the Vietnam War. When Norris was 16 years old, his parents divorced,[5] and he later relocated to Prairie Village, Kansas and then to Torrance, California with his mother and brothers.[4]

Norris has described his childhood as downbeat. He was nonathletic, shy, and scholastically mediocre.[6] His father, Ray, worked intermittently as an automobile mechanic, and went on drinking binges that lasted for months at a time. Embarrassed by his father's behavior and the family's financial plight, Norris developed a debilitating introversion that lasted for his entire childhood.[7]

Career

1958 to 1969: United States Air Force and martial arts breakthrough

Norris joined the United States Air Force as an Air Policeman (AP) in 1958 and was sent to Osan Air Base, South Korea. It was there that Norris acquired the nickname "Chuck" and began his training in Tang Soo Do (tangsudo), an interest that led to black belts in that art and the founding of the Chun Kuk Do ("Universal Way") form.[8] When he returned to the United States, he continued to serve as an AP at March Air Force Base in California.[9][10]

Norris was discharged from the Air Force in August 1962 with the rank of Airman first class. Following his military service, Norris applied to be a police officer in Torrance, California. While on the waiting list, Norris opened a martial arts studio.[11]

Norris started to participate in martial arts competitions. He was defeated in his first two tournaments, dropping decisions to Joe Lewis and Allen Steen. He lost three matches at the International Karate Championships to Tony Tulleners. By 1967, Norris had improved enough that he scored victories over the likes of Vic Moore. On June 3, Norris won the 1967 tournament of karate, Norris defeated seven opponents, until his final fight with Skipper Mullins.[12] On June 24, Norris was declared champion at the S. Henry Cho's All-American Karate Championship at the Madison Square Garden, taking the title from Julio LaSalle and defeating Joe Lewis.[13][14][15] During this time, Norris also worked for the Northrop Corporation and opened a chain of karate schools. Norris's official website lists celebrity clients at the schools; among them Steve McQueen, Chad McQueen, Bob Barker, Priscilla Presley, Donny Osmond and Marie Osmond.[16]

In early 1968, Norris suffered the tenth and final loss of his career, losing an upset decision to Louis Delgado. On November 24, 1968, he avenged his defeat to Delgado and by doing so won the Professional Middleweight Karate champion title, which he then held for six consecutive years.[5] On April 1, Norris successfully defended his All-American Karate Championship title, in a round-robin tournament, at the Karate tournament of champions of North America.[17] Again that year, Norris won for the second time the All-American Karate Championship. It was the last time Norris participated and retired undefeated.[18][19] While competing, Norris met Bruce Lee, who at the time was known for the TV series The Green Hornet. They developed a friendship, as well as a training and working relationship.

In 1969, during the first weekend of August, Norris defended his title as world champion at the International Karate Championship. The competition included champions from most of the fifty states as well as half a dozen from abroad who joined for the preliminaries.[20] Norris retained his title[21] and won Karate's triple crown for the most tournament wins of the year, he also got the Fighter of the Year award by Black Belt magazine. Around this time, Norris made his acting debut in the Matt Helm spy spoof The Wrecking Crew.

1970 to 1978: Early roles and breakthrough

In 1972, Norris acted as Bruce Lee's nemesis in the widely acclaimed martial arts movie Way of the Dragon (titled Return of the Dragon in its U.S. distribution). The film grossed over HK$5.3 million at the Hong Kong box office, beating previous records set by Lee's own films, The Big Boss and Fist of Fury, making it the highest-grossing film of 1972 in Hong Kong. The Way of the Dragon went on to gross an estimated US$130 million worldwide.[22] The film is credited with launching him toward stardom.

In 1973, Norris played a role in Jonathan Kaplan's The Student Teachers.[23]

In 1974, actor Steve McQueen, who was his martial art student and friend at the time, saw his potential and encouraged him to begin acting classes at MGM. That same year, he played the supporting role of the main antagonist in Lo Wei's Yellow Faced Tiger.[24] Norris plays a powerful drug king in San Francisco, where he dominates the criminal world including the police department. He is eventually challenged by a young police officer who stands up to corruption.[25] The film played theatrically in the United States in 1981 as Slaughter in San Francisco.[26] It was noticed that it was an older, low-budget film announcing Norris as the lead. The film played as a double-bill to other action and genre film. It was described as a low-budget martial arts actioner taking advantage of Norris's fame.[27][28][29]

In 1975, Norris wrote his first book Winning Tournament Karate on the practical study of competition training for any rank. It covers all phases of executing speedy attacks, conditioning, fighting form drills, and one-step sparring techniques.[30]

Norris's first starring role was 1977's Breaker! Breaker![31] He chose it after turning down offers to do several martial-arts films. Norris decided that he wanted to do films that had a story and where the action would take place when it is emotionally right. The low-budget film turned out to be very successful.[32]

In 1978, Norris starred in Good Guys Wear Black.[33] He considers it to be his first significant lead role. No studio wanted to release it, so Norris and his producers four-walled it, renting the theaters and taking whatever money came in.[34] The film did very well; shot on a $1 million budget, it made over $18 million at the box office.[35] Following years of kung fu film imports from Hong Kong action cinema during the 1970s, most notably Bruce Lee films followed by Bruceploitation flicks, Good Guys Wear Black launched Norris as the first successful homegrown American martial-arts star, having previously been best known as a villain in Lee's Way of the Dragon. Good Guys Wear Black distinguished itself from earlier martial-arts films by its distinctly American setting, characters, themes, and politics, a formula that Norris continued to develop with his later films.[36]

1979 to 1983: Action film star

In 1979, Norris starred in A Force of One, where he played Matt Logan, a world karate champion who assists the police in their investigation.[37] The film was developed while touring for Good Guys Wear Black. Again no studio wanted to pick it up, but it out-grossed the previous film by making $20 million at the box office.[34][38]

In 1980, he released The Octagon, where his character must stop a group of terrorists trained in the ninja style.[39] Unlike his previous films, this time the studios were interested. American Cinema Releasing distributed it and it made almost $19 million at the box office.[34][40]

In 1981, he starred in Steve Carver's An Eye for an Eye.[41]

In 1982, he had the lead in the action horror film Silent Rage.[42] It was his first film released by a major studio, Columbia Pictures.[43] Norris plays a sheriff who must stop a psychopath on a rampage. Shortly afterward MGM gave him a three-movie deal and that same year, they released Forced Vengeance (1982). Norris was unhappy with the direction they wanted to take with him, hence the contract was canceled.[34]

In 1983, Norris made Lone Wolf McQuade with Orion Pictures and Carver directing.[44] He plays a reckless but brave Texas Ranger who defeats an arms dealer played by David Carradine. The film was a worldwide hit and had a positive reception from movie critics, often being compared to Sergio Leone's stylish Spaghetti Westerns. The film became the inspiration for Norris's future hit TV show Walker, Texas Ranger. Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film a 3.5 star rating, calling the character of J.J. McQuade worthy of a film series and predicting the character would be a future classic, and it would be the first movie where Norris would wear his trademark beard.[45][46][47] The same year, he also published an exercise called Toughen Up! the Chuck Norris Fitness System.[48] Also in 1983, Xonox produced the video game Chuck Norris Superkicks for the Commodore 64, VIC-20, Atari 2600, and Colecovision. The game combines two types of gameplay: moving through a map, and fighting against enemies. The player takes control of Norris who has to liberate a hostage. It was later sold as Kung Fu Superkicks when the license for the use of the Chuck Norris name expired.

1984 to 1988: Mainstream success

In 1984, Norris starred in Joseph Zito's Missing in Action.[49] It's the first of a series of POW rescue fantasies, where he plays Colonel James Braddock. Produced by Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus and released under their Cannon Films banner, with which he had signed a multiple movie deal.[50] Norris later dedicated these films to his younger brother Wieland, who was a private in the 101st Airborne Division, and had been killed in June 1970 in Vietnam while on patrol in the defense of Firebase Ripcord.[51] The film was a huge success, and Norris became Cannon's most prominent star of the 1980s.

Missing in Action 2: The Beginning premiered on March 1, 1985.[52] It is a prequel to the first installment, about Braddock being held in a North Vietnamese POW camp.[53][54] Orion Pictures released Code of Silence on May 3.[55] It received positive reviews and was also a box-office success.[56][57][58][59] Code of Silence is a crime drama, and features Norris as a streetwise plainclothes officer who takes down a crime czar. Invasion U.S.A. premiered on September 27, with Zito directing.[60]

On February 14, 1986, Menahem Golan's The Delta Force premiered. Norris co-stars with Lee Marvin.[61] They play leaders of an elite squad of Special Forces troops who face a group of terrorists. The Delta Force was a box office success. In October, Ruby-Spears' cartoon Karate Kommandos first aired. The animated show lasted six episodes. In it, Norris voices a cartoon version of himself who leads a United States government team of operatives known as the Karate Kommandos. Marvel made a comic book adaptation.

On November 21, J. Lee Thompson's action-adventure comedy film Firewalker premiered, where Norris co-lead with Louis Gossett Jr.. Gossett and Norris play two seasoned treasure hunters whose adventures rarely result in any notable success.[62] Norris explained that the project came about when he wanted to show a lighter side of himself.[63] Gossett appreciated Norris efforts and said "I have great respect for what actors call stretch. Chuck had to open up first to allow this atmosphere. It has to do with his desire to stretch. Someone else could have been quite insecure. He chose to open up. He's studying hard and he's serious."[64] The review were mostly negative, while some thought it was a fine for a light action film.[65][66][67][68][69][70][71] Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times, enjoyed it of the cast he said they "really get into the light-hearted spirit of the occasion."[72] The film made $11,834,302 at the box-office.[73]

In 1987, he published the New York Times Best Seller The Secret of Inner Strength: My Story. It is about his self-improvement philosophy.[74]

On January 2, 1988, Braddock: Missing in Action III premiered, Norris returned to the title role and his brother Aaron Norris directed.[75] On August 28, Norris starred in Hero and the Terror directed by William Tannen.[76] In it Norris stars as a cop investigating a serial killer.[77]

1989 to 1999: Subsequent success

By 1990, his films had collectively grossed over $500 million worldwide . By this time, he had drawn comparisons to both Bruce Lee and Clint Eastwood, sometimes called the "blonde Bruce Lee" for his martial arts film roles while his "loner" persona was compared to the Eastwood character Dirty Harry.[78] That same year, MGM acquired the Cannon Films library. Norris continued making films with Aaron, who directed him in Delta Force 2,[79] The Hitman,[80] Sidekicks (1993),[81] Hellbound (1994), Top Dog (1995),[82] and Forest Warrior (1996).[83]

In 1993, he began shooting the action series Walker, Texas Ranger. The television show is centered on Sergeant Cordell Walker (Norris), a member of the Texas Rangers, a state-level bureau of investigation, and is about his adventures fighting criminals with his partner James Trivette. It lasted eight seasons on CBS and continued in syndication on other channels, notably the Hallmark Channel.[84] The show was very successful in the ratings throughout its run, ranking among the Top 30 programs from 1995 until 1999, and ranking in the Top 20 in both the 1995–1996 and 1998–1999 seasons. In 1999, Norris produced and played Walker in a supporting role in the Walker, Texas Ranger spin-off Sons of Thunder. The same year, also playing the role of Walker, Norris acted in a crossover episode of the Sammo Hung's TV show Martial Law. For another crossover, Hung also appeared as his character in Walker, Texas Ranger.

Separately from Walker, Texas Ranger, on August 25, 1993, the Randy Travis television special Wind in the Wire first aired. Norris was among the guests.[85] At the 1994 edition of the World Wrestling Federation (WWF)'s Survivor Series event, Norris was the special outside enforcer for the Casket Match between The Undertaker and Yokozuna.[86] During the match, Norris delivered a roundhouse kick to an interfering Jeff Jarrett.[87] In 1996, Norris wrote the book The Secret Power Within: Zen Solutions to Real Problems.[88] Since 1997, Norris has appeared with Christie Brinkley in a long-running series of cable TV infomercials promoting Total Gym home fitness equipment.[89] On November 1, 1998, CBS premiered Michael Preece's television film Logan's War: Bound by Honor, starring Norris and Eddie Cibrian.[90] The television film was ranked third among the thirteen most viewed shows of that week.[91]

2000 to 2005: Subsequent films and internet fame

In the early 2000s, Norris starred as a secret agent in the CBS television films The President's Man (2000) and The President's Man: A Line in the Sand.(2002).[92]

In 2003, Norris played a role in the supernatural Christian film Bells of Innocence.[93][additional citation(s) needed] That same year, he acted in one episode of the TV show Yes, Dear.[94]

In 2004, Rawson Marshall Thurber's comedy film DodgeBall: A True Underdog Story was released.[95] Norris plays himself as a judge during a dodgeball game. Described by critics as "a raunchy comedy that delivers for many", it grossed $167.7 million.[96]

That same year, he published his autobiography Against All Odds: My Story.

In 2005, Norris founded the World Combat League (WCL), a full-contact, team-based martial arts competition, of which part of the proceeds are given to his Kickstart Kids program.[97]

On October 17, 2005, CBS premiered the Sunday Night Movie of the Week Walker, Texas Ranger: Trial by Fire. The production was a continuation of the series, and not scripted to be a reunion movie. Norris reprised his role as Walker for the movie. He has stated that future Walker, Texas Ranger Movie of the Week projects are expected; however, this was severely impaired by CBS's 2006–2007 season decision to no longer regularly schedule Movies of the Week on Sunday night.

Chuck Norris facts originally started appearing on the Internet in early 2005. Created by Ian Spector, they are satirical factoids about Norris. Since then, they have become widespread in popular culture. The "facts" are normally absurd hyperbolic claims about Norris's toughness, attitude, virility, sophistication, and masculinity. Norris has written his own response to the parody on his website, stating that he does not feel offended by them and finds some of them funny,[98] claiming that his personal favorite is that they wanted to add his face to Mount Rushmore, but the granite is not hard enough for his beard.[99] At first it was mostly college students exchanging them, but they later became extremely widespread.[100]

From that point on, Norris started to tour with the Chuck Norris facts appearing on major talk shows, and even visiting troops in Iraq for morale boosting appearances.[101]

2006–present: Current works

Norris starred in the film The Cutter in 2006, where he plays a detective on a rescue mission.[102] That year time he published the novel The Justice Riders, co-written with Ken Abraham, Aaron Norris, and Tim Grayem.[103]

Gotham Books, the adult division of Penguin USA, released a book penned by Ian Spector entitled The Truth About Chuck Norris: 400 facts about the World's Greatest Human.[104] Norris subsequently filed suit in December against Penguin USA claiming "trademark infringement, unjust enrichment and privacy rights".[105] Norris dropped the lawsuit in 2008.[106] The book is a New York Times bestseller. Since then, Spector has published four more books based on Chuck Norris facts, these are Chuck Norris Cannot Be Stopped: 400 All-New Facts About the Man Who Knows Neither Fear Nor Mercy, Chuck Norris: Longer and Harder: The Complete Chronicle of the World's Deadliest, Sexiest, and Beardiest Man, The Last Stand of Chuck Norris: 400 All New Facts About the Most Terrifying Man in the Universe, and Chuck Norris Vs. Mr. T: 400 Facts About the Baddest Dudes in the History of Ever (also a New York Times bestseller).[107] That year Norris with the same team published a sequel to The Justice Riders called A Threat to Justice.[108] Tyndale House Publishers also published a book praising Norris, entitled The Official Chuck Norris Fact Book: 101 of Chuck's Favorite Facts and Stories, which was co-written and officially endorsed by him.[109]

In 2008, he published the political non-fiction book Black Belt Patriotism: How to Reawaken America, which reached number 14 on The New York Times best seller list in September 2008.[110] That same year, Gameloft produced the video game Chuck Norris: Bring On the Pain for mobile devices, based on the popularity Norris had developed on the internet with the Chuck Norris facts.[111] The player takes control of Norris in a side-scrolling beat 'em up. The game was well reviewed.[112]

Since 2010, Norris has been a nationally syndicated columnist with Creators Syndicate writing on both personal health issues and broader issues of health care in America.[113]

Throughout the 2010s, Norris appeared in advertisements for T-Mobile,[114] World of Warcraft,[115] BZ WBK,[116] the French TV show "Pieds dans le plat",[117] Hoegaarden,[118] United Healthcare,[119] Hesburger,[120][121][122][123] Cerveza Poker,[124] Toyota,[125] and in the 2020s, QuikTrip.[126]

In 2012, Norris played a mercenary in The Expendables 2.[127] The film was a success and grossed over $310 million worldwide.[128]

That same year, Norris and his wife Gena founded CForce Bottling Co. after an aquifer was discovered on his ranch.[129]

In 2017, Norris became Fiat's ambassador, a "tough face" for its commercial vehicles.[130] Flaregames produced Non Stop Chuck Norris, an isometric action-RPG game for mobile device and is the second game to be based on his popularity developed by the Chuck Norris facts. The game was well reviewed[131]

In 2019, Norris hosted the documentary Chuck Norris’ Epic Guide to Military Vehicles on the History Channel. In it Norris explores vehicular creations by the US military.[132]

In 2020, Norris acted in the series finale of Hawaii Five-0.[133][134]

In 2021, Norris was obtainable as a tank-commander in World of Tanks during the Holiday Ops event.[135] He gave players extra missions and featured a unique voice-over.

Martial arts knowledge

| Chuck Norris | |

|---|---|

| Style |

|

| Teacher(s) | |

| Rank |

|

Norris has founded two major martial arts systems: American Tang Soo Do and Chuck Norris System (formerly known as Chun Kuk Do).

American Tang Soo Do

American Tang Soo Do was formed in 1966 by Norris, which is combination of Moo Duk Kwan-style Tang Soo Do,[d] Judo and Karate (Shito-Ryu and Shotokan). Over the years it has been further developed by former black belts of his and their students.

Chuck Norris System

Norris's present martial art system is the Chuck Norris System, formerly known as Chun Kuk Do.[a][142][143][additional citation(s) needed]

The style was formally founded in 1990 as Chun Kuk Do by Norris, and was originally based on Norris's Tang Soo Do training in Korea while he was in the military.

During his competitive fighting career, Norris began to evolve the style to make it more effective and well-rounded by studying other systems such as Shōtōkan, Gōjū-ryū, Shitō-ryū, Enshin kaikan, Kyokushin, Judo, Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu, Arnis, Taekwondo, Tang Soo Do, Hapkido and American Kenpo. Chun Kuk Do now emphasizes self defense, competition, weapons, grappling, and fitness, among other things.[144] Each summer the United Fighting Arts Federation (UFAF) holds a training conference and the Chun Kuk Do world championship tournament in Las Vegas, Nevada.[145]

The art includes a code of honor and rules to live by. These rules are from Norris's personal code. They are:[146]

- I will develop myself to the maximum of my potential in all ways.

- I will forget the mistakes of the past and press on to greater achievements.

- I will continually work at developing love, happiness and loyalty in my family.

- I will look for the good in all people and make them feel worthwhile.

- If I have nothing good to say about a person, I will say nothing.

- I will always be as enthusiastic about the success of others as I am about my own.

- I will maintain an attitude of open-mindedness.

- I will maintain respect for those in authority and demonstrate this respect at all times.

- I will always remain loyal to my God, my country, family and my friends.

- I will remain highly goal-oriented throughout my life because that positive attitude helps my family, my country and myself.

Like most traditional martial arts, Chuck Norris System includes the practice of forms (Korean hyung and Japanese kata). The majority of the system's forms are adapted from Korean Tang Soo Do, and Taekwondo, Japanese Shitō-ryū, Shotokan Karate, Goju-ryu, Kyokushinkai Karate, Judo, Brazilian Jiu-jitsu, American Kenpo. It includes two organization-specific introductory forms, two organization-specific empty-hand forms, and one organization-specific weapon form (UFAF Nunchuk form, UFAF Bo form, UFAF Sai forms).[citation needed]

The United Fighting Arts Federation has graduated over 3,000 black belts in its history, and currently has nearly 4,000 active members world-wide.[147] There are about 90 member schools in the US, Mexico, Norway, and Paraguay.[citation needed]

Distinctions, awards, and honors

- While in the military, Norris's rank units were Airman First Class, 15th Air Force, 22d Bombardment Group, and 452d Troop Carrier Wing.

- Norris has received many black belts. These include a 10th degree black belt in Chun Kuk Do (founded 1990 by Chuck Norris. Based on his Tang Soo Do training in Korea while he was in military), a 9th degree black belt in Tang Soo Do[specify], an 8th degree black belt in Taekwondo, a 5th degree black belt in Karate[specify], a 3rd degree black belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu from the Machado family, and a black belt in Judo.[148]

- In 1967, he won the Sparring Grand Champions at the S. Henry Cho's All American Championship, and won it again the following year.[149]

- In 1968, he won the Professional Middleweight Karate champion title, which he held for six consecutive years.[5]

- In 1969, he won Karate's triple crown for the most tournament wins of the year.

- In 1969, he won the Fighter of the Year award by Black Belt magazine.

- In 1982, he won Action Star of the Year at the ShoWest Convention.

- In 1989, he received his Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

- In 1992, he won International Box Office Star of the Year at the ShoWest Convention.

- In 1997, he won the Special Award of being a Texas legend at the Lone Star Film & Television Awards.

- From 1997 to 1998, he won for three consecutive years the BMI TV Music Award at the BMI Awards.

- In 1999, Norris was inducted into the Martial Arts History Museum's Hall of Fame.

- In 1999, he was nominated for Favorite Actor in a Drama by the TV Guide Award.

- In 1999, he won the Inspirational Acting in Television Award at the Grace Prize Award.[150]

- On July 1, 2000, Norris was presented the Golden Lifetime Achievement Award by the World Karate Union Hall of Fame.

- In 2001, he received the Veteran of the Year at the American Veteran Awards.[97]

- In 2001, he won the Golden Boot at the Golden Boot Awards.

- On March 28, 2007, Commandant Gen. James T. Conway made Norris an honorary United States Marine during a dinner at the commandant's residence in Washington, D.C.[151]

- On December 2, 2010, he (along with brother Aaron) was given the title honorary Texas Ranger by Texas Governor Rick Perry.[152]

- In 2010, he won the Lifetime Achievement Award at the ActionFest.[153]

- In 2017, he was honored as an "Honorary Texan" because for many years he has lived at his Texas ranch near Navasota and he starred as Texas Ranger in his movie Lone Wolf McQuade and starred as ranger Cordell Walker in the TV series Walker, Texas Ranger.

- In 2020, two editions of a book honoring Norris were published titled Martial Arts Masters & Pioneers Biography: Chuck Norris – Giving Back For A Lifetime by Jessie Bowen of the American Martial Arts Alliance.[154]

- In 2024, a small statue was erected by Mihály Kolodkó at the eastern end of Megyeri Bridge in Budapest.[155][156]

Personal life

Family

Norris married his classmate Dianne Kay Holechek (born 1941) in December 1958 when he was 18 and Dianne was 17 years of age. They had met in 1956 at high school in Torrance, California. In 1962, their first child, Mike, was born. He also had a daughter in 1963 out of an extramarital affair.[157][158] Later, he had a second son, Eric, with his wife in 1964. After 30 years of marriage, Norris and Holechek were divorced in 1989, after separating in 1988 during the filming of The Delta Force 2.

On November 28, 1998, he married former model Gena O'Kelley, 23 years younger than Norris. O'Kelley had two children from a previous marriage. She delivered twins on August 30, 2001.[159]

On September 22, 2004, Norris told Entertainment Tonight's Mary Hart that he did not meet his illegitimate daughter from a past relationship until she was 26, although she learned that he was her father when she was 16. He met her after she sent a letter informing him of their relationship in 1990, one year after Norris's divorce from his first wife, Dianne Holechek.[160]

Norris has 13 grandchildren as of 2017[update].[161]

Christianity

An outspoken Christian,[162] Norris is the author of several Christian-themed books. On April 22, 2008, Norris expressed his support for the intelligent design movement when he reviewed Ben Stein's Expelled for Townhall.com.[163]

He is Baptist and a member of the Prestonwood Baptist Church (Southern Baptist Convention) in Dallas.[164]

Political views

Norris is a Republican and outspoken conservative.[165][166][167] Norris is a columnist for the far-right WorldNetDaily.[168][169][170]

In an interview following the release of the 1984 film Missing in Action, Norris stated that "I am a conservative, a real flag waver, a big Ronald Reagan fan. I'm not so much a Republican or Democrat; I go more for the man himself. Ronald Reagan says what he thinks, he's not afraid to speak his mind, even if he may be unpopular. I want a strong leader and he is a strong leader. And ever since he has been in office there has been a more positive, patriotic feeling in this country."[171]

Around the time of the filming of the 1986 film The Delta Force, Norris said—in response to the hijacking of TWA flight 847—that United States is becoming a "paper tiger" in the Middle East. "What we're facing here is the fact that our passive approach to terrorism is going to instigate much more terrorism throughout the world."[172] "I've been all over the world, and seeing the devastation that terrorism has done in Europe and the Middle East, I know eventually it's going to come here," added Norris. "It's just a matter of time. They're doing all this devastation in Europe now, and the next stepping stone is America and Canada. Being a free country, with the freedom of movement that we have, it's an open door policy for terrorism. It's like Khadafy [sic] said a few weeks ago. 'If Reagan doesn't back off, I'm going to release my killer squads in America.' And there's no doubt in my mind that he has them."[173]

In 2007, Norris took a trip to Iraq to visit U.S. troops.[174][175]

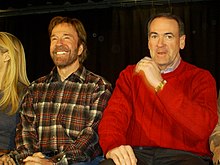

Norris supported Mike Huckabee's failed candidacy in the 2008 Republican Party presidential primaries, where he made headlines for calling the eventual Republican nominee, John McCain, too old to handle the pressures of being president.[176][177] He voiced his support for McCain in the 2008 presidential election, emphasizing his enthusiasm for McCain's partner on the Republican ticket, Sarah Palin.[178]

On November 18, 2008, Norris became one of the first members of show business to express support for the California Proposition 8 ban on same-sex marriage, and he criticized activists for not accepting the democratic process and the apparent double standard he perceived in criticizing the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints without criticizing African Americans, most of whom who had voted for the measure.[179]

In 2009, Norris had expressed support for the Barack Obama "birther" conspiracy. In his letter, released at WorldNetDaily, Norris deemed then-President Obama's refusal to disclose his birth certificate suspicious and implored him to put an end to the conspiracy theories.[180][181]

On April 11, 2011 Norris had written a five-part investigation regarding the "infiltration of Sharia law into United States culture" for WorldNetDaily.[182][183]

On June 26, 2012, Norris published an article on Ammoland.com, in which he accused the Obama administration of paying Jim Turley, one of the national board members of the Boy Scouts of America at the time, to reverse the organization's policy that excluded gay youths from joining.[184]

During the 2012 presidential election, Norris first recommended Ron Paul, and then later formally endorsed Newt Gingrich as the Republican presidential candidate.[185] After Gingrich suspended his campaign in May 2012, Norris endorsed Republican presumptive nominee Mitt Romney, despite Norris having previously accused Romney of flip-flopping and of trying to buy the nomination for the Republican Party candidacy for 2012.[186] On the eve of the election, he and his wife Gena made a video warning that if evangelicals did not show up at the polls and vote out President Obama, "...our country as we know it may be lost forever...".[187][188]

Norris has visited Israel, and he voiced support for former Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in the 2013 and 2015 elections.[189][190] Norris endorsed Huckabee again in the 2016 Republican primaries before he dropped out.[191] In March 2016, it was reported that Norris endorsed Republican Texas Senator Ted Cruz and that he would be attending a Cruz rally,[192][193] but two days later, Norris stated he would only endorse the GOP nominee once that nominee has been nominated by the party.[194] In July 2016, Norris encouraged Republican voters to unify and elect G.O.P. nominee Donald Trump. [195] Later, Norris endorsed former Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore in the 2017 United States Senate special election in Alabama.[196]

In 2019, Norris signed an endorsement deal with gun manufacturer Glock. The deal was met with criticism from some members of the public and some of his fans, who felt it was in bad timing due to the increase in school shootings in the United States.[197]

In 2021, Norris announced his support of the 2021 gubernatorial election to recall incumbent Governor Gavin Newsom and endorsed radio talk show host Larry Elder to replace him.[198]

Philanthropy

In 1990, Norris established the United Fighting Arts Federation and Kickstart Kids. As a significant part of his philanthropic contributions, the organization was formed to develop self-esteem and focus in at-risk children as a tactic to keep them away from drug-related pressure by training them in martial arts. Norris hopes that by shifting middle school and high school children's focus towards this positive and strengthening endeavor, these children will have the opportunity to build a better future for themselves.[97][199] Norris has a ranch in Navasota, Texas, where they[who?] bottle water;[200] a portion of the sales support environmental funds and Kickstart Kids.

He is known for his contributions towards organizations such as Funds for Kids, Veteran's Administration National Salute to Hospitalized Veterans, the United Way, and the Make-A-Wish Foundation in the form of donations as well as fund-raising activities.[97]

His time with the U.S. Veterans Administration as a spokesperson was inspired by his experience serving the United States Air Force in Korea. His objective has been to popularize the issues that concern hospitalized war veterans such as pensions and health care. Due to his significant contributions, and continued support, he received the Veteran of the Year award in 2001 at the American Veteran Awards.[97]

In India, Norris supports the Vijay Amritraj Foundation, which aims to help victims of disease, tragedy and circumstance. Through his donations, he has helped the foundation support Paediatric HIV/AIDS homes in Delhi, a blind school in Karnataka, and a mission that cares for HIV/AIDS-infected adults, as well as mentally ill patients in Cochin.[201]

Filmography

Bibliography

- Winning Tournament Karate (1975)

- Toughen Up! The Chuck Norris Fitness System (1983)

- The Secret of Inner Strength: My Story (1987)

- The Secret Power Within: Zen Solutions to Real Problems (1996)

- Against All Odds: My Story (2004)

- The Justice Riders (2006)

- A Threat to Justice (2007)

- Black Belt Patriotism: How to Reawaken America (2008). Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59698-558-2.

- The Official Chuck Norris Fact Book: 101 of Chuck's Favorite Facts and Stories (2009)

Notes

References

- ^ a b "Chuck Norris Earns 3rd Degree Black Belt in BJJ". Fightland.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ Norris, Chuck; Hyams, Joe (1988). "1". The Secret of Inner Strength: My Story (1st ed.). Boston: Little, Brown and Co. p. 6. ISBN 0-316-61191-3.

- ^ a b c Norris, Chuck; Ken Abraham (2004). Against All Odds: My Story. Broadman & Holman Publishers. ISBN 0-8054-3161-6.

- ^ a b Berkow, Ira (May 12, 1993). "At Dinner with: Chuck Norris". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Chuck Norris – Strong, Silent, Popular". The New York Times. September 1, 1985.

- ^ "Chuck Norris Fights to Be a Better Actor in 'Hero and the Terror' Role". Los Angeles Times. September 2, 1988. Archived from the original on August 23, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ "Breaking the Silence: People.com". www.people.com. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ Wedlan, Candace A. (October 2, 1996). "Body Watch; Kicking Old Habits; Chuck Norris found he couldn't eat just anything after he hit his mid-30s. These days, TV's top ranger feasts on veggies, fowl and fish. And he tries to keep his distance from peanut clusters". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Theisen, Blake Stilwell, Tiffini (May 19, 2023). "Famous Veterans: Chuck Norris". Military.com. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "#VeteranOfTheDay Air Force Veteran Chuck Norris – VA News". March 10, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ^ Boatner, Verne (May 2, 1975). "If I can do it, you can do it". Arizona Republic. p. D-1.

- ^ "Torrance karate expert wins Crown". Los Angeles Times. Vol. LXXXVI. June 5, 1967.

- ^ "Karate bouts at Garden". Daily News. Vol. 48. June 23, 1967.

- ^ "Redondo's Norris wins karate title". Los Angeles Times. Vol. LXXVI. June 25, 1967.

- ^ "Sport Briefs". Spokane Chronicle. June 26, 1967. p. 14.

- ^ "Chuck Norris Blog". Archived from the original on February 8, 2010.

- ^ "Californian wins Karate championship". Dayton Daily News. April 1, 1968. p. 19.

- ^ "Past Sparring Grand Champions". Henrycho.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ "Lewis crowned king of karate". Independent. August 4, 1969.

- ^ "Karate champions to gather at Long Beach". Valley Times. Vol. 32. July 30, 1969.

- ^ "Chuck Norris takes karate black belt". Valley News. Vol. 58. August 9, 1969.

- ^ Krizanovich, Karen (2015). Infographic Guide To The Movies. Hachette UK. pp. 18–9. ISBN 978-1-84403-762-9. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2019.

- ^ "Yellow Faced Tiger – aka Slaughter in San Francisco (1974) Review". Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Slaughter in San-Francisco (VHS). Embassy Home Entertainment. 1985. VHS 7645.

- ^ "Oceanside-Carlsbad Movie Guide". Times-Advocate. May 15, 1981.

- ^ Cedrone, Lou (September 2, 1981). "It's been a very good summer for movie industry and fans and many are still around". The Evening Sun. Vol. 143.

- ^ Gross, Linda (October 28, 1981). "'The Unseen' Is Best Left Unseen". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Ask showcase". The Tennessean. Vol. 76. June 14, 1981.

- ^ Norris, Chuck (May 1, 1975). Winning Tournament Karate. Black Belt Communications. ASIN 0897500164 .

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Imperial College TV (July 10, 2011). "Chuck Norris Interview 1980". Archived from the original on March 12, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Chuck Norris Movies: Lone Wolf McQuade and 23 Other Action Films Remembered By the Martial Arts Icon – – Black Belt". blackbeltmag.com. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "Good Guys Wear Black (1978) – Financial Information". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Cook, David A. (2002). Lost Illusions: American Cinema in the Shadow of Watergate and Vietnam, 1970–1979. University of California Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-520-23265-5. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "Blu-ray Review – A Force of One (1979)". August 3, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "A Force of One (1979) – Financial Information". Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "The Octagon (1980) review". www.coolasscinema.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "The Octagon (1980)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Chuck Norris: action vs. violence, March 19, 1982, archived from the original on December 2, 2020, retrieved June 19, 2018

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "Lone Wolf McQuade". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- ^ "Lone Wolf McQuade". Variety. December 31, 1982. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (April 16, 1983). "Villainy dispatched in el paso". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ Norris, Chuck (May 1, 1983). Toughen Up! the Chuck Norris Fitness System. Bantam Dell Pub Group. ASIN 055301465X .

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Warner Movies On Demand (October 1, 2015), Electric Boogaloo: The Wild, Untold Story of Cannon Films, archived from the original on April 30, 2019, retrieved March 29, 2018

- ^ "PFC Wieland Clyde Norris". The Virtual Wall.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Missing in Action II: The Beginning (1985)". Box Office Mojo. December 14, 1985. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ Andrew Yule, Hollywood a Go-Go: The True Story of the Cannon Film Empire, Sphere Books, 1987 p111

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Chuck Norris Breaks The Stereotype In 'Code Of Silence'". Chicago Tribune. May 3, 1985. Archived from the original on August 7, 2011. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ "Code of Silence". Variety. December 31, 1984. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ "Code of Silence". Chicago Sun Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (May 3, 1985). "Screen: Chuck Norris Is a Chicago Police Inspector in 'Code of Silence'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 21, 2013. Retrieved December 15, 2010.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Good Guys Wear Black (1978) – Financial Information". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Sussman, Soll (September 13, 1986). "Swashbuckler hero turns to comedy". The Canberra Times. Vol. 61, no. 18, 609. p. B7.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 21, 1986). "Firewalker". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (November 21, 1986). "Firewalker Movie Review". The New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ "Firewalker: Review". TV Guide. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Bentley, Rick (December 2, 1986). "'Firewalker' movie has right blend to spoof adventure films". The Town Talk. pp. C-7.

- ^ "Film Reviews: Firewalker". Variety. November 26, 1986. 14.

- ^ "Firewalker Movie Review". The Washington Post. November 21, 1986. Retrieved November 7, 2010.

- ^ Severson, Ed (November 26, 1986). "'Firewalker' is an entertaining turkey". Arizona Star. pp. Seven B.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (November 24, 1986). "'Firewalker' Is Handsome Hokum". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Firewalker (1986) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ Norris, Chuck; Hyams, Joe (February 1, 1989). The Secret of Inner Strength: My Story. Diamond Books. ISBN 1557731756.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ Lipper, Hal (August 28, 1988). "Chuck Norris He wants emotion to add punch to his characters". Tampa Bay Times. Vol. 105. p. 83 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "A New Kick For Norris Macho Martial Arts Man Chuck Norris Welcomes The Chance To Soften His Public Image In His Latest Movie". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ Howle, Paul (September 26, 1990). "In their own word: Chuck Norris". The News-Press. p. Close up Cape Coral: 9.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Forest Warrior". TV Guide. Retrieved July 25, 2021.

- ^ King, Susan (April 18, 1993). "Chuck Norris: Karate Champ Turned Action-film Actor Turned Series Star?". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2011. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- ^ "Premiere of 'Trouble with Larry' on Ch. 11 at 7 p.m.". The Galveston Daily News. August 25, 1993. p. 6-B.

- ^ "Casket Match: Undertaker def. Yokozuna". WWE. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- ^ WWE: Jeff Jarrett Gets Roundhouse Kick By Chuck Norris!!!. YouTube. GCXtremeBoomboxUnit. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021.

- ^ Norris, Chuck (January 3, 1996). The Secret Power Within: Zen Solutions to Real Problems. Little, Brown & Company. ISBN 9780316583503. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Total Gym – History". www.totalgym.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (November 1, 1998). "Chuck Norris Day". Standard-Speaker.

- ^ Bauder, David (November 5, 1998). "Temptations movie makes sweet music for NBC". The Morning Call.

- ^ Hal Erickson (2015). "The President's Man 2: A Line In the Sand (2002)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 17, 2015. Retrieved October 3, 2015.

- ^ "The Bells of Innocence". TV Guide. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "Yes, Dear". TV Guide. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ Sources:

- "Dodgeball". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- "Dodgeball – A True Underdog Story". Rotten Tomatoes. June 18, 2004. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- "Dodgeball: A True Underdog Story". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

- "CinemaScore". cinemascore.com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Jessica Lahm (2023) Chuck Norris[1] Faces of Philanthropy

- ^ "Web Archive: Chuck Norris". Archived from the original on October 19, 2006. Retrieved November 3, 2006.

- ^ "Chuck Norris facts read by Chuck Norris". YouTube. March 11, 2006. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ^ MrNorrisVideos (October 2, 2011). "Chuck Norris Fever – 2006". Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Sources:

- chucknorrisfacts (March 3, 2006). "Chuck Norris on The Tony Danza Show". Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via YouTube.

- Pepos Con (May 24, 2008). "Chuck Norris, Jokes of Himself and by Himself". Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via YouTube.

- CNBCOnTheMoney (March 24, 2009). "Chuck Norris faces the Facts (April 12 on CNBC)". Archived from the original on September 30, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via YouTube.

- Tyndale House Publishers (November 17, 2009), The Chuck Norris Fact Book: Chuck Norris visits Iraq, archived from the original on May 31, 2019, retrieved March 29, 2018

- MrNorrisVideos (October 2, 2011), Chuck Norris Fever – 2006, archived from the original on May 31, 2019, retrieved March 29, 2018

- ^ "The Cutter". BBFC.

- ^ Norris, Chuck; Abraham, Ken; Norris, Aaron (September 1, 2006). The Justice Riders: A Novel. B&H Fiction. ISBN 0805444300.

- ^ Ian Spector (2007). The Truth About Chuck Norris: 400 Facts About the World's Greatest Human. Gotham. ISBN 978-1-59240-344-8.

- ^ Kearney, Christine (December 21, 2007). "Chuck Norris sues, says his tears no cancer cure". Reuters. Archived from the original on December 24, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Chuck Norris kicks suit vs. L.I. student". NY Daily News. May 28, 2008. Archived from the original on August 26, 2018. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- ^ "Ian Spector – Penguin Random House". www.penguinrandomhouse.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "A Threat to Justice". www.goodreads.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ The Official Chuck Norris Fact Book Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Tyndale House Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4143-3449-3

- ^ "The New York Times Best Seller List" (PDF). Hawes Publications. September 28, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ "Gameloft Releases Chuck Norris: Bring on the Pain". July 17, 2008. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Sources:

- "Chuck Norris: Bring on the Pain! Review". Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Chuck Norris: Bring on the Pain review". Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Chuck Norris: Bring on the Pain for IPhone". PCWorld. December 4, 2009. Archived from the original on December 1, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Chuck Norris: Bring on the Pain cell-phone game by GameLoft". www.videogamesblogger.com. August 27, 2008. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Chuck Norris: Bring on the Pain! My Games Statistics for iOS (iPhone/iPad) – Collections, Tracking and Ratings – GameFAQs". www.gamefaqs.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "About Chuck Norris". Creators Syndicate. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Chuck Norris shills for T-Mobile ads". The Prague Post. November 10, 2010. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ^ "World of Warcraft TV Commercial: Chuck Norris – Hunter". YouTube. December 15, 2011. Archived from the original on December 15, 2011. Retrieved December 15, 2011.

- ^ "Polish bank BZ WBK commercials with Chuck Norris". January 20, 2012. Archived from the original on September 22, 2013. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "Cyril Hanouna et Chuck Norris : danse de l'épaule délirante pour la promo d'Europe 1". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ Inc, Untitled (November 16, 2016). "Hoegaarden – Chuck Norris". Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via Vimeo.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Chuck Norris Jokes Have Real Medical Consequences in Latest UnitedHealthcare Spot". Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "Hesburger – Chuck Norris tähdittää Hesburgerin mainoksia". www.hesburger.fi. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "Hesburger – Haastattelussa Chuck Norris". www.hesburger.fi. Archived from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "Chuck Norris on Instagram: "Here's a recent commercial I did for my friends at Hesburger. Thanks for watching, Chuck Norris…"". Instagram. Archived from the original on December 23, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ Kun Chuck Norris menee Hesburgeriin – hän ei jonota. Hesburger (Commercial) (in Finnish). February 21, 2018. Event occurs at 0:01. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved February 25, 2020.

- ^ CervezaPokerColombia (March 15, 2018), Cerveza Poker – Chuck Norris sale en una tapa. Amistad Letal 2 Una fiesta de altura., archived from the original on May 31, 2019, retrieved March 27, 2018

- ^ "Watch a Toyota gain Chuck Norris's powers in this funny advert". Motor1.com. Archived from the original on August 19, 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2018.

- ^ "Chuck Norris stars in QuikTrip commercials". KOKI. January 9, 2020. Archived from the original on January 29, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "The Expendables 2 (2012) – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 15, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ "About Us – CForce". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "Chuck Norris now the face of Fiat Professional vehicles". Motor Authority. June 1, 2017. Archived from the original on June 1, 2017. Retrieved June 2, 2017.

- ^ Sources:

- flaregames (December 13, 2017). "Nonstop Chuck Norris". Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via Google Play.

- "Nonstop Chuck Norris review – Entertainment Focus". www.entertainment-focus.com. April 20, 2017. Archived from the original on November 22, 2018. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Nonstop Chuck Norris Review: Deja Chuck". April 25, 2017. Archived from the original on December 26, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- "Nonstop Chuck Norris on the App Store". App Store. Archived from the original on November 20, 2017. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ "Chuck Norris Has a New Show About Badass Military Vehicles". Popular Mechanics. July 8, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2023.

- ^ Mitovich, Matt Webb (March 5, 2020). "Hawaii Five-0 Series Finale First Look: Chuck Norris Books a Badass Role". Archived from the original on March 24, 2020. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Hawaii Five-0 Fans React To Legend Chuck Norris' Cameo". Cinemablend. April 3, 2020. Archived from the original on April 9, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ "Holiday Ops 2021: Event Guide | General News | World of Tanks". worldoftanks.eu. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ "Tang Soo Do World". www.tangsoodoworld.com. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ Lindsey, Alex (August 12, 2019). "BJJ History: Chuck Norris Builds the First JJ Machado Academy in the USA". Grappling Insider. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Master Carlos Machado Lineage & History". Carlos Machado Jiu Jitsu Mid Cities. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Your Home For Professional Brazilian Jiu Jitsu Training". Central Texas Brazilian Jiu Jitsu. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2020.

- ^ "Rigan Machado | BJJ Heroes". Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ "IBK International Kyokushin Budokai – Black Belts". International Kyokushin Budokai. Archived from the original on November 9, 2019. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ "Welcome to the United Fighting Arts Federation (UFAF) and the Chuck Norris System!". www.ufaf.org. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to the United Fighting Arts Federation (UFAF) and Chun Kuk Do!". www.ufaf.org. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ "About the Chuck Norris System". United Fighting Arts Federation. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved March 11, 2018.

- ^ Jeffrey, Douglas. "Wright Finally KOed—By Chuck Norris—at UFAF Convention". Black Belt Magazine. December 1993. p. 20.

- ^ "Welcome to the United Fighting Arts Federation (UFAF) and Chun Kuk Do!". United Fighting Arts Federation. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- ^ Rimington, Dana. "72-year-old can Chun Kuk Do / Layton senior's focus turns from fancy writing to fancy footwork". Standard-Examiner. Saturday, August 28, 2010

- ^ BJJ Instructors and Students. "BJJ Genius". Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ^ "Past Sparring Grand Champions". www.henrycho.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- ^ MrNorrisVideos (September 20, 2011). "1999 TV Award "Grace Prize" – Chuck Norris for "Walker, Texas Ranger" – 2000". Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Conway makes Chuck Norris honorary Marine – Marine Corps News | News from Afghanistan & Iraq". Marine Corps Times. Archived from the original on December 27, 2012. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- ^ Norris, Chuck (December 2, 2010). "Former TV lawman Chuck Norris to be given honorary Texas Ranger title by Gov. Rick Perry today in Garland". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved December 12, 2010.

- ^ MrNorrisVideos (August 26, 2011). "Chuck Norris – ActionFest – Lifetime Achievement Award – 2010 (Part 1/2)". Archived from the original on May 31, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2018 – via YouTube.

- ^ Bowen, Jessie (June 9, 2020). Martial Arts Masters & Pioneers Biography: Chuck Norris – Giving Back For A Lifetime (1st ed.). US: Independently published. p. 424. ISBN 979-8650086956.

- ^ "Miért fekszik megkötözve Chuck Norris a Megyeri hídon?".

- ^ Budapest, We love (April 2, 2024). "New Kolodko sculpture appeared depicting Chuck Norris - English - We love Budapest". welovebudapest.com. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ "Chuck Norris Didn't Need a DNA Test to Accept Daughter He Didn't Know He Had | "It Was as If I Had Known Her All My Life"". her.womenworking.com. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ "Herald Extra: Chuck Norris". Archived from the original on March 25, 2008.

- ^ "Gena Norris Notes". Tv.com. May 3, 2006. Archived from the original on April 14, 2009.

- ^ Hart, Mary (September 22, 2004). "At Home and Up-Close with Chuck Norris". etonline.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2006.

- ^ "mentorsharbor.com". Mentorsharbor.com. Archived from the original on October 3, 2012.

- ^ See External Links Drew Marshall Interview

- ^ Norris, Chuck (April 22, 2008). "Win Ben Stein's Monkey". Townhall. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved April 22, 2008.

- ^ Sara Horn, Chuck Norris tells how God's plan was bigger than his own, baptistpress.com, USA, September 21, 2004

- ^ Thomsen, Jacqueline (August 7, 2017). "Chuck Norris endorses ex-judge Moore in Alabama GOP Senate primary". The Hill. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- ^ "And the latest Chuck Norris political endorsement goes to". Washington Post. August 8, 2017. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "5 reasons Chuck Norris wants you to vote for Donald Trump". NJ.com/Advance Publications. January 16, 2019. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ "WorldNet Daily Continues to Pump Out Outrageous Propaganda". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ Roth, Zachary (May 15, 2015). "Chuck Norris: I never said Jade Helm aimed to take over Texas!". MSNBC. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "'Texas Ranger' Chuck Norris warns of government plot to take over state". The Guardian. May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ 'I really appreciate the acclaim' Norris basks in limelight KLEMESRUD, JUDY. The Globe and Mail3 Sep 1985: S.7.

- ^ CAROL LAWRENCE JOINS A `NEW CAST': [SUN-SENTINEL Edition] Sun Sentinel 5 July 1985: 2.A.

- ^ Action star Chuck Norris an intelligent Rambo: [FIN Edition] Ron Base Toronto Star. Toronto Star 11 Feb 1986: F4.

- ^ "Norris documentary shines light on troops overseas". WaxahachieTX.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013.

- ^ "Martial arts program for kids to start". The Ellis County Press. May 21, 2009. Archived from the original on August 16, 2013.

- ^ Savage, Charlie (January 17, 2008). "Huckabee campaign is more than a cameo for Chuck Norris". The New York Times. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ "Norris says McCain is too old to be president". NBC News. The Associated Press. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ McSherry, Alison (September 15, 2008). "Listen Up, America: Chuck Norris' Vision". Roll Call. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ Norris, Chuck (November 18, 2008). "If Democracy Doesn't Work, Try Anarchy". Townhall. Archived from the original on May 10, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ Weiner, Rachel (May 25, 2011). "Chuck Norris On Birthers: "I Agree With CNN's Lou Dobbs"". HuffPost. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

I agree with CNN's Lou Dobbs, who was chastised by his own media outlet for demanding the release of your original birth certificate. Why was that such a bad request? [...] Mr. President, as more and more people realize that you are refusing to release your original birth certificate, further questions will fuel the fires of debate or at least hinder the embers from ever being snuffed out. Questions such as, "Does it really contain the Hawaiian physician's name?" "Does it disclose something other than his birthplace that he wishes others not to see?"

- ^ Schulman, Daniel (August 3, 2009). "Chuck Norris Challenges Obama on Birth Certificate". Mother Jones. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Weiner, Juli (April 18, 2011). "Chuck Norris: Sharia Law Invading U.S. Like a "Frog Boiled in a Kettle by a Slow Simmer"". Vanity Fair. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ Murphy, Tim (April 18, 2011). "Koran Scholar Chuck Norris Warns Of Creeping Sharia". Mother Jones. Retrieved February 16, 2023.

- ^ "Is Obama Creating a Pro-Gay Boy Scouts of America?". Archived from the original on January 6, 2013. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Reilly, Mollie (January 20, 2012). "Chuck Norris Endorses Newt Gingrich For President". The HuffingtonPost. Archived from the original on August 17, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

- ^ Poppleton, Travis. "Chuck Norris slams Romney, endorses Newt Gingrich for president". KSL. Archived from the original on October 25, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- ^ Bingham, Amy (September 4, 2012). "Chuck Norris Warns of '1,000 years of Darkness' If Obama Re-Elected". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ Gunter, Booth (November 4, 2012). "Six most paranoid fears for Obama's second term". Salon.com. Archived from the original on November 12, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2012.

- ^ "What is Chuck Norris doing in Israel?". The Jerusalem Post. February 5, 2017. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Becker, Gahl; Froim, Yoni (February 6, 2017). "Chuck Norris arrives in Israel, peace seems imminent". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ "Celebrity endorsements for 2016". The Hill. April 25, 2015. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ "Chuck Norris Endorses Ted Cruz". March 8, 2016. Archived from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Heil, Emily (March 8, 2016). "Roundhouse kick! Chuck Norris to stump for Ted Cruz". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Recio, Maria (March 10, 2016). "Chuck Norris Bows Out of Cruz Event". The Star-Telegram. Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- ^ Norris, Chuck (July 24, 2016). "The people have spoken * WorldNetDaily * by Chuck Norris". WorldNetDaily. Retrieved August 18, 2024.

- ^ Thomsen, Jacqueline (August 7, 2017). "Chuck Norris Endorses Ex-Judge Moore in Alabama GOP Senate Primary". The Hill. Archived from the original on August 10, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ "Chuck Norris slammed for becoming face of Glock". Yahoo.com. April 19, 2019. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- ^ Greg Albough (July 22, 2021). "Conservative Powerhouse Restored To California Governor's Recall Race". Citizens Journal.

- ^ "A Renaissance Man". Inside Kung Fu. Archived from the original on December 19, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- ^ Surette, Rusty (January 11, 2017). "Chuck Norris and wife open new bottled water production facility in Navasota". kbtx.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Chuck Norris's Charity Work, Events and Causes". Looktothestars.org. Archived from the original on November 27, 2011. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

Further reading

- The Secret Power Within: Zen Solutions to Real Problems, Zen Buddhism and martial arts. Little, Brown and Company (1996). ISBN 0-316-58350-2.

- Against All Odds: My Story, an autobiography. Broadman & Holman Publishers (2004). ISBN 0-8054-3161-6.

- The Justice Riders, Wild West novels. Broadman & Holman Publishers (2006). ISBN 0-8054-4032-1.

- Spector, Ian (2007). The Truth About Chuck Norris. New York:Gotham Books. ISBN 1-59240-344-1.

External links

- Official website

- Chuck Norris at the British Film Institute[better source needed]

- Chuck Norris at IMDb

- Chuck Norris. Archived October 20, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at martialinfo.com. Archived August 26, 2019, at the Wayback Machine.

- Official Chun Kuk Do Website

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Chuck Norris

- 1940 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American non-fiction writers

- 20th-century Baptists

- 21st-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American non-fiction writers

- 21st-century Baptists

- Activists from California

- Activists from Oklahoma

- Activists from Texas

- Actors from Torrance, California

- American Christian creationists

- American chun kuk do practitioners

- American evangelicals

- American gun rights activists

- American male film actors

- American male karateka

- American male non-fiction writers

- American male screenwriters

- American male taekwondo practitioners

- American male television actors

- Martial arts writers

- American motivational writers

- American people of Irish descent

- American people who self-identify as being of Cherokee descent

- American philanthropists

- American political commentators

- American political writers

- American practitioners of Brazilian jiu-jitsu

- American tang soo do practitioners

- Baptists from California

- Baptists from Oklahoma

- Baptists from Texas

- Baptist writers

- California Republicans

- Film producers from California

- Film producers from Oklahoma

- Film producers from Texas

- Intelligent design advocates

- Male actors from California

- Male actors from Oklahoma

- Male actors from Texas

- Martial arts school founders

- People awarded a black belt in Brazilian jiu-jitsu

- People from Jefferson County, Oklahoma

- People from Navasota, Texas

- People from Prairie Village, Kansas

- People from Ryan, Oklahoma

- People from Tarzana, Los Angeles

- Protestants from California

- Screenwriters from California

- Screenwriters from Oklahoma

- Screenwriters from Texas

- Southern Baptists

- Texas Republicans

- United States Air Force airmen

- WorldNetDaily people

- Writers from Los Angeles

- Writers from Oklahoma

- Writers from Texas