William Coddington

William Coddington | |

|---|---|

Memorial marker for William Coddington dedicated on 200th anniversary of Newport founding | |

| 1st Judge (governor) of Portsmouth | |

| In office 1638–1639 | |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | William Hutchinson |

| Judge (governor) of Newport | |

| In office 1639–1640 | |

| Preceded by | position established |

| Succeeded by | Himself as governor of Newport and Portsmouth |

| Governor of Newport and Portsmouth | |

| In office 1640–1647 | |

| Preceded by | William Hutchinson as Judge of Portsmouth Himself as Judge of Newport |

| Succeeded by | John Coggeshall as President of Rhode Island |

| 1st Governor of Newport and Portsmouth (under Coddington Commission) | |

| In office 1651–1653 | |

| Preceded by | Nicholas Easton as President of Rhode Island |

| Succeeded by | John Sanford |

| 5th and 8th Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

| In office 1674–1676 | |

| Preceded by | Nicholas Easton |

| Succeeded by | Walter Clarke |

| In office 1678–1678 | |

| Preceded by | Benedict Arnold |

| Succeeded by | John Cranston |

| 7th Deputy Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

| In office 1673–1674 | |

| Governor | Nicholas Easton |

| Preceded by | John Cranston |

| Succeeded by | John Easton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1601 Marston, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 1 November 1678 Newport, Rhode Island |

| Resting place | Coddington Cemetery, Newport, Rhode Island |

| Spouses |

|

| Occupation | Merchant, treasurer, selectman, assistant, president, commissioner, deputy governor, governor |

| Signature | |

William Coddington (c. 1601 – 1 November 1678) was an early magistrate of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and later of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He served as the judge of Portsmouth and Newport in that colony, governor of Portsmouth and Newport, deputy governor of the four-town colony, and then governor of the entire colony. Coddington was born and raised in Lincolnshire, England. He accompanied the Winthrop Fleet on its voyage to New England in 1630, becoming an early leader in Boston. There he built the first brick house and became heavily involved in the local government as an assistant magistrate, treasurer, and deputy.

Coddington was a member of the Boston church under the Reverend John Cotton, and was caught up in the events of the Antinomian Controversy from 1636 to 1638. The Reverend John Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson were banished from the Massachusetts colony, and many of their supporters were also compelled to leave. Coddington was not asked to depart, but he felt that the outcome of the controversy was unjust and decided to join many of his fellow parishioners in exile. He was the lead signer of a compact to form a Christian-based government away from Massachusetts. He was encouraged by Roger Williams to settle on the Narragansett Bay. He and other supporters of Hutchinson bought Aquidneck Island from the Narragansetts. They settled there, establishing the town of Pocasset which was later named Portsmouth. Coddington was named the first "judge" of the colony, a Biblical term for governor. A division in the leadership of the town occurred within a year, and he left with several others to establish the town of Newport at the south end of the island.

In a short time, the towns of Portsmouth and Newport united, and Coddington was made the governor of the island towns from 1640 to 1647. During this period, Roger Williams had gone to England to obtain a patent to unite the four Narragansett towns of Providence, Warwick, Portsmouth, and Newport. This was done without the consent of the island towns and they resisted joining the mainland towns until 1647. Coddington was elected president of the united colony in 1648, but he would not accept the position, and complaints against him prompted the presidency to go to Jeremy Clarke. Coddington was very unhappy with Williams' patent; he returned to England, where he was eventually able to obtain a commission separating the island from the mainland towns, and making him governor of the island for an indefinite period. He was initially welcomed as governor, but complaints from both the mainland towns and members of the island towns prompted Roger Williams, John Clarke, and William Dyer to go to England to have Coddington's commission revoked. They were successful, and Dyer returned with the news in 1653. However, disagreements kept the four towns from re-uniting until the following year.

With the revocation of his commission, Coddington withdrew from public life, focusing on his mercantile interests, and becoming a member of the Religious Society of Friends. After nearly two decades away from politics, he was elected deputy governor in 1673, then governor the following year, serving two one-year terms. The relative calm of this period was shattered during his second year as governor of the colony when King Philip's War erupted in June 1675. It became the most catastrophic event in Rhode Island's colonial history. He was not re-elected in 1676, but he was elected to a final term as governor of the colony in 1678 following the death of Governor Benedict Arnold. He died a few months into this term, and was buried in the Coddington Cemetery on Farewell Street in Newport.

England and Massachusetts

[edit]William Coddington was born in Lincolnshire, England, most likely the son of Robert and Margaret Coddington of Marston.[1] His presumed father was a prosperous yeoman; the younger Coddington possessed a seal with the initials "R.C." when he was in Rhode Island, which were likely the initials of his father.[1] The source of his education is not known, but it is apparent that he was well educated because of his correspondence, and from his considerable command of English law.[2]

As a young man, he married by about 1626 and had two sons baptized at St. Botolph's Church in Boston, Lincolnshire. Both died in infancy and were buried at the same church.[1] His first wife was Mary, and speculation exists that she was Mary Burt, because Coddington once mentioned his "cousin Burt" in a letter.[3] King Charles circumvented Parliament in 1626 by raising funds through the Forced Loan, and Coddington was one of many Puritans who resisted this royal loan; his name was recorded on a list for doing so the following winter.[3]

Coddington was elected as a Massachusetts Bay assistant (magistrate) on 18 March 1629/30[4] while still in England, and he sailed to New England the following month with the Winthrop Fleet. His first wife died during their first winter in Massachusetts, and he returned to England aboard the Lion in 1631, remaining there for two years. During this visit to England, he married Mary Moseley in Terling, Essex, and she went to New England with him in 1633. She was admitted to the Boston church that summer.[5]

Coddington was a leading merchant in Boston, and he built the first brick house there.[6] He was elected an assistant every year from his arrival in New England until 1637.[7] He was the colony's treasurer from 1634 to 1636, and a deputy for Boston in 1637.[4] He was also a Boston selectman in 1634, and was on several committees overseeing land transactions in 1636 and 1637.[4]

Antinomian Controversy

[edit]As a member of the Boston Church, Coddington was pleased when John Cotton arrived in the colony in 1633, as he was one of the most noted Puritan ministers of the time. The two men had been friends in England, and Cotton had arranged in a 1630 letter for a hogshead of meal to be sent to Coddington, who was at Naumkeg (Salem) at the time.[8] Cotton became a minister of the Boston Church, joining minister John Wilson. In time, the Boston parishioners could sense a theological difference between Wilson and Cotton. Anne Hutchinson was a theologically astute midwife who had the ear of many of the colony's women, and she became outspoken in support of Cotton and condemned the theology of Wilson and most of the other ministers in the colony.

Differing religious opinions within the colony eventually became public debates. The resulting religious tension erupted into what has traditionally been called the Antinomian Controversy, but has more recently been labelled the Free Grace Controversy. Many members of Boston's church disagreed with Wilson's emphasis on morality and his doctrine of "evidencing justification by sanctification", meaning that one demonstrates salvation by living a more holy life. Some of Wilson's opponents labeled his views as a covenant of works, while Hutchinson told her followers that Wilson lacked "the seal of the Spirit".[9] Wilson's theological views were in accord with those of the other ministers in the colony except for Cotton, who stressed "the inevitability of God's will" (which he termed a covenant of grace) as opposed to preparation (works).[10] All but about five of the Boston parishioners supported Hutchinson's views,[11] and they had become accustomed to Cotton's doctrines. Some of them began disrupting Wilson's sermons, even finding excuses to leave when he got up to preach or pray.[12]

In May 1636, the Bostonians received a new ally when the Reverend John Wheelwright arrived from England and immediately aligned himself with Cotton, Hutchinson, and other so-called free grace advocates. Yet another boost came for those advocating the free grace theology during the same month when young aristocrat Henry Vane was elected governor of the colony. Vane was a strong supporter of Hutchinson, but he also had his own ideas about theology that were considered not only unorthodox, but even radical.[13]

Fast Day Sermon

[edit]Coddington was a magistrate as the events of the controversy unfolded, elected by the freemen of the colony. Like many members of the Boston church, he sided squarely with the free grace advocates. By late 1636, the theological schism had become great enough that the General Court called for a day of fasting to help ease the colony's difficulties. During the appointed fast-day on Thursday, 19 January 1637, Wheelwright preached at the Boston church in the afternoon. To the Puritan clergy, his sermon was "censurable and incited mischief".[14] The colony's ministers were offended by the sermon, while the free grace advocates were encouraged, and they became more vociferous in their opposition to the "legal" ministers. Governor Vane began challenging the doctrines of the colony's divines, and supporters of Hutchinson refused to serve during the Pequot War of 1637 because Wilson was the chaplain of the expedition.[12][15] Ministers worried that the bold stand of Hutchinson and her supporters began to threaten the "Puritan's holy experiment".[12]

As early as March 1637, the political tide began to turn against the free grace advocates. Wheelwright was tried for contempt and sedition that month for his fast-day sermon, and he was convicted in a close vote but not yet sentenced. During the election of May 1637, Henry Vane was replaced as governor by John Winthrop. In addition, Coddington and all the other Boston magistrates who supported Hutchinson and Wheelwright were voted out of office by the colony's freemen, though Coddington was then immediately elected by the town of Boston as a deputy. By the summer of 1637, Vane sailed back to England, never to return. With his departure, the time was ripe for the orthodox party to deal with the remainder of their free grace rivals.[16]

The aggressive challenges of the free grace advocates left the colony in a state of dissension. Winthrop realized that "two so opposite parties could not contain in the same body, without apparent hazard of ruin to the whole"; he opted for a stern approach to the difficulties, supported by a majority of the colonists.[17] The elections of October 1637 brought about even more change, with a large turnover of the Deputies to the General Court.[18] In contrast to the remainder of the colony, Boston continued to be represented with strong free grace advocates, and Coddington continued as one of its three deputies.[19]

The trial

[edit]The autumn court in 1637 convened on 2 November, and Wheelwright was sentenced to banishment and ordered to leave the colony within fourteen days. Several of Hutchinson and Wheelwright's other supporters were tried and given varied sentences. Following these preliminaries, it was Anne Hutchinson's turn to be tried.[20] She was brought to trial on 7 November 1637, presided over by Governor Winthrop, on the charge of "traducing [slandering] the ministers", among other charges. One of the Boston deputies had been dismissed, so the town was only represented at the trial by Coddington and one other deputy. The trial lasted for two days, and Coddington likely coached Hutchinson on legal matters at the end of the first day. The first day went well for her, but she made the work much easier for her accusers during the second day. She addressed the court with her own judgment, claiming divine revelations as her source of inspiration, and she threatened the court with a curse, as well.[21]

The stunned reaction of the court turned into an immediate call for Hutchinson's conviction. Cotton attempted to come to her defense but was hounded by the magistrates until Winthrop called off the questioning.[22] A vote was taken on a sentence of banishment; only Coddington and the other remaining deputy from Boston dissented. Winthrop then read the order: "Mrs. Hutchinson, the sentence of the court you hear is that you are banished from out of our jurisdiction as being a woman not fit for our society, and are to be imprisoned till the court shall send you away".[23]

Aftermath

[edit]Coddington was very unhappy with the proceedings. He stood and asserted:

I do not see any clear witness against her, and you know it is a rule of the court that no man may be a judge and an accuser too. I would entreat you to consider whether those things which you have alleged against her deserve such censure as you are about to pass, be it to banishment or imprisonment. I beseech you: do not speak so as to force things along, for I do not, for my own part, see any equity in the court in all your proceedings. Here is no law of God that she hath broken nor any law of the country that she hath broke, and therefore deserve no censure.[24]

Coddington's words were ignored, and the court wanted a sentence, but they could not proceed until some of the ministers spoke. Three of the ministers were sworn in, and each testified against Hutchinson. Winthrop moved to have her banished; in the ensuing tally, only Coddington and the other Boston deputy voted against conviction.[25] Hutchinson challenged the sentence's legitimacy, saying, "I desire to know wherefore I am banished". Winthrop responded with finality: "The court knows wherefore and is satisfied".[26]

Within a week of Hutchinson's sentencing, additional supporters of hers were called into court and were disenfranchised. The constables were then sent from door to door throughout the colony's towns to disarm those who signed a petition in support of Wheelwright.[27] Within ten days, these individuals were ordered to deliver "all such guns, pistols, swords, powder, shot, & match as they shall be owners of, or have in their custody, upon paine of ten pound[s] for every default".[27] A great number of those who signed the petition recanted under the pressure and "acknowledged their error" in signing the petition when faced with losing their protection and, in some cases, their livelihood. Those who refused to recant suffered hardships and, in many cases, decided to leave the colony.[28]

Rhode Island

[edit]Coddington was angry about the recent trials, considering them to be unjust, so he began making plans for his own future in consultation with others affected by the Court's decisions. He remained on good terms with Winthrop, and consulted with him about the possibility of leaving the Massachusetts colony in peace.[29] Winthrop was encouraging and helped smooth the way with the other magistrates. The men were uncertain where to go, so they contacted Roger Williams; he suggested that they purchase land along the Narragansett Bay from the Narragansett Indians, near his settlement in Providence.

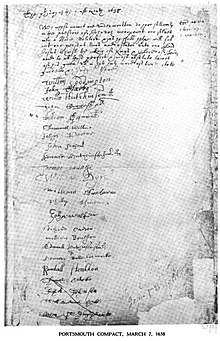

On 7 March 1638, a group of men gathered at Coddington's home and drafted a compact. [30] This group included several of the strongest supporters of Hutchinson and Wheelwright who had been disfranchised, disarmed, excommunicated, or banished, including John Coggeshall, William Dyer, William Aspinwall, John Porter, Philip Sherman, Henry Bull, and several members of the Hutchinson family. Some who were not directly involved in the events also asked to be included, such as Randall Holden and physician and theologian John Clarke.[30]

Altogether, a group of 23 individuals signed the instrument, sometimes called the Portsmouth Compact, which was intended to form a "Bodie Politick" based on Christian principles.[31] Coddington's name appears first on the list of signers, and the signers elected him as their "Judge," using this Biblical name for their ruler or governor.[31] Following through with Roger William's proposed land purchase, these exiles established their colony on Aquidneck Island (which they called Rhode Island). They initially named the settlement Pocasset but soon renamed it Portsmouth.[31]

The split

[edit]Within a year of founding this settlement, there was dissension among the leaders. Coddington, three elders, and other inhabitants moved to the south end of the island and established the town of Newport.[32] In 1640, the two towns of Portsmouth and Newport united, the name of the chief officer was changed to governor, and Coddington was elected to the position.[32]

The two island towns grew and prospered at a much greater rate than the mainland settlements of Providence Plantations and the newly established Shawomet (later Warwick). Roger Williams envisioned a union of all four settlements on the Narragansett Bay, so he went to England to obtain a patent bringing all four under one government, and he was successful in obtaining it on 14 March 1644.[a] The corporate charter obtained by the Williams group was brought from England and read to representatives of the four towns later in 1644.

Coddington was opposed to the Williams patent. As the chief magistrate of the island, he had a well-organized and thoroughly equipped government which had little in common, in his opinion, with the unorganized, discordant elements of Providence.[33] Because of this, the island towns ignored the 1643/44 patent, and the General Assembly of the two towns officially named the island on 13 April 1644 Rhode Island.[34] Coddington was so unhappy over uniting with the mainland towns that he wrote a letter to Governor John Winthrop in Massachusetts in August 1644, letting it be known that he would rather have an alliance with Massachusetts or Plymouth than with Providence.[33] This did not happen, but Coddington did manage to resist union with Providence until 1647, when representatives of the four towns finally met and adopted the Williams Patent of 1643.[35] This is also the year that Coddington's second wife Mary died in Newport.[36]

The General Court (later the General Assembly) met in Providence in May 1648, and Coddington was elected president of the entire colony. He did not attend the meeting, however, probably because he did not support the patent.[37] Charges were subsequently brought against him, though the nature of them was not recorded, and he was replaced as governor by Jeremy Clarke.[37] The 1643 patent created little more than a confederation of independent governments.[38] In September 1648, Coddington made application for admission of the two island towns into the New England Confederation.[38] The ensuing reply let him know that the island would have to submit to the Plymouth government to be considered.[38] This was unacceptable to Coddington who wanted colonial independence for the two island towns.[38] They had a well-organized government in which civil and religious liberty had been clearly defined and fully recognized, as did Providence, and these liberties would be lost in a government under Plymouth.[38]

Coddington commission

[edit]Exasperated by the situation, Coddington decided to go to England and present his case to the Colonial Commissioners in London, leaving his farm and business interests in the hands of an agent.[38] He arrived in England to find the country in the midst of a civil war, and he was delayed in getting the attention of the proper authorities.[39] He eventually met with his old friend and associate from Boston Sir Harry Vane. Vane had helped Roger Williams obtain his patent, and he was now called upon to advise Coddington as to a course of action.[39] Governor Josiah Winslow of the Plymouth Colony was also in London at the same time, urging Plymouth's claims to the two island towns.[39]

On 6 March 1650, Coddington presented his petition for an independent colonial government on Rhode Island, free from the claims of Plymouth and free from union with Providence.[39] In April 1651, the Council of State of England gave Coddington the commission of a separate government for Rhode Island (i.e., Portsmouth and Newport) and for the smaller neighboring island of Conanicut (later Jamestown), with him as governor.[39] Vane gave his consent to this, thus annulling the patent given to Roger Williams several years earlier.[39] He thought that Coddington would be a wise and effective chief magistrate and permitted him to serve as governor for an indefinite period, subject to the will of Parliament.[40] To complete the government, Coddington was to have a council of six men, elected by popular vote of the freemen.[41]

Coddington spent nearly three years in England, and he met and married Anne Brinley while there. She was the daughter of Thomas Brinley, auditor to Kings Charles I and Charles II, and sister of Francis Brinley, who settled in Newport in 1652 and built a large structure that later became the White Horse Tavern on land he obtained from the Coddingtons.[40] In August 1651, Coddington returned to the island.[41] Henry Bull of Newport said that he was welcomed upon his return from England, and that the majority of people accepted him as governor.[41] With his new commission, Coddington once again unsuccessfully sought a place for Rhode Island in the New England Confederation, consisting of the colonies of Massachusetts, Plymouth, Connecticut, and New Haven.[39]

Most writers and historians consider Coddington's efforts to be treasonous, particularly those writers who are sympathetic to the Providence and Warwick settlers, including Samuel G. Arnold.[39] Historian Thomas Bicknell, on the other hand, takes a minority position by suggesting that Coddington's actions were totally justified, and he accuses Roger Williams of usurping Coddington's successful island government with the Patent of 1643.[42] Bicknell asserts that Coddington had been the chief magistrate of a flourishing island of nearly 1,000 inhabitants, while the combined population of Providence and Warwick was about 200. In Bicknell's view, Roger Williams went to London in 1643, without advice or instructions, and returned in September 1644 with a patent for the colony, without the knowledge or consent of the island population.[42]

Regardless, the island government resisted the patent for several years until 1647, when they yielded to the patent and merged with the mainland government.[40]

Revocation of commission

[edit]Criticism soon arose concerning Coddington. The venerable Dr. John Clarke voiced his opposition to the island governor, and he and William Dyer were sent to England as agents of the discontents to get the Coddington commission revoked.[43] Simultaneously, the mainland towns of Providence and Warwick sent Roger Williams on a similar errand, and the three men sailed for England in November 1651.[43] The men did not meet with the Council of State on New England until April 1652, however, because of recent hostilities between the English and the Dutch.[43] Coddington was accused of taking sides with the Dutch on matters of colonial trade, and his commission was revoked for the island government in October 1652.[43] Dyer was the messenger who returned to Rhode Island the following February, bringing the news that the colony would return to the Williams Patent of 1643/44. The reunion of the colony was to take place that spring, but the mainland commissioners refused to come to the island to meet, and the separation of mainland from island was extended for another year.[43] During this interim period, John Sanford was elected as governor of the island towns, while Gregory Dexter became president of the mainland towns.[43] The powerless Coddington withdrew from public life to tend to his business affairs.[44]

The four towns eventually united in 1654, with Nicholas Easton of Newport chosen as president.[44] A general court of elections was then held in September 1654, and Roger Williams was elected president of the united colony, a position which he held for nearly three years.[44] In time, Coddington briefly re-entered public life and became a Newport commissioner on the General Court of Trials.[44] A committee was appointed to investigate his right to a seat, and they sent a letter to the Council of State in England asking for a full accounting of all complaints entered against him.[44] The reply fully vindicated Coddington, and an investigation in Newport cleared him of all charges brought against him.[44] He was finally able to accept the united government of the four towns, and he made the following oath in March 1656: "I William Coddington doe hereby submit to ye authoritie of His Highness in this Colonie as it is now united, and that with all my heart".[45]

Later career

[edit]

Sometime in the early 1660s, Coddington joined Governor Nicholas Easton and many other prominent citizens in becoming members of the Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as Quakers.[46][47] In March 1665, he sent a paper to the Newport commissioners concerning Quaker matters.[46]

Coddington remained out of public office for most of the two decades following the demise of his commission to govern Aquidneck Island, but he was still considered one of the colony's leading citizens, and his name appears in the Royal Charter of 1663. He eventually returned to serving the colony in May 1673, when he was elected deputy governor under Governor Nicholas Easton. At the general election a year later, he was chosen as governor, with Easton's son John elected as deputy governor.[48] Little of note occurred during this administration, other than the establishment of peace between England and the Dutch Republic, removing a large source of tension in the colonies.[49] Also, the township of Kingston was established in the Narragansett country, which became incorporated as the seventh town of the colony.[49] In May 1675, the same officers were elected in the colony and given the task of bringing the colony's weights and measures into conformity with English standards.[50]

A calm greeted this administration, but the storms of war had been brewing for years, even decades. In June 1675, the peace was shattered by an Indian massacre at Swansea[50] which began King Philip's War, the most devastating event to visit the colony of Rhode Island prior to the American Revolution. The mainland settlements of Warwick and Pawtuxet were totally destroyed during the war, and much of Providence was ruined, as well. The island towns of Newport and Portsmouth were spared with the protection of a fleet of armed vessels.[51]

During the 1676 election, Walter Clarke was elected governor, and his administration saw the end of the war. Benedict Arnold was elected governor in 1677; he died a year later, and Coddington was elected to his final term as governor. He was in office only a few months, dying at the beginning of November in 1678.

Death, family, and legacy

[edit]

Coddington died in office on 1 November 1678 and is buried in the Coddington Cemetery (Rhode Island Historic Cemetery, Newport No. 9) on Farewell Street in Newport, where several other colonial governors are also buried.[52] His grave is marked with the original marker, as well as a taller monument erected on the 200th anniversary of the establishment of Newport.[53] His oldest son William Coddington, Jr., born of his third wife, Ann Brinley Coddington, was the governor of the colony for two terms from 1683 to 1685.[36] His son Nathaniel married Susanna Hutchinson, a daughter of Edward Hutchinson, and a granddaughter of William and Anne Hutchinson.[54] His daughter Mary married Peleg Sanford, a colonial governor from 1680 to 1683, the son of earlier governor John Sanford [54] with his second wife Bridget Hutchinson, and a grandson of William and Anne Hutchinson. His grandson William Coddington III, the son of Nathaniel, married Content Arnold, the daughter of Benedict and Mary (née Turner) Arnold, and granddaughter of Governor Benedict Arnold.[55] A portrait often ascribed to Governor Coddington actually portrays this grandson, who was very active in colonial affairs but never a governor.[56]

Coddington was usually at odds with Roger Williams, who described him in a letter several years after the founding of Portsmouth (1638): "a worldly man, a selfish man, nothing for public, but all for himself and private."[57] Rhode Island historian and Lieutenant Governor Samuel G. Arnold was highly critical of Coddington for obtaining a commission to govern Aquidneck Island separately from Providence and Warwick, yet he had this to say of him: "He was a man of vigorous intellect, of strong passions, earnest in whatever he understood, and self-reliant in all his actions."[6] Historian Thomas Bicknell writes: "he rose to the achievement of a great personal and political victory, when foes became friends, his policy of statecraft vindicated, and Rhode Island Colony on Aquidneck assumed the position for which he had so stoutly contended and so shamefully suffered."[44] Coddington Hall, an upperclassmen residence hall at the University of Rhode Island is named in his honor. A harbor, street, cemetery, and apartment complex in Newport bear his name, and the Coddington Brewery restaurant in Middletown, Rhode Island is named for him.

See also

[edit]- List of colonial governors of Rhode Island

- List of lieutenant governors of Rhode Island

- List of early settlers of Rhode Island

- Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

Notes

[edit]- ^ The document bears the date 14 March 1643 because, at that time, England and English colonies utilized the Julian calendar, and March 14 was 1644 on the Gregorian calendar, being prior to Easter, but 1643 on the Julian calendar. Of special note is the fact that this document is dated 14 March 1643, but it refers to an earlier document dated 2 November 1643 in its body. This paradox is explained by the fact that the Old Style Julian Calendar begins the calendar year with Easter rather than January 1.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Moriarity 1944, p. 185.

- ^ Anderson 1995, p. 395.

- ^ a b Anderson 1995, p. 398.

- ^ a b c Anderson 1995, p. 396.

- ^ Anderson 1995, p. 397.

- ^ a b Arnold 1859, p. 448.

- ^ Bicknell 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Bush 2001, p. 40.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 105.

- ^ Bremer 1995, p. 66.

- ^ Bicknell 2005, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Bremer 1981, p. 5.

- ^ Winship 2002, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Bell 1876, p. 11.

- ^ Winship 2002, p. 116.

- ^ Winship 2002, pp. 126–148.

- ^ Hall 1990, p. 9.

- ^ Battis 1962, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 175.

- ^ Winship 2002, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 204.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 206.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 208.

- ^ Morris 1981, p. 63.

- ^ Winship 2002, pp. 182–183.

- ^ Winship 2002, p. 183.

- ^ a b Battis 1962, p. 211.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 212.

- ^ Battis 1962, p. 230.

- ^ a b Battis 1962, p. 231.

- ^ a b c Bicknell 1920, p. 975.

- ^ a b Bicknell 1920, p. 976.

- ^ a b Bicknell 1920, p. 979.

- ^ Bicknell 1920, p. 978.

- ^ Bicknell 1920, p. 980.

- ^ a b Austin 1887, p. 276.

- ^ a b Bicknell 1920, p. 981.

- ^ a b c d e f Bicknell 1920, p. 982.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bicknell 1920, p. 983.

- ^ a b c Bicknell 1920, p. 985.

- ^ a b c Bicknell 1920, p. 986.

- ^ a b Bicknell 1920, p. 984.

- ^ a b c d e f Bicknell 1920, p. 987.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bicknell 1920, p. 988.

- ^ Bicknell 1920, pp. 988–989.

- ^ a b Arnold 1859, p. 320.

- ^ Rust 2004, p. 107.

- ^ Arnold 1859, pp. 367–368.

- ^ a b Arnold 1859, p. 368.

- ^ a b Arnold 1859, p. 369.

- ^ Bicknell 1920, p. 1029.

- ^ Find-a-grave 2005.

- ^ Turner 1878, pp. 2–22.

- ^ a b Austin 1887, p. 278.

- ^ Austin 1887, p. 279.

- ^ Austin 1887, pp. 278–280.

- ^ Gorton 1907, p. 33.

Bibliography

[edit]- Anderson, Robert Charles (1995). The Great Migration Begins, Immigrants to New England 1620–1633. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-044-6.

- Arnold, Samuel Greene (1859). History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol. 1. New York: D. Appleton & Company.

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.

- Battis, Emery (1962). Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bell, Charles H. (1876). John Wheelwright. Boston: printed for the Prince Society.

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams (1920). The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol. 3. New York: The American Historical Society. pp. 975–989.

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams (2005). The Story of Dr. John Clarke (PDF). Little Rock, Arkansas: The Baptist Standard Bearer, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 November 2014.

- Bremer, Francis J. (1981). Anne Hutchinson: Troubler of the Puritan Zion. Huntington, New York: Robert E. Krieger. pp. 1–8.

- Bremer, Francis J. (1995). The Puritan Experiment, New England Society from Bradford to Edwards. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. ISBN 978-0-87451-728-6.

- Bush, Sargent, ed. (2001). The Correspondence of John Cotton. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2635-9.

- Gorton, Adelos (1907). The Life and Times of Samuel Gorton. George S. Ferguson.

- Hall, David D. (1990). The Antinomian Controversy, 1636–1638, A Documentary History. Durham [NC] and London: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1091-4.

- Moriarity, G. Andrews (April 1944). "Additions and Corrections to Austin's Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island". The American Genealogist. 20: 185.

- Morris, Richard B (1981). "Jezebel Before the Judges". In Bremer, Francis J (ed.). Anne Hutchinson: Troubler of the Puritan Zion. Huntington, New York: Robert E. Krieger. pp. 58–64.

- Rust, Val D. (2004). Radical Origins, Early Mormon Converts and Their Colonial Ancestors. University of Illinois Board of Trustees. ISBN 978-0-252-02910-3.

- Turner, H. E. (1878). William Coddington in Rhode Island Colonial Affairs: An Historical Inquiry.

- Winship, Michael Paul (2002). Making Heretics: Militant Protestantism and Free Grace in Massachusetts, 1636–1641. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08943-4.

"Online sources"

- "William Coddington". Find-a-grave. 2 November 2005. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

External links

[edit]- Chronological list of Rhode Island leaders Archived 2 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Background on Coddington portrait (Brown University online portrait collection) Provides good background on history of the portrait, but mistakenly calls William Coddington III the son of William Coddington, Jr., when he was actually the son of Nathaniel Coddington, and grandson of Gov. Coddington.

- Coddington portrait Published paper refuting the portrait being of the governor

- Forced loan Published paper about Coddington's role in refusing the forced loan, 1627