Pannonian Avars

Avar Khaganate | |

|---|---|

| 567 – 822[1] | |

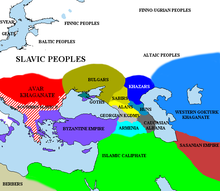

The Avar Khaganate ( ) and main contemporary polities c. 576 | |

The Avar Khaganate and surroundings c. 602. | |

| Common languages |

|

| Religion | Originally shamanism and animism, Christianity after 796 |

| Government | Khanate |

| Khagan | |

| History | |

• Established | 567 |

• Defeated by Pepin of Italy | 796 |

• Disestablished | 822[1] |

The Pannonian Avars (/ˈævɑːrz/ AV-arz) were an alliance of several groups of Eurasian nomads of various origins.[8] The peoples were also known as the Obri in chronicles of Rus, the Abaroi or Varchonitai[9] (Greek: Βαρχονίτες, romanized: Varchonítes), or Pseudo-Avars[10] in Byzantine sources, and the Apar (Old Turkic: 𐰯𐰺) to the Göktürks (Kultegin Inscription: Apar – Avars were called "Apar"). They established the Avar Khaganate, which spanned the Pannonian Basin and considerable areas of Central and Eastern Europe from the late 6th to the early 9th century.[11]

The name Pannonian Avars (after the area in which they settled) is used to distinguish them from the Avars of the Caucasus, a separate people with whom the Pannonian Avars may or may not have had links. Although the name Avar first appeared in the mid-5th century, the Pannonian Avars entered the historical scene in the mid-6th century,[12] on the Pontic–Caspian steppe as a people who wished to escape the rule of the Göktürks. They are probably best known for their invasions and destruction in the Avar–Byzantine wars from 568 to 626 and influence on the Slavic migrations to Southeastern Europe.

Recent archaeogenetic studies indicate that the Pannonian Avars were of primarily Ancient Northeast Asian ancestry similar to those of modern-day people from Mongolia and the Amur River region in Manchuria, pointing to an initial rapid migration of nomadic tribes into the centre of Europe from the Eastern Eurasian Steppe. The Pannonian Avars' core may have been descended from the remnants of the Rouran Khaganate, which were accompanied by other Steppe groups.[13][14][15][16][17][18][note 1] Linguistic evidence suggests that the later Avar population shifted to Slavic as lingua franca.[19][20][21]

Origins

[edit]Avars and pseudo-Avars

[edit]The earliest clear reference to the Avar ethnonym comes from Priscus the Rhetor (420s–after 472), who recounts that in c. 463 the Šaragurs and Onogurs were attacked by the Sabirs, who had been attacked by the Avars. In turn, the Avars had been driven off by people fleeing "man-eating griffins" coming from "the ocean" (Priscus Fr 40).[22] Whilst Priscus' accounts provide some information about the ethno-political situation in the Don-Kuban-Volga region after the demise of the Huns, no unequivocal conclusions can be reached. Denis Sinor has argued that whoever the "Avars" referred to by Priscus were, they differed from the Avars who appear a century later, during the time of Justinian (r. 527–565).[23]

The next author to discuss the Avars, Menander Protector, appeared during the 6th century and wrote of Göktürk embassies to Constantinople in 565 and 568. The Turks appeared angry at the Byzantines for having made an alliance with the Avars, whom the Turks saw as their subjects and slaves. Turxanthos, a Turk prince, calls the Avars "Varchonites" and "escaped slaves of the Turks", who numbered "about 20 thousand" (Menander Fr 43).[24]

Many more, but somewhat confusing, details come from Theophylact Simocatta, who in c. 629, describes the final two decades of the 6th century. In particular, he claims to quote a triumph letter from Turxanthos:

For this very Chagan had in fact outfought the leader of the nation of the Abdali (I mean indeed, of the Hephthalites, as they are called), conquered him, and assumed the rule of the nation. Then he […] enslaved the Avar nation.

But let no one think that we are distorting the history of these times because he supposes that the Avars are those barbarians neighbouring on Europe and Pannonia, and that their arrival was prior to the times of the emperor Maurice. For it is by a misnomer that the barbarians on the Ister have assumed the appellation of Avars; the origin of their race will shortly be revealed.

So, when the Avars had been defeated (for we are returning to the account) some of them made their escape to those who inhabit Taugast. Taugast is a famous city, which is a total of one thousand five hundred miles distant from those who are called Turks, ... Others of the Avars, who declined to humbler fortune because of their defeat, came to those who are called Moukri (Goguryeo); this nation is the closest neighbour to the men of Taugast;

Then the Chagan embarked on yet another enterprise, and subdued all the Ogur, which is one of the strongest tribes on account of its large population and its armed training for war. These make their habitations in the east, by the course of the Til, which Turks are accustomed to call Melas. The earliest leaders of this nation were named Var and Chunni; from them some parts of those nations were also accorded their nomenclature, being called Var and Chunni.

Then, while the emperor Justinian was in possession of the royal power, a small section of these Var and Chunni fled from that ancestral tribe and settled in Europe. These named themselves Avars and glorified their leader with the appellation of Chagan. Let us declare, without departing in the least from the truth, how the means of changing their name came to them. […]

When the Barsils, Onogurs, Sabirs, and other Hun nations in addition to these, saw that a section of those who were still Var and Chunni had fled to their regions, they plunged into extreme panic, since they suspected that the settlers were Avars. For this reason they honoured the fugitives with splendid gifts and supposed that they received from them security in exchange.

Then, after the Var and Chunni saw the well-omened beginning to their flight, they appropriated the ambassadors' error and named themselves Avars: for among the Scythian nations that of the Avars is said to be the most adept tribe. In point of fact even up to our present times the Pseudo-Avars (for it is more correct to refer to them thus) are divided in their ancestry, some bearing the time-honoured name of Var while others are called Chunni.

According to the interpretation of Dobrovits and Nechaeva, the Turks insisted that the Avars were only "pseudo-Avars", so as to boast that they were the only formidable power in the Eurasian steppe. The Göktürks claimed that the "real Avars" remained loyal subjects of the Turks, farther east.[23][26] A political name *(A)Par 𐰯𐰻 was indeed mentioned in inscriptions honoring Kul Tigin and Bilge Qaghan, yet in Armenian sources (Egishe Vardapet, Ghazar Parpetsi, and Sebeos) Apar seemingly indicated "a geographical area (Khorasan), which might also intimate a political formation once there"; additionally, "'Apar-shar', that is, the country of the Apar" was named after possibly Hephthalites, who were known as 滑 MC *ɦˠuɛt̚ > Ch.Huá in Chinese sources. Even so, *Apar could not be linked to the European Avars, notwithstanding any link, if there were, between the Hephthalites and Rourans.[27][page needed] Furthermore, Dobrovits has questioned the authenticity of Theophylact's account. As such, he has argued that Theophylact borrowed information from Menander's accounts of Byzantine–Turk negotiations to meet political needs of his time – i.e. to castigate and deride the Avars during a time of strained political relations between the Byzantines and Avars (coinciding with Emperor Maurice's northern Balkan campaigns).[23]

Paul the Deacon

[edit]Paul the Deacon in his History of the Lombards insisted that Avars were known previously as Huns and he conflated the two groups.[28]

Uar, Rouran and other Central Asian peoples

[edit]According to some scholars, the Pannonian Avars originated from a confederation formed in the Aral Sea region, by the Uar (also known as the Ouar, Warr or Var) and the Xionites.[29][page needed][30] The Xionites had likely been speakers of Iranian and/or Turkic languages.[31] The Hephthalites, affiliated previously to the Uar and Xionites, had remained in Central and northern South Asia. The Pannonian Avars were also known by names including Uarkhon or Varchonites – which may have been a portmanteau combining Var and Chunni.

The 18th-century historian Joseph de Guignes postulates a link between the Avars of European history with the Rouran Khaganate of Inner Asia based on a coincidence between Tardan Khan's letter to Constantinople and events recorded in Chinese sources, notably the Wei Shu and Bei Shi.[32] Chinese sources state that Bumin Qaghan, founder of the First Turkic Khaganate, defeated the Rouran, some of whom fled and joined the Western Wei. Later, Bumin's successor Muqan Qaghan defeated the Hephthalites as well as the Turkic Tiele. Superficially these victories over the Tiele, Rouran and Hephthalites echo a narrative in the Theophylact, boasting of Tardan's victories over the Hephthalites, Avars and Oghurs. However, the two series of events are not synonymous: the events of the latter took place during Tardan's rule, c. 580–599, whilst Chinese sources referring to the Turk defeat of the Rouran and other Central Asian peoples occurred 50 years earlier, at the founding of the First Turkic Khaganate. It is for this reason that the linguist János Harmatta rejected the identification of the Avars with the Rouran on this basis.

According to Edwin G. Pulleyblank, the name Avar is the same as the prestigious name Wuhuan in the Chinese sources.[33] Several historians, including Peter Benjamin Golden, suggest that the Avars are of Turkic origin, likely from the Oghur branch.[34] Another theory suggests that some of the Avars were of Tungusic origin.[3] A study by Emil Heršak and Ana Silić (2002) suggests that the Avars were of heterogeneous origin, including mostly Turkic (Oghuric) and Mongolic groups. Later in Europe some Germanic and Slavic groups were assimilated into the Avars. Heršak and Silić concluded that their exact origin is unknown but stated that it is likely that the Avars were originally mainly composed of Turkic (Oghuric) tribes.[35][page needed]

Increasing evidence supports a relationship between the elite of the Pannonian Avars and the Inner Asian Rouran Khaganate; however it remains unclear to what extent the European Avars descent from the Rouran population. It is argued that the initial elite core of the Pannonian Avars spoke a Para-Mongolic language (Serbi-Avar), which is a sister lineage to contemporary Mongolic languages.[36][37]

Steppe empire dynamics and ethnogenesis

[edit]

In 2003, Walter Pohl summarized the formation of nomadic empires:[38]

1. Many steppe empires were founded by groups who had been defeated in previous power struggles but had fled from the dominion of the stronger group. The Avars were likely a losing faction previously subordinate to the (legitimate)[clarification needed] Ashina clan in the Western Turkic Khaganate, and they fled west of the Dnieper.

2. These groups usually were of mixed origin, and each of its components was part of a previous group.

3. Crucial in the process was the elevation of a khagan, which signified a claim to independent power and an expansionist strategy. This group also needed a new name that would give all of its initial followers a sense of identity.

4. The name for a new group of steppe riders was often taken from a repertoire of prestigious names which did not necessarily denote any direct affiliation to or descent from groups of the same name; in the Early Middle Ages, Huns, Avars, Bulgars, and Ogurs, or names connected with -(o)gur (Kutrigurs, Utigurs, Onogurs, etc.), were most important. In the process of name-giving, both perceptions by outsiders and self-designation played a role. These names were also connected with prestigious traditions that directly expressed political pretensions and programmes, and had to be endorsed by success. In the world of the steppe, where agglomerations of groups were rather fluid, it was vital to know how to deal with a newly-emergent power. The symbolical hierarchy of prestige expressed through names provided some orientation for friend and foe alike.

Such views are mirrored by Csanád Bálint. "The ethnogenesis of early medieval peoples of steppe origin cannot be conceived in a single linear fashion due to their great and constant mobility", with no ethnogenetic "point zero", theoretical "proto-people" or proto-language.[39][page needed] Moreover, Avar identity was strongly linked to Avar political institutions. Groups who rebelled or fled from the Avar realm could never be called "Avars", but were rather termed "Bulgars". Similarly, with the final demise of Avar power in the early 9th century, Avar identity disappeared almost instantaneously.[40][page needed]

Savelyev and Jeong (2020) in "Early nomads of the Eastern Steppe and their tentative connections in the West" concluded that the initial Pannonian Avars formed in Central Asia from various ethno-linguistic groups, including Iranian peoples, Ugrians, Oghur-Turks, and Rouran tribes. They further note that "the broadly East Asian component in the archaeological record of the European Avars is limited even in the earlier period of their history; elements originating from West Asia, the Caucasus, the Southern Russian steppes and the local Central European cultures can be traced alongside each other".[41]

Subsequent analyses from 2022 on Avar remains however confirmed their Ancient Northeast Asian origin, and support a possible ethnogenesis of the Avar Elite from the former Rouran Khaganate.[42][43]

Anthropology

[edit]In the Stuttgart Psalter there is an image of mounted archers riding backwards on their horses, a noted "Asian" tactic, which may depict the Avars.[44] According to mid-20th century physical anthropologists such as Pál Lipták, human remains from the early Avar (7th century) period had mostly "Europoid" features, while grave goods indicated cultural links to the Eurasian Steppe.[45] Cemeteries dated to the late Avar period (8th century) included many human remains with physical features typical of East Asian people or Eurasians (i.e., people with both East Asian and European ancestry).[46] Remains with East Asian or Eurasian features were found in about one third of the Avar graves from the 8th century.[47] According to Lipták, 79% of the population of the Danube-Tisza region during the Avar period showed Europoid characteristics.[45] However, Lipták used racial terms later deprecated or regarded as obsolete, such as "Mongoloid" for northeast Asian and "Turanid" for individuals of mixed ancestry.[48][page needed] Several theories suggest that the ruling class of the Avars were of Northern East Asian origin resembling the "Tungid type" (common among Tungusic speaking peoples).[3]

Archaeogenetics

[edit]

A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in September 2016 examined the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of 31 people buried in the Carpathian Basin between the 7th and 9th centuries.[50] They were found to be mostly carrying European haplogroups such as H, K, T and U, while about 15% carried Asian haplogroups such as C, M6, D4c1 and F1a.[51] Their mtDNA were found to be primarily characteristic of Eastern and Southern Europe.[52]

A genetic study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in 2018 examined 62 individuals buried in the 8th and 9th centuries at an Avar-Slavic burial in Cífer‐Pác, Slovakia.[53] Of the 46 samples of mtDNA extracted, 93% belonged to west Eurasian lineages, while 6% belonged to east Eurasian lineages.[54] The amount of east Eurasian lineages was higher than among modern European populations, but lower than what has been found in other genetic studies on the Avars.[55] The mtDNA of the examined individuals was found to be quite similar to medieval and modern Slavs, and it was suggested that the mixed population examined had emerged through intermarriage between Avar males and Slavic females.[56]

A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in November 2019 examined the remains of fourteen Avar males. Eleven of them were dated to the early Avar period, and three were dated to the middle and late Avar period.[57] The eleven early Avar males were found to be carrying the paternal haplogroups N1a1a1a1a3 (four samples), N1a1a (two samples), R1a1a1b2a (two samples), C2, G2a, and I1.[57] The three males dated to the middle and late Avar period carried the paternal haplogroups C2, N1a1a1a1a3 and E1b1b1a1b1a.[57] In short, most carried "East Eurasian Y haplogroups typical for modern north-eastern Siberian and Buryat populations". The Avars studied were all determined to have had dark eyes and dark hair, and the majority of them were found to be primarily of East Asian origin.[58]

A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in January 2020 examined the remains of 26 individuals buried at various elite Avar cemeteries in the Pannonian Basin dated to the 7th century.[59] The mtDNA of these Avars belonged mostly to East Asian haplogroups, while the Y-DNA was exclusively of East Asian origin and "strikingly homogenous", belonging to haplogroups N-M231 and Q-M242.[60] The evidence suggests that the Avar elite were largely patrilineal and endogamous for a period of around one century, and entered the Pannonian Basin through migrations from East Asia involving both men and women.[61] Another 2020 study, but of Xiongnu remains in East Asia, found that the Xiongnu shared certain paternal (N1a, Q1a, R1a-Z94 and R1a-Z2124) and maternal haplotypes with the Huns and Avars, and suggested on this basis that they were descended from Xiongnu, who they in turn suggested were descended from Scytho-Siberians.[62]

A genetic study published in scientific journal Cell in April 2022 analyzed 48 Pannonian Avar samples from the early, middle and late period, and found nearly all of them to have a high level of Ancient Northeast Asian (ANA) ancestry. The paternal lineage N1a1a1a1a3a-F4205 was most common (today highest percent of haplogroup N-F4205 was found in Dukha people of Mongolia with 52.2%[63]), with Q1a, Q1b, R1a, R1b and E1b subclades present in smaller numbers. The samples had a strong affinity with modern peoples inhabiting the region from Mongolia to the Amur, with a historical Rouran Khaganate sample, and with samples from Xiongnu-Xianbei periods in the eastern Asian steppe.[42] The Avar individuals showed their highest genetic affinity with present-day Mongolic and Tungusic peoples, as well as Nivkhs.[43]

A genetic study published in scientific journal Current Biology in May 2022 examined 143 Avar samples from various periods, including Avar elites and local commoners. It confirmed the Ancient Northeast Asian (ANA) paternal and maternal origin for the Avar elite, with N1a-F4205 being their predominant and characteristic paternal lineage, alongside incorporated Q1a2a1 and R1a-Z94 Hunnic-Iranian remnants, and the rest belonging to local haplogroups found among surrounding populations. Autosomally, the Elite Avar samples "preserved very ancient Mongolian pre-Bronze Age genomes, with ca 90% [Ancient North-East Asian] ancestry", shared deep ancestry with European Huns, but although since Early Avar period started mixing with local and immigrant Hunnic-Iranian related populations, "people with different genetic ancestries were seemingly distinguished, as samples with Hun-related genomes were buried in separate cemeteries". The majority of the Avar Khaganate general population consisted of local European peoples (EU_core) but did not display Northeast Asian admixture, supporting a model of elite dominance of arriving horse nomads over a large sedentary population, with at least some subsequent admixture events. Genetic data on later Avar elite samples showed continuity with earlier Avars and the long-term presence of Northeast Asian ancestry among the Avar elite, suggesting a possible endogamous social system. There was however an increase of Northeast Asian and Saka associated ancestry among the total population, suggesting either further migration from the Eurasian Steppe and admixture between local and Avar groups, or substructure among the overall population not observed before.[16]

History

[edit]Arrival in Europe

[edit]In 557, the Avars sent an embassy to Constantinople, presumably from the northern Caucasus. This marked their first contact with the Byzantine Empire. In exchange for gold, they agreed to subjugate the "unruly gentes" on behalf of the Byzantines: subsequently they conquered and incorporated various nomadic tribes—Kutrigurs and Sabirs—and defeated the Antes.

Pohl 1998, p. 18: [...] the first thing the Avars did when they came near the Caucasus on their flight from Central Asia was to send an embassy to the aging emperor Justinian. That took place sometime in winter 558/59, and they struck the usual deal: the Avars were to fight for the Empire against unruly gentes and in turn would receive annual payments and other benefits. Indeed, for 20 years to come the Avars, under their Khagan Baian, fought Utigurs and Antes, Gepids and Slavs, whereas their policy towards the Empire relied more on negotiation than on war."

By 562 the Avars controlled the lower Danube basin and the steppes north of the Black Sea.[64][need quotation to verify] By the time they arrived in the Balkans, the Avars formed a heterogeneous group of about 20,000 horsemen.[65] After the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I bought them off, they pushed northwestwards into Germania. However, Frankish opposition halted the Avars' expansion in that direction. Seeking rich pastoral lands, the Avars initially demanded land south of the Danube in present-day Bulgaria, but the Byzantines refused, using their contacts with the Göktürks as a threat against Avar aggression.[66] The Avars turned their attention to the Carpathian Basin and to the natural defenses it afforded.[67] The Carpathian Basin was occupied by the Gepids. In 567 the Avars formed an alliance with the Lombards—enemies of the Gepids—and together they destroyed much of the Gepid kingdom. The Avars then persuaded the Lombards to move into northern Italy, an invasion that marked the last Germanic mass-movement in the Migration Period.[citation needed]

Continuing their successful policy of turning the various barbarians against each other, the Byzantines persuaded the Avars to attack the Sclavenes in Scythia Minor, a land rich with goods.[65][page needed] After devastating much of the Sclavenes' land, the Avars returned to Pannonia after many of the khagan's subjects deserted to the Byzantine emperor.

Early Avar period (580–670)

[edit]

By about 580, the Avar Khagan Bayan I had established supremacy over most of the Slavic, Germanic and Bulgar tribes living in Pannonia and the Carpathian Basin.[64] When the Byzantine Empire was unable to pay subsidies or hire Avar mercenaries, the Avars raided their Balkan territories. According to Menander, Bayan I commanded an army of 10,000 Kutrigur Bulgars and sacked Dalmatia in 568, effectively cutting the Byzantine terrestrial link with northern Italy and western Europe.

In the 580s and 590s, many of the imperial armies were busy fighting the Persians, and the remaining troops in the Balkans were no match for the Avars.[68] By 582, the Avars had captured Sirmium, an important fort in Pannonia. When the Byzantines refused to increase the stipend amount as requested by Bayan's son and successor Bayan II, the Avars proceeded to capture Singidunum (Belgrade) and Viminacium. They suffered setbacks, however, during Maurice's Balkan campaigns in the 590s.

By 600 the Avars had established a nomadic empire ruling over a multitude of peoples and stretching from modern Austria in the west to the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the east.[citation needed] After being defeated at the Battles of Viminacium in their homeland, some Avars defected to the Byzantines in 602, but Emperor Maurice decided not to return home as was customary.[69] He maintained his army camp beyond the Danube throughout the winter, but the hardship caused the army to revolt, giving the Avars a desperately needed respite and they attempted an invasion of northern Italy in 610. The Byzantine civil war prompted a Persian invasion in the Byzantine–Sasanian War, and after 615 the Avars enjoyed a free hand in the undefended Balkans.

While negotiating with Emperor Heraclius beneath the walls of Constantinople in 617, the Avars launched a surprise attack. While they were unable to capture the city centre, they pillaged the suburbs and took 270,000 captives. Payments in gold and goods to the Avars reached a sum of 200,000 solidi shortly before 626.[70][page needed] In 626, the Avars cooperated with the Sassanid force in the failed siege of 626. Following this defeat, the political and military power of the Avars declined. Byzantine and Frankish sources documented a war between the Avars and their western Slav clients, the Wends.[65]

Each year, the Huns [Avars] came to the Slavs, to spend the winter with them; then they took the wives and daughters of the Slavs and slept with them, and among the other mistreatments [already mentioned] the Slavs were also forced to pay levies to the Huns. But the sons of the Huns, who were [then] raised with the wives and daughters of these Wends could not finally endure this oppression anymore and refused obedience to the Huns and began, as already mentioned, a rebellion. When now the Wendish army went against the Huns, the [aforementioned] merchant Samo accompanied the same. And so Samo's bravery proved itself in wonderful ways and a huge mass of Huns fell to the sword of the Wends.

— Chronicle of Fredegar, Book IV, Section 48, written c. 642

In the 630s, Samo, the ruler of the first Slavic polity known as Samo's Tribal Union or Samo's realm, increased his authority over lands to the north and west of the Khaganate at the expense of the Avars, ruling until his death in 658.[71] The Chronicle of Fredegar records that during Samo's rebellion in 631, 9,000 Bulgars led by Alciocus left Pannonia to modern-day Bavaria where Dagobert I massacred most of them. The remaining 700 joined the Wends.

At about the time of Samo's realm, Bulgar leader Kubrat of the Dulo clan led a successful uprising to end Avar authority over the Pannonian Plain, establishing Old Great Bulgaria, or Patria Onoguria, "the homeland of Onogurs". The civil war, possibly a succession struggle in Onoguria between the Kutrigurs under Alciocus on one side and Utigur forces on the other, raged from 631 to 632. After Alciocus fled to Bavaria, the power of the Avars' Kutrigur forces was shattered, and Kubrat established peace between the Avars and Byzantium in 632. According to Constantine VII's 10th century work De Administrando Imperio, a group of Croats who had separated from the White Croats in White Croatia had also fought against the Avars, after which they organized the Duchy of Croatia.[72] The Unknown Archon's people from Samo's realm were also resettled at this time.

Middle (670–720) and late (720–822) Avar periods

[edit]

With the death of Samo in 658 and Kubrat in 665, some Slavic tribes again came under Avar rule. Despite their father's advice, Kubrat's sons failed to maintain cohesion in Old Great Bulgaria which began to disintegrate. A few years later in the time of Batbayan, Old Great Bulgaria dissolved into five branches. From western Onoguria the first group of folk moved to Ravenna under Alzeco in the 650s. According to Book II of the Miracles of Saint Demetrius, a certain Avar Chagan seized his opportunity to coalesce in the regions further north in response to the secession of the Diocese of Sirmium in the 670s by a "Kuber" Chagan.

- "Finally, the (Avar) Chagan, considering them to constitute a people with an identity of its own put, in accordance to the custom of his race, a chieftain upon them, a man by the name of Kouver. When Kouver (Chagan) learned from some of his most intimate associates the desire of the exiled Romans for their ancestral homes, he gave the matter some thought, then took them together with other peoples, i.e., the foreigners who had joined them, [as is said in the Book of Moses about the Jews at the time of their exodus,] with all their baggage and arms. According to what is said, they rebelled and separated themselves from the (Avar) Chagan. The (Avar) Chagan, when he learned this, set himself in pursuit of them, met them in five or six battles and, being defeated in each one by them, took flight and retired to the regions further north. After the victory, Kouver (Chagan), together with the aforementioned people, crossed the aforementioned river Danube, came to our regions and occupied the Keramesion plain."[73]

About this time, Mark of Kalt records that in 677, the principality of Ungvar (Ung fortress) was established in the regions further north where Kotrag's group also fled following the chaos, and a third group of Onogur-Bulgarians led by Batayan was subdued by Ziebel's emerging Khazar Empire according to Nikephoros I of Constantinople. Under Mauros, a fourth group of folk eventually settled in the present-day region of North Macedonia. The fifth group from Onogur, Bulgaria, led by Khan Asparukh—the father of Khan Tervel—settled permanently along the Danube (c. 679–681), establishing the First Bulgarian Empire, stabilized by the victory at the battle of Ongal south of the eastern Carpathians. The Bulgarians turned on Byzantium who had established an alliance with Ziebel's Khazars.

Although the Avar empire had diminished to half its original size, the Avar-Slav alliance consolidated their rule west from the central parts of the mid-Danubian basin and extended their sphere of influence west to the Vienna Basin. The new ethnic element marked by hair clips for pigtails; curved, single-edged sabres; and broad, symmetrical bows marks the middle Avar-Bulgar period (670–720). New regional centers, such as those near Ozora and Igar appeared. This strengthened the Avars' power base, although most of the Balkans lay in the hands of Slavic tribes since neither the Avars nor Byzantines were able to reassert control.[citation needed]

There are very few sources that cover the last century of Avar history. They only talk about the relations between the Avars and Lombards but little about the internals of the khaganate, so information about the Carpathian Basin is mostly from archaeology. Even here, elites are almost invisible, and there is little evidence of nomadic behavior. This transformation is little understood, but may have something to do with population growth.[74]

A new type of ceramics—the so-called "Devínska Nová Ves" pottery—emerged at the end of the 7th century in the region between the Middle Danube and the Carpathians.[75] These vessels were similar to the hand-made pottery of the previous period, but wheel-made items were also found in Devínska Nová Ves sites.[75] Large inhumation cemeteries found at Holiare, Nové Zámky and other places in Slovakia, Hungary and Serbia from the period beginning around 690 show that the settlement network of the Carpathian Basin became more stable in the Late Avar period.[75][76] The most popular Late Avar motifs—griffins and tendrils decorating belts, mounts and a number of other artifacts connected to warriors—may either represent nostalgia for the lost nomadic past or evidence a new wave of nomads arriving from the Pontic steppes at the end of the 7th century.[77][78] According to historians who accept the latter theory, the immigrants may have been either Onogurs[79] or Alans.[80] Anthropological studies of the skeletons point at the presence of a population with mongoloid features.[77]

The Khaganate in the Middle and Late periods was a product of cultural symbiosis between Slavic and original Avar elements with a Slavic language as a lingua franca or the most common language.[2] In the 7th century, the Avar Khaganate opened a door for Slavic demographic and linguistic expansion to Adriatic and Aegean regions (see Slavic migrations to Southeastern Europe).

In the early 8th century, a new archaeological culture—the so-called "griffin and tendril" culture—appeared in the Carpathian Basin. Some theories, including the "double conquest" theory of archaeologist Gyula László, attribute it to the arrival of new settlers, such as early Magyars, but this is still under debate. Hungarian archaeologists Laszló Makkai and András Mócsy attribute this culture to an internal evolution of Avars resulting from the integration of the Bulgar émigrés from the previous generation of the 670s. According to Makkai and Mócsy, "the material culture—art, clothing, equipment, weapons—of the late Avar/Bulgar period evolved autonomously from these new foundations". Many regions that had once been important centers of the Avar Empire had lost their significance while new ones arose. Although Avaric material culture found over much of the northern Balkans may indicate an existing Avar presence, it probably represents the presence of independent Slavs who had adopted Avaric customs.[67] Radovan Bunardžić dated Avar-Bulgar graves excavated in Čelarevo (near Sirmium), containing skulls with Mongolian features and Judaic symbols, to the late 8th century and 9th century.[81]

Collapse

[edit]

The gradual decline of Avar power accelerated to a rapid fall. A series of Frankish campaigns, beginning from 788, ended with the conquest of the Avar realm within a decade. Initial conflict between Avars and Franks occurred soon after the Frankish deposition of Bavarian duke Tassilo III and the establishment of direct Frankish rule over Bavaria in 788. At that time, the border between Bavarians and Avars was situated on the river Enns. An initial Avarian incursion into Bavaria was repelled, and Franco-Bavarian forces responded by taking the war to neighbouring Avarian territories, situated along the Danube, east of Enns. The two sides collided near the river Ybbs, on Ybbs Field (German: Ybbsfeld), where the Avars suffered a defeat in 788. This heralded the rise of Frankish power and Avarian decline in the region.[82][83]

In 790, the Avars tried to negotiate a peace settlement with the Franks, but no agreement was reached.[83] A Frankish campaign against the Avars, initiated in 791, ended successfully for the Franks. A large Frankish army, led by Charlemagne, crossed from Bavaria into the Avarian territory beyond the Enns, and started to advance along the Danube in two columns, but found no resistance and soon reached the region of the Vienna Woods, near the Pannonian Plain. No pitched battle was fought,[84] since the Avars had fled before the advancing Carolingian army, while disease left most of the Avar horses dead.[84] Tribal infighting began, showing the weakness of the khaganate.[84]

The Franks had been supported by the Slavs, who established polities on former Avar territory.[85] Charlemagne's son Pepin of Italy captured a large, fortified encampment known as "the Ring", which contained much of the spoils from earlier Avar campaigns.[86] The campaign against the Avars again gathered momentum. By 796, the Avar chieftains had surrendered and became open to the acceptance of Christianity.[84] In the meantime, all of Pannonia was conquered.[87] According to the Annales Regni Francorum, the Avars began to submit to the Franks in 796. The song "De Pippini regis Victoria Avarica" celebrating the defeat of the Avars at the hands of Pepin of Italy in 796 still survives. The Franks baptized many Avars and integrated them into the Frankish Empire.[88] In 799, some Avars revolted.[89]

In 804, Bulgaria conquered the southeastern Avar lands in Transylvania and southeastern Pannonia up to the Middle Danube, and many Avars became subjects of the Bulgarian Empire. Khagan Theodorus, a convert to Christianity, died after asking Charlemagne for help in 805; he was succeeded by Khagan Abraham, who was baptized as the new Frankish client (and should not be assumed from his name alone to have been Khavar rather than Pseudo-Avar). Abraham was succeeded by Khagan (or Tudun) Isaac (Latin Canizauci), about whom little is known. The Franks turned the Avar lands under their control into a frontier march. The March of Pannonia—the eastern half of the Avar March—was then granted to the Slavic Prince Pribina, who established the Lower Pannonia principality in 840.

Whatever was left of Avar power was effectively ended when the Bulgars expanded their territory into the central and eastern portions of traditional Avar lands around 829.[90] According to Pohl, an Avar presence in Pannonia is certain in 871, but thereafter the name is no longer used by chroniclers. Pohl wrote, "It simply proved impossible to keep up an Avar identity after Avar institutions and the high claims of their tradition had failed",[91] although Regino wrote about them in 889.[92][93] The growing amount of archaeological evidence in Transdanubia also presumes an Avar population in the Carpathian Basin in the late 9th century.[92] Archaeological findings suggest a substantial, late Avar presence on the Great Hungarian Plain; however, it is difficult to determine their proper chronology.[92] The preliminary results of the new excavations also imply that the known and largely accepted theory of the destruction of the Avar settlement area is outdated; a disastrous depopulation of the Avar Khaganate never happened.[94][page needed]

Byzantine records, including the "Notitia episcopatuum", the "Additio patriarchicorum thronorum" by Neilos Doxapatres, the "Chronica" by Petrus Alexandrinus and the "Notitia patriarchatuum" mention the 9th century Avars as an existing Christian population.[92] The Avars had already been mixing with the more numerous Slavs for generations, and they later came under the rule of external polities, such as the Franks, Bulgaria, and Great Moravia.[95] Fine presumes that Avar descendants who survived the Hungarian Conquest in the 890s were likely absorbed by the Hungarian population.[95] After the mid to late 8th-century Frankish conquest of Pannonia, Avar and Bulgar refugees migrated to settle in the area of Bulgaria and along its western periphery.[96] The Avars in the region known as solitudo avarorum—currently called the Great Hungarian Plain—vanished in an arc of three generations. They slowly merged with the Slavs to create a bilingual Turkic-Slavic-speaking people who were subjected to Frankish domination; the invading Magyars found this composite people in the late 9th century.[97] The De Administrando Imperio, written around 950 and based on older documents, states that "there are still descendants of the Avars in Croatia, and are recognized as Avars". Modern historians and archaeologists until now proved the opposite, that Avars never lived in Dalmatia proper (including Lika), that statement occurred somewhere in Pannonia, and the information belongs to the 9th century.[98][99] There has been speculation that the modern Avar people of the Caucasus might have an uncertain connection to the historical Avars, but direct descent from them is rejected or doubted by many scholars.[90]

List of known khagans

[edit]The recorded Avar khagans were:[100]

- Shaush (? – c. 552)

- Kandik (c. 552 – c. 562)

- Bayan I (562–602)

- Bayan II (602–617)

- Bayan III (617–630)

- Kouver Chagan (677–?)

- Theodorus (795–805)

- Abraham (805–?)

- Isaac (?–835)

Social and tribal structure

[edit]

The Pannonian Basin was the centre of the Avar power base. The Avars resettled captives from the peripheries of their empire to more central regions. Avar material culture is found south to Macedonia. However, to the east of the Carpathians, there are next to no Avar archaeological finds, suggesting that they lived mainly in the western Balkans. Scholars propose that a highly structured and hierarchical Avar society existed, having complex interactions with other "barbarian" groups. The khagan was the paramount figure, surrounded by a minority of nomadic aristocracy.

A few exceptionally rich burials have been uncovered, confirming that power was limited to the khagan and a close-knit class of "elite warriors". In addition to hoards of gold coins that accompanied the burials, the men were often buried with symbols of rank, such as decorated belts, weapons, stirrups resembling those found in central Asia, as well as their horse. The Avar army was composed from numerous other groups: Slavic, Gepidic and Bulgar military units. There also appeared to have existed semi-independent "client" (predominantly Slavic) tribes which served strategic roles, such as engaging in diversionary attacks and guarding the Avars' western borders abutting the Frankish Empire.

Initially, the Avars and their subjects lived separately, except for Slavic and Germanic women who married Avar men. Eventually, the Germanic and Slavic peoples were included in the Avaric social order and culture, which was Persian-Byzantine in fashion.[67] Scholars have identified a fused Avar-Slavic culture, characterized by ornaments such as half-moon-shaped earrings, Byzantine-styled buckles, beads, and bracelets with horn-shaped ends.[67] Paul Fouracre notes, "[T]here appears in the seventh century a mixed Slavic-Avar material culture, interpreted as peaceful and harmonious relationships between Avar warriors and Slavic peasants. It is thought possible that at least some of the leaders of the Slavic tribes could have become part of the Avar aristocracy".[101][page needed] Apart from the assimilated Gepids, a few graves of Carolingian peoples have been found in the Avar lands. They perhaps served as mercenaries.[67]

Language

[edit]| Avar | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Avar Khaganate |

| Region | Pannonian Basin |

| Ethnicity | Pannonian Avars |

| Era | 6th-7th centuries |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

The language or languages spoken by the Avars are unknown.[102][103][104][105] Classical philologist Samu Szádeczky-Kardoss states that most of the Avar words used in contemporaneous Latin or Greek texts appear to have their origins in possibly Mongolian or Turkic languages.[106][page needed][107] Other theories propose a Tungusic origin.[3] According to Szádeczky-Kardoss, many of the titles and ranks used by the Pannonian Avars were also used by Turks, Proto-Bulgars, Uighurs and/or Mongols, including khagan (or kagan), khan, kapkhan, tudun, tarkhan, and khatun.[107] There is also evidence, however, that ruling and subject clans spoke a variety of languages. Proposals by scholars include Caucasian,[103] Iranian,[2] Tungusic,[108][page needed][109][page needed][110] Hungarian[citation needed] and Turkic.[9][111] A few scholars speculated that Proto-Slavic became the lingua franca of the Avar Khaganate.[112] Historian Gyula László has suggested that the late 9th-century Pannonian Avars spoke a variety of Old Hungarian, thereby forming an Avar-Hungarian continuity with then-newly arrived Hungarians.[113] Based on archeologic and linguistic data, Florin Curta and Johanna Nichols concluded that there is no convincing evidence for the presence of any Turkic or Mongolic languages among the Avars, but evidence for the presence of Iranian languages, further strengthened by Iranian-derived loanwords and toponyms in the region and among languages within the range of the Avars.[114][page needed]

Shimunek (2017) proposes that the elite core of the Avars spoke a "Para-Mongolic language" of the "Serbi–Awar" group, that is a sister branch of the Mongolic languages. Together, the Serbi–Awar and Mongolic languages make up the Serbi–Mongolic languages.[37]

Warfare

[edit]The Avars were skilled warriors and almost exclusively fought on horseback. They often used light horse archers armed with powerful composite bows, as many other steppe peoples. These archers wore little to no armour, besides occasional helmets or knee guards. The Avars also employed the use of heavy cavalry, fully armoured in chainmail or scale armour as well as helmets. These heavier troops were armed with long lances, swords, and daggers.[115][page needed] Upon subjugating the Slavic tribes in Pannonia, they often allied with the Slavs and employed them as foot soldiers even together laying siege to Constantinople, along with large numbers of Persians. These Slav warriors were usually armed with bows, axes, various types of spears, and round shields.

The Byzantine Emperor Maurice wrote of the Avars and other nomad peoples in the Strategikon:

"They give special attention to training in archery on horseback. A vast herd of male and female horses follows them, both to provide nourishment and to give the impression of a huge army. They do not encamp within entrenchments, as do the Persians and the Romans [Byzantines], but until the day of battle, spread about according to tribes and clans, they continuously graze their horses both summer and winter... Also in the event of battle, when opposed by an infantry force in close formation they stay on their horses and do not dismount, for they do not last long fighting on foot. They have been brought up on horseback, and owing to their lack of exercise they simply cannot walk about on their own feet... "[116][page needed]

— Maurice, Strategikon

Avar-Hungarian continuity theory

[edit]Gyula László suggests that late Avars, arriving to the khaganate in 670 in great numbers, lived through the time between the destruction and plunder of the Avar state by the Franks during 791–795 and the arrival of the Magyars in 895. László points out that the settlements of the Hungarians (Magyars) complemented, rather than replaced, those of the Avars. Avars remained on the plough fields, good for agriculture, while Hungarians took the river banks and river flats, suitable for pasturage. He also notes that while the Hungarian graveyards consist of 40–50 graves on average, those of the Avars contain 600–1,000. According to these findings, the Avars not only survived the end of the Avar polity but lived in great masses and far outnumbered the Hungarian conquerors of Árpád.

He also shows that Hungarians occupied only the centre of the Carpathian basin, but Avars lived in a larger territory. Looking at those territories where only the Avars lived, there are only Hungarian geographical names, not Slavic or Turkic as would be expected interspersed among them. This is further evidence for the Avar-Hungarian continuity. Names of the Hungarian tribes, chieftains and the words used for the leaders, etc., suggest that at least the leaders of the Hungarian conquerors were Turkic speaking. However, Hungarian is not a Turkic language, rather Uralic, and so they must have been assimilated by the Avars that outnumbered them.

László's Avar-Hungarian continuity theory posits that the modern Hungarian language descends from that spoken by the Avars rather than the conquering Magyars.[117][page needed] Based on DNA evidence from graves, the original Magyars most resembled modern Bashkirs, a Turkic people located near the Urals, whereas the Khanty and Mansi, whose languages most resemble Hungarian, live some ways to the northeast of the Bashkirs.[118][119][120]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ it is not unlikely that we can assume that groups from the Western Eurasian steppes took part in the Avar migration, and that at least the Avar khagans and their core group were actually descended from the Rouran. The results of the present article support this view. The written sources also indicate that Cutrigurs, Utigurs and Bulgars from the Pontic steppes accompanied the Avars into the Carpathian Basin.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Waldman & Mason 2006, p. 769.

- ^ a b c Curta 2004, pp. 125–148.

- ^ a b c d Helimski 2004, pp. 59–72.

- ^ de la Fuente 2015.

- ^ Curta 2004, p. 132.

- ^ Some sources claim that Khagan Theodorus and his predecessor Zodan were one and the same; that is, Zodan assumed the name Thedours after converting to Christianity.

- ^ The name of Khagan Isaac appears to have been corrupted into Latin as Canizauci princeps Avarum ("Khagan Isaac, Prince of the Avars").

- ^

- Encyclopædia Britannica & Avar

- Frassetto 2003, pp. 54–55

- Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 46–49

- Beckwith 2009, pp. 390–391: "... the Avars certainly contained peoples belonging to several different ethnolinguistic groups, so that attempts to identify them with one or another specific eastern people are misguided."

- Kyzlasov 1996, p. 322: "The Juan-Juan state was undoubtedly multi-ethnic, but there is no definite evidence as to their language... Some scholars link the Central Asian Juan-Juan with the Avars who came to Europe in the mid-sixth century. According to widespread but unproven and probably unjustified opinion, the Avars spoke a language of the Mongolic group."

- Pritsak 1982, p. 359

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Ukraine & Avars.

- ^ Grousset 1939, p. 171:According to Grousset, Theophylact Simocatta called them pseudo-Avars because he thought the true Avars were the Rouran.

- ^ Pohl 2002, pp. 26–29.

- ^ Curta 2006.

- ^ Neparáczki & Maróti 2019.

- ^ Csáky & Gerber 2020.

- ^ Gnecchi-Ruscone et al. 2022.

- ^ a b Maróti, Neparáczki & Schütz 2022.

- ^ David 2022.

- ^ Saag & Staniuk 2022, pp. 38–41.

- ^ Curta, Florin (2004). "The Slavic lingua franca (Linguistic notes of an archaeologist turned historian)". East Central Europe/L'Europe du Centre-Est. 31: 125–148. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Wihoda, Martin (2021-10-27), "After Avars: The Beginning of the Ruling Power on the Eastern Fringe of Carolingian Empire", Rulership in Medieval East Central Europe, Brill, pp. 63–80, ISBN 978-90-04-50011-2, retrieved 2024-01-16

- ^ Rady, Martyn (2020), Curry, Anne; Graff, David A. (eds.), "The Slavs, Avars, and Hungarians", The Cambridge History of War: Volume 2: War and the Medieval World, Cambridge History of War, vol. 2, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 133–150, ISBN 978-0-521-87715-2, retrieved 2024-01-16

- ^ Maenchen-Helfen 1976, p. 436.

- ^ a b c Dobrovits 2003.

- ^ Whitby & Whitby 1986, p. 226, footnote 48.

- ^ CNG 2009.

- ^ Nechaeva 2011.

- ^ Tezcan 2004.

- ^ Bak, János M.; Veszprémy, László (1 July 2018). Studies on the Illuminated Chronicle. Central European University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-963-386-262-9.

- ^ Gulyamov 1957.

- ^ Muratov 2008.

- ^ Golden 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Harmatta 2001, pp. 109–118.

- ^ Pulleyblank 1999, pp. 35, 44.

- ^ Golden 1992.

- ^ Silić & Heršak 2002.

- ^ Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido Alberto; Szécsényi-Nagy, Anna; Koncz, István; Csiky, Gergely; Rácz, Zsófia; Rohrlach, A. B.; Brandt, Guido; Rohland, Nadin; Csáky, Veronika; Cheronet, Olivia; Szeifert, Bea; Rácz, Tibor Ákos; Benedek, András; Bernert, Zsolt; Berta, Norbert (2022-04-14). "Ancient genomes reveal origin and rapid trans-Eurasian migration of 7th century Avar elites". Cell. 185 (8): 1402–1413.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.007. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 9042794. PMID 35366416.

While we can conclude that the Rouran most likely called themselves Avars, to what extent the European Avars were descended from them has been debated (Dobrovits, 2003; Pohl, 2018). ... Striking genetic similarity between early Avar elites and the Rouran in Mongolia

- ^ a b Shimunek, Andrew (2017). Languages of Ancient Southern Mongolia and North China: a Historical-Comparative Study of the Serbi or Xianbei Branch of the Serbi-Mongolic Language Family, with an Analysis of Northeastern Frontier Chinese and Old Tibetan Phonology. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-10855-3. OCLC 993110372.

- ^ Jarnut & Pohl 2003, pp. 477–478.

- ^ Bálint 2010, p. 150.

- ^ Pohl 1998.

- ^ Savelyev, Alexander; Jeong, Choongwon (2020). "Early nomads of the Eastern Steppe and their tentative connections in the West". Evolutionary Human Sciences. 2: e20. doi:10.1017/ehs.2020.18. hdl:21.11116/0000-0007-772B-4. ISSN 2513-843X. PMC 7612788. PMID 35663512.

- ^ a b c Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido Alberto (14 April 2022). "Ancient genomes reveal origin and rapid trans-Eurasian migration of 7th century Avar elites". Cell. 185 (8): 1402–1413.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.007. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 9042794. PMID 35366416.

All of these individuals, albeit variably mixed with other sources, have been shown to trace their eastern Eurasian ancestry component to a genetic profile referred to as the "ancient northeast Asians" (ANA) (...) All of the early-Avar-period individuals (DTI_early_elite), except for an infant and a burial with typical characteristics of the Transtisza group (Figure 2B), form a tight cluster with a high level of ANA ancestry.

- ^ a b Gnecchi-Ruscone et al. 2022:They are located between present-day Mongolic- (e.g., Buryats and Khamnigans) and Tungusic/Nivkh-speaking populations (e.g., Negidals, Nanai, Ulchi, and Nivkhs) together with the only available ancient genome from the Rouran-period Mongolia and are close to the three AR_Xianbei_P_2c individuals in the PCA

- ^ Golden 1984, pp. 11–12, 26.

- ^ a b Fóthi 2000, pp. 87–94.

- ^ Acta Archaeologica, 1967 & 86.

- ^ Oshanin 1964, p. 21.

- ^ Lipták 1955.

- ^ Kubik 2008, p. 151.

- ^ Csősz & Szécsényi-Nagy 2016, p. 1.

- ^ Csősz & Szécsényi-Nagy 2016, pp. 2–4.

- ^ Csősz & Szécsényi-Nagy 2016, p. 1. "[T]he analyzed Avars represents a certain group of the Avar society that shows East and South European genetic characteristics..."

- ^ Šebest & Baldovič 2018, p. 1.

- ^ Šebest & Baldovič 2018, pp. 1, 6.

- ^ Šebest & Baldovič 2018, p. 14.

- ^ Šebest & Baldovič 2018, p. 14. "The most probable explanation of our findings could be that the assimilation rate of Avars and Slavs was already relatively high in theanalyzed mixed ancient population, where a majority of the inter-ethnic marriages involved Avar men and Slavic women."

- ^ a b c Neparáczki & Maróti 2019, p. 3, Figure 1.

- ^ Neparáczki & Maróti 2019, pp. 5–7. "All Hun and Avar age samples had inherently dark eye/hair colors... 8/15 Avar age individuals showed predominantly East Asian origin with both methods, 4 individuals were definitely European, while two showed evidence of admixture."

- ^ Csáky & Gerber 2020, p. 1.

- ^ Csáky & Gerber 2020, pp. 1, 4.

- ^ Csáky & Gerber 2020, pp. 1, 9–10.

- ^ Keyser & Zvénigorosky 2020:[O]ur findings confirmed that the Xiongnu had a strongly admixed mitochondrial and Y-chromosome gene pools and revealed a significant western component in the Xiongnu group studied.... [W]e propose Scytho-Siberians as ancestors of the Xiongnu and Huns as their descendants... [E]ast Eurasian R1a subclades R1a1a1b2a-Z94 and R1a1a1b2a2-Z2124 were a common element of the Hun, Avar and Hungarian Conqueror elite and very likely belonged to the branch that was observed in our Xiongnu samples. Moreover, haplogroups Q1a and N1a were also major components of these nomadic groups, reinforcing the view that Huns (and thus Avars and Hungarian invaders) might derive from the Xiongnu as was proposed until the eighteenth century but strongly disputed since... Some Xiongnu paternal and maternal haplotypes could be found in the gene pool of the Huns, the Avars, as well as Mongolian and Hungarian conquerors.

- ^ Balinova, Natalia; Post, Helen; Kushniarevich, Alena; Flores, Rodrigo; Karmin, Monika; Sahakyan, Hovhannes; Reidla, Maere; Metspalu, Ene; Litvinov, Sergey; Dzhaubermezov, Murat; Akhmetova, Vita; Khusainova, Rita; Endicott, Phillip; Khusnutdinova, Elza; Orlova, Keemya (September 2019). "Y-chromosomal analysis of clan structure of Kalmyks, the only European Mongol people, and their relationship to Oirat-Mongols of Inner Asia". European Journal of Human Genetics. 27 (9): 1466–1474. doi:10.1038/s41431-019-0399-0. ISSN 1476-5438. PMC 6777519. PMID 30976109.

- ^ a b Pohl 1998, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Curta 2001.

- ^ Evans 2005, p. xxxv: An Avar embassy first appeared in Constantinople in 558, asking for land within the empire and calling for an annual subsidy. Justinian granted them a subsidy, but for land he directed them elsewhere.

- ^ a b c d e Makkai & Mócsy 2001.

- ^ Curta 2019, p. 65.

- ^ Pohl 2002, p. 158.

- ^ Pohl 1988, p. 181.

- ^ The fate of Samo's empire after his death is unclear; it is generally assumed to have disappeared. Archaeological findings show that the Avars returned to their previous territories—at least to southernmost part of present-day Slovakia—and entered into a symbiotic relationship with the Slavs, whereas to the north of the Avar empire was purely Wend territory. The first specific knowledge of the presence of Slavs and Avars in this area is the existence in the late 8th century of the Moravian and Nitrian principalities (see Great Moravia) that were attacking the Avars and the defeat of the Avars by the Franks under Charlemagne in 799 or 802–803.

- ^ Kardaras 2019, p. 94.

- ^ All the Slavs of the Miracles of Saint Demetrius – Book II: V. Concerning the Civil War Planned Secretly Against our City by the Bulgars Mauros and Kouver

- ^ Curta 2019, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Barford 2001, p. 78.

- ^ Curta 2006, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b Barford 2001, p. 79.

- ^ Curta 2006, p. 92.

- ^ Kristó 1996, p. 93.

- ^ Havlík 2004, p. 228.

- ^ Exhibition Menoroth from čelarevo : Jewish Historical Museum in Belgrade, Museum of the City of Novi Sad = Izložba Menore iz čelareva. Authors:Exposition itinérante nationale, Radovan Bunardžić. Fedération of Jewish Communities in Yugoslavia, Belgrade, 1980.

- ^ Bowlus 1995, pp. 47, 80.

- ^ a b Pohl 2018, pp. 378–379.

- ^ a b c d Schutz 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Schutz 2004, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Duruy 1891, p. 446.

- ^ Sinor 1990, pp. 218–220.

- ^ ...(sc. Avaros) autem, qui obediebant fidei et baptismum sunt consecuti...

- ^ Schutz 2004, p. 62.

- ^ a b Skutsch 2005, p. 158.

- ^ Pohl 1998, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Olajos 2001, pp. 50–56.

- ^ "Et primo quidem Pannoniorum et Avarum solitudines pererrantes"

- ^ Ančić, Shepard & Vedriš 2017.

- ^ a b Fine 1991, p. 79.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 264.

- ^ Živković 2012, pp. 51, 117–118.

- ^ Sokol 2008, pp. 185–187.

- ^ Lukács.

- ^ Fouracre 2005.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica & Avar.

- ^ a b Waldman & Mason 2006, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Beckwith 2009, pp. 390–391.

- ^ Kyzlasov 1996, p. 322.

- ^ Dopsch 2004.

- ^ a b Szadeczky-Kardoss 1990, p. 221.

- ^ Futaky 2001.

- ^ Helimski 2000a.

- ^ Helimski 2000b, pp. 43–56.

- ^ Róna-Tas 1999, p. 116.

- ^ Curta 2004, pp. 132–148.

- ^ Gyula 1982.

- ^ Curta, Florin (2004). "The Slavic lingua franca (Linguistic notes of an archaeologist turned historian)". East Central Europe/L'Europe du Centre-Est. 31: 125–148. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ Kiley 2012.

- ^ Maurice 1984.

- ^ László 1978.

- ^ Neparáczki 2017, pp. 61–65.

- ^ Neparáczki & et al. 2017, pp. 201–214:According to Neparáczki: "From all recent and archaic populations tested the Volga Tatars show the smallest genetic distance to the entire conqueror population" and "a direct genetic relation of the Conquerors to Onogur-Bulgar ancestors of these groups is very feasible."

- ^ Neparáczki & et al. 2018, p. e0205920.

References

[edit]- L. N. Gumilev (1967). "New data on the history of the Khazars" (PDF). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 19. Magyar Tudományos Akadémia: 86. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-11-02.

- Ančić, Mladen; Shepard, Jonathan; Vedriš, Trpimir (2017). Imperial Spheres and the Adriatic: Byzantium, the Carolingians and the Treaty of Aachen (812). Routledge. ISBN 978-1351614290 – via Google Books.

- Bálint, Csanád (2010). "Some problems in genetic research on Hungarian ethnogenesis". Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 61 (1): 283–294. doi:10.1556/aarch.61.2010.1.9.

- Barford, Paul M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801439779.

- Barker, John W. (1966). Justinian and the Later Roman Empire. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299039448.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009). Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691135892. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Bowlus, Charles R. (1995). Franks, Moravians, and Magyars: The Struggle for the Middle Danube, 788–907. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812232769.

- Breuer, E. (2005). Chronological Studies to Early-Medieval Findings at the Danube Region. An Introduction to Byzantine Art at Barbaric Cemeteries. Tettnang.

- Chamberlin, Russell (2004). The Emperor Charlemagne. Sutton Publishing. pp. 181–182.

- "CNG: Feature Auction Triton XII. AVARS. Uncertain king. 6th–7th centuries AD. AV Solidus (4.33 g, 6h). Imitating Ravenna mint types of Heraclius". CNG. 2009.

- Csáky, Veronika; Gerber, Dániel (January 22, 2020). "Genetic insights into the social organisation of the Avar period elite in the 7th century AD Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. 10 (948). Nature Research: 948. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10..948C. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-57378-8. PMC 6976699. PMID 31969576.

- Csősz, Aranka; Szécsényi-Nagy, Anna (September 16, 2016). "Maternal Genetic Ancestry and Legacy of 10th Century AD Hungarians". Scientific Reports. 6 (33446). Nature Research: 33446. Bibcode:2016NatSR...633446C. doi:10.1038/srep33446. PMC 5025779. PMID 27633963.

- Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, c. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139428880.

- Curta, Florin (2004). "The Slavic lingua franca (Linguistic notes of an archaeologist turned historian)". East Central Europe. 31: 125–148. doi:10.1163/187633004X00134. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521815390.

- Curta, Florin (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500–1300) (2 Vols). Boston: Brill. p. 65. ISBN 978-90-04-39519-0. OCLC 1111434007.

- David, Ariel (2022-04-01). "Study Reveals Origin of the Mysterious Avars, Who Crushed the Roman Empire". Haaretz. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- Dobrovits, Mihály (2003). ""They called themselves Avar" – Considering the pseudo-Avar question in the work of Theophylaktos". Ērān Ud Anērān Webfestschrift Marshak.

- Dopsch, Heinz (2004). "Steppenvölker im mittelalterlichen Osteuropa: Hunnen, Awaren, Ungarn und Mongolen". Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Mittelalter und Frühneuzeit. University of Salzburg.

- Duruy, Victor (1891). Adams, George Burton (ed.). The History of the Middle Ages. Translated by Whitney, Emily Henrietta; Whitney, Margaret Dwight. H. Holt. p. 446.

- "Avars". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- Evans, James Allen Stewart (2005). The Emperor Justinian And The Byzantine Empire. Greenwood Guides to Historic Events of the Ancient World. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. xxxv. ISBN 978-0-313-32582-3. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- "Avar". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

Avar, one of a people of undetermined origin and language...

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fóthi, Erzsébet (2000). "Anthropological conclusions of the study of Roman and Migration periods". Acta Biologica Szegediensis. 44 (1–4): 87–94.

- Fouracre, Paul, ed. (2005). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521362917. ISBN 978-0521362917.

- Frassetto, Michael (2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. ABC-CLIO. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1576072639. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

The exact origins of the Avars remain uncertain...

- de la Fuente, José Andrés Alonso (2015). "Tungusic historical linguistics and the Buyla (a.k.a. Nagyszentmiklós) inscription". Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia. 20 (1).

- Futaky, I. (2001). Nyelvtörténeti vizsgálatok a Kárpát-medencei avar-magyar kapcsolatok kérdéséhez. Mongol és mandzsu-tunguz elemek nyelvünkben (in Hungarian). Budapest.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Genito, Bruno; Madaras, Laszlo, eds. (2005). Archaeological Remains of a Steppe people in the Hungarian Great Plain: The Avarian Cemetery at Öcsöd 59. Final Reports. Naples. Università degli Studi di Napoli L'Orientale. ISSN 1824-6117.

- Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido Alberto; Szécsényi-Nagy, Anna; Koncz, István; Csiky, Gergely; Rácz, Zsófia; Rohrlach, A. B.; Brandt, Guido; Rohland, Nadin; Csáky, Veronika; Cheronet, Olivia; Szeifert, Bea (2022-04-14). "Ancient genomes reveal origin and rapid trans-Eurasian migration of 7th century Avar elites". Cell. 185 (8): 1402–1413.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.03.007. ISSN 0092-8674. PMC 9042794. PMID 35366416. S2CID 247859905.

- Golden, Peter B. (1984). Halas-kun, Tibor; Martinez, A.P.; Noonan, Th. S. (eds.). Archivum Eurasiae Medii Aevi. Vol. 4. Otto Harrassowitz.

- Golden, Peter B. (1992). An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East. O. Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3447032742.

- Golden, Peter B. (2006). "Turks and Iranians: a cultural sketch". In Johanson, Lars; Bulut, Christiane (eds.). Turkic-Iranian Contact Areas: Historical and Linguistic Aspects. Turcologica Series. Vol. 62. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 19. ISBN 978-3447052764.

- Goldberg, Eric J. (2006). Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict under Louis the German, 817-876. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801438905.

- Grousset, René (1939). The Empire of the Steppes (in French). Rutgers University Press. p. 171.

- Gulyamov, Ya (1957). История орошения Хорезма с древнейших времен до наших дней [Gulyamov Ya.G. The history of irrigation of Khorezm from ancient times to the present day]. Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Uzbek SSR.

- Harmatta, Janos (2001). "The letter sent by the Turk Khagan to the Emperor Mauricius" (PDF). Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 41: 109–118. doi:10.1556/AAnt.41.2001.1-2.11. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-11-16.

- Havlík, Lubomír E. (2004). "Great Moravia between the Franconians, Byzantium and Rome". In Champion, T. C. (ed.). Centre and Periphery: Comparative Studies in Archaeology. Routledge. pp. 227–237. ISBN 0-415-12253-8.

- Helimski, Eugene (2000a). "Язык(и) аваров: тунгусо-маньчжурский аспект". Folia Orientalia 36 (Festschrift for St. Stachowski) (in Russian). pp. 135–148.

- Helimski, Eugene (2000b). "On probable Tungus-Manchurian origin of the Buyla inscription from Nagy-Szentmiklós (preliminary communication)". Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia (5): 43–56.

- Helimski, E (2004). "Die Sprache(n) der Awaren: Die mandschu-tungusische Alternative". Proceedings of the First International Conference on Manchu-Tungus Studies, Vol. II: 59–72.

- Jarnut, Jorg; Pohl, Walter (2003). Regna and Gentes: The Relationship Between Late Antique and Early Medieval Peoples and Kingdoms in the Transformation of the Roman World. Brill. ISBN 90-04-12524-8.

- Kardaras, Geōrgios (2019). Byzantium and the Avars, 6th–9th Century AD: Political, Diplomatic and Cultural Relations. Brill. p. 94. ISBN 9789004248380.

- Keyser, Christine; Zvénigorosky, Vincent (July 30, 2020). "Genetic evidence suggests a sense of family, parity and conquest in the Xiongnu Iron Age nomads of Mongolia". Human Genetics. 557 (7705). Springer: 369–373. doi:10.1007/s00439-020-02209-4. PMID 32734383. S2CID 220881540. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- Kiley, Kevin F. (2012). An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Uniforms of the Roman World. Lorenz Books.

- Kristó, Gyula (1996). Hungarian History in the Ninth Century. Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. ISBN 1-4039-6929-9.

- Kubik, Adam (2008). "The Kizil Caves as an terminus post quem of the Central and Western Asiatic pear-shape spangenhelm type helmets The David Collection helmet and its place in the evolution of multisegmented dome helmets, Historia i Świat nr 7/2018, 141–156". Histïria I Swiat. 7: 151.

- "The Kultegin Inscription (1–40 lines)". Language Committee of Ministry of Culture and Information of RK. Archived from the original on 2018-06-24. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- Kyzlasov, L. R. (1996). "Northern Nomads". In Litvinsky, B. A. (ed.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. UNESCO. pp. 315–325. ISBN 978-9231032110. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- – YouTube Documentary with Gyula László in Hungarian, on state television channel Duna.

- László, Gyula (1978). A "kettős honfoglalás. Magvető Könyvkiadó.

- Gyula, László (1982). "História 1982-01". História (in Hungarian). Digitális Tankönyvtár. Archived from the original on 2017-04-01. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- Lipták, Pál (1955). "Recherches anthropologiques sur les ossements avares des environs d'Üllö". Acta Archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae (in French). 6: 231–314.

- Lukács, B. "For the Memory of the Avar Khagans". Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- Luthar, Oto, ed. (2008). The Land Between: A History of Slovenia. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3631570111.

- Maenchen-Helfen, Otto (1976). The World of the Huns: Studies in Their History and Culture. University California Press. ISBN 978-0520015968.

- Makkai, László; Mócsy, András, eds. (2001). "II.4: The Period of Avar Rule". History of Transylvania. Vol. 1.

- Maróti, Zoltán; Neparáczki, Endre; Schütz, Oszkár (2022-05-25). "The genetic origin of Huns, Avars, and conquering Hungarians". Current Biology. 32 (13): 2858–2870.e7. Bibcode:2022CBio...32E2858M. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.04.093. PMID 35617951. S2CID 246191357.

- Nechaeva, Ekaterina (2011). "The 'Runaway' Avars and Late Antique Diplomacy". In Mathisen, Ralph W.; Shanzer, Danuta (eds.). Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity. Ashgate.

- Maurice (1984) [500s]. Maurice's Strategikon: Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy. Translated by Dennis, George T. University of Pennsylvania Press. Retrieved 2022-08-29.

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 978-0884020219.

- Muratov, B.A. (2008-06-27). Аланы, кавары и хиониты в этногенезе башкир [Alans, Kavars and Chionites in the ethnogenesis of the Bashkirs] (Report). Ural-Altai: through the centuries into the future: Proceedings of the All-Russian Scientific Conference.

- Neparáczki, Endre Dávid (2017). A honfoglalók genetikai származásának és rokonsági viszonyainak vizsgálata archeogenetikai módszerekkel [Archeogenetic analysis of the origin and genetic relations of the Hungarian conquerors] (Doctoral thesis) (in Hungarian). pp. 61–65. doi:10.14232/phd.3794.

- Neparáczki, Endre; Juhász, Zoltán; Pamjav, Horolma; Fehér, Tibor; Csányi, Bernadett; Zink, Albert; Maixner, Frank; Pálfi, György; Molnár, Erika; Pap, Ildikó; Kustár, Ágnes; Révész, László; Raskó, István; Török, Tibor (February 2017). "Genetic structure of the early Hungarian conquerors inferred from mtDNA haplotypes and Y-chromosome haplogroups in a small cemetery". Molecular Genetics and Genomics. 292 (1): 201–214. doi:10.1007/s00438-016-1267-z. PMID 27803981. S2CID 4099313.

- Neparáczki, Endre; Maróti, Zoltán; Kalmár, Tibor; Kocsy, Klaudia; Maár, Kitti; Bihari, Péter; Nagy, István; Fóthi, Erzsébet; Pap, Ildikó; Kustár, Ágnes; Pálfi, György; Raskó, István; Zink, Albert; Török, Tibor (2018-10-18). Caramelli, David (ed.). "Mitogenomic data indicate admixture components of Central-Inner Asian and Srubnaya origin in the conquering Hungarians". PLOS ONE. 13 (10). Public Library of Science (PLoS): e0205920. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1305920N. bioRxiv 10.1101/250688. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0205920. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6193700. PMID 30335830. S2CID 90886641.

- Neparáczki, Endre; Maróti, Zoltán (November 12, 2019). "Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. 9 (16569). Nature Research: 16569. Bibcode:2019NatSR...916569N. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5. PMC 6851379. PMID 31719606.

- Olajos, Teréz (2001). "Az avar továbbélés kérdésérõl". Tiszatáj: 50–56.

- Oshanin, L.V. (1964). "Penetration of the Territory of Kirghizia and Kazakhstan by the Europeoid Iranian-speaking People from Sogdiana". In Field, Henry (ed.). Anthropological Composition of the Population of Central Asia, and the Ethnogenesis of its Peoples: II. Russian Translation Series of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Vol. 2. Translated by Maurin, Vladimir M. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

- Pertz, Georg Heinrich, ed. (1845). Einhardi Annales. Hanover.

- Pohl, Walter (1988). Die Awaren: Ein Steppenvolk im Mitteleuropa, 567–822 n. Chr (in German). C.H. Bech. ISBN 978-3406333309.

- Pohl, Walter (1998). "Conceptions of Ethnicity in Early Medieval Studies". In Little, Lester K.; Rosenwein, Barbara H. (eds.). Debating the Middle Ages: Issues and Readings. Wiley. pp. 13–24. ISBN 978-1577180081.

- Pohl, Walter (2002). Die Awaren: ein Steppenvolk im Mitteleuropa, 567–822 n. Chr (in German) (2nd ed.). C.H. Bech. pp. 26–29. ISBN 978-3-406-48969-3.

- Pohl, Walter (2018). The Avars: A Steppe Empire in Central Europe, 567–822. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1501729409.

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (1999). "The Peoples of the Steppe Frontier in Early Chinese Sources". Migracijske i etničke teme. 15 (1–2).

- Richards, Ronald O. (2003). The Pannonian Slavic Dialect of the Common Slavic Proto-language: The View from Old Hungarian. Los Angeles: University of California. ISBN 978-0974265308.

- Šebest, Lukáš; Baldovič, Marian (January 18, 2018). "Detection of mitochondrial haplogroups in a small avar-slavic population from the eighth–ninth century AD". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 165 (3). American Association of Physical Anthropologists: 536–553. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23380. PMID 29345305.

- Pritsak, Omeljan (1982). The Slavs and the Avars. Spoleto.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[ISBN missing] - Róna-Tas, András (1999). Hungarians and Europe in the Early Middle Ages: An Introduction to Early Hungarian History. Central European University Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-9639116481.

- Saag, Lehti; Staniuk, Robert (11 July 2022). "Historical human migrations: From the steppe to the basin". Current Biology. 32 (13): 38–41. Bibcode:2022CBio...32.R738S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.05.058. PMID 35820383. S2CID 250443139.

Many migrations during human history have made the Carpathian Basin the melting pot of Europe. New ancient genomes confirm the Asian origin of European Huns, Avars and Magyars and huge within-group variability that is linked with social structure.

- Schutz, Herbert (2004). The Carolingians in Central Europe, Their History, Arts, and Architecture: A Cultural History of Central Europe, 750–900. Brill. pp. 61–. ISBN 90-04-13149-3.

- Silić, Ana; Heršak, Emil (2002-09-30). "The Avars: A Review of Their Ethnogenesis and History". Migracijske I Etničke Teme (in Croatian). 18 (2–3): 197–224. ISSN 1333-2546.

- Sinor, Denis (1990). "The Avars". The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 206–. ISBN 978-0-521-24304-9.

- Scholz, Bernhard Walter, ed. (1970). Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472061860.

- Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. New York: Routledge. p. 158. ISBN 1-57958-468-3.

- Sokol, Vladimir (2008). "Arheološka istraživanja u Lici' i 'Arheologija peći i krša' Gospić, 16–19. listopada 2007" [An early Croatian spur from Brušani in Lika: Some early historical aspects of the Lika region – the 'banat' problem]. Izdanja Hrvatskog arheološkog društva. 23. Zagreb-Gospić: 185–187.

- Szadeczky-Kardoss, Samuel (1990). "The Avars". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Vol. 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 221

- Tezcan, Mehmet (2004-07-24). "The Ethnonym Apar in the Turkish Inscriptions of the VIII. Century and Armenian Manuscripts" (PDF). Ērān ud Anērān Webfestschrift Marshak. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2005-03-10.

- Waldman, Carl; Mason, Catherine (2006). Encyclopedia of European Peoples. Infobase Publishing. pp. 46–49. ISBN 978-1-4381-2918-1. Retrieved 5 May 2013.

- Whitby, Michael; Whitby, Mary (1986). The History of Theophylact Simocatta: An English Translation with Introduction and Notes. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822799-1.

- Živković, Tibor (2012). De conversione Croatorum et Serborum: A Lost Source. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 51, 117–118.

External links

[edit]- Pannonian Avars

- States and territories established in the 560s

- States and territories disestablished in the 820s

- Medieval history of Bulgaria

- Medieval history of Russia

- Medieval history of Ukraine

- Hungary in the Early Middle Ages

- Romania in the Early Middle Ages

- Moldova in the Early Middle Ages

- 6th century in the Byzantine Empire

- Migration Period

- Medieval ethnic groups of Europe

- Barbarian kingdoms

- Turco-Mongol

- 6th-century establishments in Europe

- 9th-century disestablishments in Europe

- 560s establishments

- 820s disestablishments