Mexia, Texas

Mexia | |

|---|---|

| Mexia, Texas | |

| Motto(s): A great place to live, no matter how you pronounce it | |

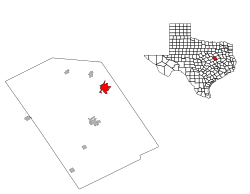

Location of Mexia, Texas | |

| |

| Coordinates: 31°39′44″N 96°29′50″W / 31.66222°N 96.49722°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| County | Limestone |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7.30 sq mi (18.90 km2) |

| • Land | 7.20 sq mi (18.64 km2) |

| • Water | 0.10 sq mi (0.25 km2) |

| Elevation | 532 ft (162 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 6,893 |

| • Density | 1,020.28/sq mi (393.95/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 76667 |

| Area code | 254 |

| FIPS code | 48-47916[3] |

| GNIS feature ID | 2411092[2] |

| Website | cityofmexia |

Mexia (/məˈheɪə/ mə-HAY-ə)[4] is a city in Limestone County, Texas, United States. The population was 6,893 at the 2020 census.

The city's motto, based on the fact that outsiders tend to mispronounce the name as /ˈmɛksiə/ (MEK-see-ə), is "A great place to live, no matter how you pronounce it."[5]

Named after General José Antonio Mexía, a Mexican hero for the Republic of Texas Army during the Texas Revolution, the town was founded near his estate. Nearby attractions include Fort Parker Historical recreation, the Confederate Reunion grounds, and Mexia State Supported Living Center (formerly Mexia State School), which began as a prisoner of war camp for members of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps during World War II.

Mexia is also home to the Mexia Public Schools Museum, one of a few museums dedicated to the historical and social significance of a Texas public school system.

Late model Anna Nicole Smith attended Mexia Public Schools.

Mexia hosts a large Juneteenth celebration every year.

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 5.2 square miles (13 km2), all land.

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1890 | 1,674 | — | |

| 1900 | 2,393 | 43.0% | |

| 1910 | 2,694 | 12.6% | |

| 1920 | 3,482 | 29.3% | |

| 1930 | 6,579 | 88.9% | |

| 1940 | 6,410 | −2.6% | |

| 1950 | 6,627 | 3.4% | |

| 1960 | 6,121 | −7.6% | |

| 1970 | 5,943 | −2.9% | |

| 1980 | 7,094 | 19.4% | |

| 1990 | 6,933 | −2.3% | |

| 2000 | 6,563 | −5.3% | |

| 2010 | 7,459 | 13.7% | |

| 2020 | 6,893 | −7.6% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[6] | |||

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (NH) | 2,213 | 32.11% |

| Black or African American (NH) | 2,086 | 30.26% |

| Native American or Alaska Native (NH) | 19 | 0.28% |

| Asian (NH) | 33 | 0.48% |

| Pacific Islander (NH) | 8 | 0.12% |

| Some Other Race (NH) | 10 | 0.15% |

| Mixed/Multi-Racial (NH) | 178 | 2.58% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 2,346 | 34.03% |

| Total | 6,893 |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 6,893 people, 2,487 households, and 1,586 families residing in the city.

As of the census[3] of 2008, there were 6,552 people, 2,427 households, and 1,660 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,273.9 inhabitants per square mile (491.9/km2). There were 2,750 housing units at an average density of 533.8 per square mile (206.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 55.90% White, 31.68% African American, 0.23% Native American, 0.20% Asian, 10.67% from other races, and 1.33% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 17.90% of the population.

There were 2,427 households, out of which 36.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.7% were married couples living together, 19.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.6% were non-families. 28.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.63 and the average family size was 3.21.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 30.1% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 25.0% from 25 to 44, 18.5% from 45 to 64, and 16.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 84.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $22,785, and the median income for a family was $29,375. Males had a median income of $26,479 versus $18,138 for females. The per capita income for the city was $12,235. About 20.8% of families and 22.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 28.5% of those under age 18 and 15.2% of those age 65 or over.

History

[edit]

Mexia was founded as a town in the 19th century. Inhabitants occupied the Fort Parker settlement near the Navasota river. The area is near where the rolling hills of the great plains begin. The hills provided grazing land for the buffalo herds, which plains Indians depended upon for sustenance. Many hunting artifacts from Native American people have been found in the creek beds and draws around Mexia. The Comanche tribe came into conflict with the white settlers in this area. The abduction of Cynthia Ann Parker took place at Fort Parker. Comanches raided the fort and took the nine-year-old Parker girl. She lived among the Comanche people into adulthood and was the mother of Quanah Parker, the last Comanche war chief.

Mexia is at the intersection of US Highway 84 and State highways 14 and 171, twelve miles northeast of Groesbeck in northeastern Limestone County. It was named for the Mexía family, who in 1833 received an eleven-league land grant that included what is now the townsite. The town was laid out in 1870 by a trustee of the Houston and Texas Central Townsite Company, which offered lots for sale in 1871, as the Houston and Texas Central Railway was completed between Hearne and Groesbeck. The Mexia post office began operation in 1872, and the community was incorporated with a mayoral form of government in 1873 by an act of the legislature. J.C. Yarbro was the first mayor.[10] The city's first newspaper, the Ledger, was established in Fairfield in 1869 and moved to Mexia in 1872. By 1880 Mexia also had four schools, three churches, and a variety of businesses to serve its 1,800 residents; by 1885 the town had a gas works, an opera house, two banks, two sawmills, and 2,000 residents. The Mexia Democrat was established in 1887 and the Weekly News in 1898. Between 1904 and 1906 the Trinity and Brazos Valley Railway built track between Hillsboro and Houston, making Mexia a commercial crossroads for area farmers.

In 1912 the Mexia Gas and Oil Company drilled ten dry holes, but in the eleventh attempt discovered a large natural gas deposit.[11] The Mexia oilfield was discovered in 1920, by Colonel Albert E. Humphreys and his geologist F. Julius Fohs. Oil production peaked in November 1921 at 53,000 BOPD.[12] The population of Mexia increased from 3,482 to nearly 35,000. The rapid growth was excessive for local authorities, and for a short time in 1922 Mexia was under martial law. That year, production for the Mexia field was 35 million barrels produced. Cumulative production of the field totaled 108 million barrels by the mid-1980s. In 1924 Mexia residents passed a new city charter that changed the local government to a city manager system. After the initial oil boom, the population of Mexia declined to 10,000 by the mid-1920s. The prosperity generated by the boom continued until the 1930s, when the Great Depression forced many people to leave in search of work. The number of residents stabilized at 6,500 in the early 1930s, but the number of businesses fell from 280 to 190. In 1942 a camp for prisoners of war was established at Mexia; the facility was converted in 1947 for use as the Mexia State School, which became one of the community's principal employers. The population was reported as 6,618 in the early 1950s, 5,943 in the early 1970s, 7,172 in the late 1980s, and 6,933 in 1990. In 2000 the population was listed as 6,563.[13]

Mexia made national news in 1981, when three young black men drowned in Lake Mexia after being taken into custody by law enforcement officers for possession of marijuana during the annual Juneteenth celebration.[14] Carl Baker, 19; Anthony Freeman, 18; and Steven Booker, 19; drowned after a boat used to transport them across the lake, which was also occupied by three officers, capsized less than 100 feet from shore. Two police officers and one probation officer who had been in the boat were tried for the offense of criminally negligent homicide, but all were acquitted by a jury in Dallas.[14]

Mexia also made news when its former resident Anna Nicole Smith died,[15] and when Allen Stanford was arrested on allegations of fraud in 2009.[5]

The city of Mexia, the confusion over its correct pronunciation and the city motto are all the subject of an Act 1 Aria in Mark-Anthony Turnage's Opera Anna Nicole staged by the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London. Various imagined residents such as the Town Mayor and head of the Chamber of Commerce also feature alongside of the Operas namesake.

Education

[edit]Mexia is zoned to schools in the Mexia Independent School District.[16]

Schools include:

- A.B. McBay Elementary School

- R.Q. Sims Intermediate School

- Mexia Junior High School

- Mexia High School

Pre-integration:

- Woodland High School (African-American)

- Paul Lawrence Dunbar High School (African-American)[17]

Post-Secondary Education:

- Navarro College's Mexia Campus

Notable people

[edit]- Les Baxter, musician and composer

- Kelvin Beachum, NFL offensive lineman

- Quentin Durward Corley, judge

- Bill Crider, novelist

- W. C. Friley, clergyman and educator

- Henry Cecil McBay, chemist

- Ynés Mexía, botanist

- Washington Phillips, singer

- Ray Rhodes, NFL player and coach

- Anna Nicole Smith, model and actress

- Daniel Wayne Smith, son of Anna Nicole Smith

- Allen Stanford, financier, convicted felon

- Lee Wilder Thomas, oilman

- Cindy Walker, songwriter and singer

Climate

[edit]The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Mexia has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[18]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Mexia, Texas

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Texas Almanac Pronunciation Guide" (PDF). Texas Almanac. Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 24, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

Mexia — muh HĀ uh

- ^ a b Alderson, Andrew; Philip Sherwell; Patrick Sawer (February 21, 2009). "Sir Allen Stanford: how the small-town Texas boy evaded scrutiny to become a big-time 'fraudster'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ https://www.census.gov/ [not specific enough to verify]

- ^ "About the Hispanic Population and its Origin". www.census.gov. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ^ A Memorial and Biographical History of Navarro, Henderson, Anderson, Limestone, Freestone and Leon Counties, Texas. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company. 1893. p. 358. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- ^ Matson, George (1916). "GAS PROSPECTS SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST OF DALLAS, in NATURAL GAS RESOURCES OF PARTS OF NORTH TEXAS, USGS Bulletin 629" (PDF). USGS. p. 88. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ Olien, Diana; Olien, Roger (2002). Oil in Texas, The Gusher Age, 1895-1945. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 118–125. ISBN 0292760566.

- ^ Smyrl, Vivian Elizabeth. "Mexia, TX". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ a b Coleman, Jonathan (June 22, 2001). "Juneteenth". The Texas Observer. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ Brown, Angela K. (February 9, 2007). "Some in Smith's Hometown Not So Warm". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ "Mexia Independent School District". Archived from the original on July 13, 2009. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ Gosselin, Rick (November 6, 1995). "Nothing less than the best: Rhodes always expect to win". The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved June 16, 2009.

- ^ Climate Summary for Mexia, Texas