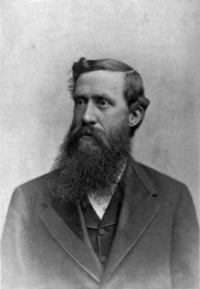

Elliott Coues

Elliott Coues | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Elliott Ladd Coues September 9, 1842 |

| Died | December 25, 1899 (aged 57) Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Columbian University |

| Known for | Key to North American Birds, taxonomic classification of subspecies |

| Spouses |

|

| Parents |

|

| Awards | Member of the American Philosophical Society |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Ornithology |

| Author abbrev. (zoology) | Coues |

Elliott Ladd Coues (/ˈkaʊz/; September 9, 1842 – December 25, 1899) was an American army surgeon, historian, ornithologist, and author.[1] He led surveys of the Arizona Territory, and later as secretary of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories. He founded the American Ornithological Union in 1883, and was editor of its publication, The Auk.

Biography

[edit]Coues was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to Samuel Elliott Coues and Charlotte Haven Ladd Coues.[2] He graduated at Columbian University, Washington, D.C., in 1861, and at the medical school of that institution in 1863. He served as a medical cadet in Washington in 1862–1863, and in 1864 was appointed assistant-surgeon in the regular army,[3] and assigned to Fort Whipple, Arizona. While there was not yet any legal provision for divorce under its laws, the 1st Arizona State Legislature granted Coues an annulment of his marriage to Sarah A. Richardson.[4][5] His marriage to Jeannie Augusta McKenney ended in divorce in 1886,[6] and he married the widow, Mary Emily Bates in October 1887.[7]

In 1872, he published his Key to North American Birds, which, revised and rewritten in 1884 and 1901, did much to promote the systematic study of ornithology in America. In 1883, he was one of three members of the Nuttall Ornithological Club that put out a call to form a "Union of American Ornithologists".[3] This would become the American Ornithologists' Union, with Coues as a founding member. He edited its journal, The Auk, and several other ornithological periodicals.[8] His work was instrumental in establishing the currently accepted standards of trinomial nomenclature – the taxonomic classification of subspecies – in ornithology, and ultimately the whole of zoology. During 1873–1876 Coues was attached as surgeon and naturalist to the United States Northern Boundary Commission, and from 1876 to 1880 he was secretary and naturalist to the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories, the publications of which he edited. He was lecturer on anatomy in the medical school of the Columbian University from 1877 to 1882, and professor of anatomy there from 1882 to 1887.[3]

He was a careful bibliographer and in his work on the Birds of the Colorado Valley, he included a special section on swallows and attempted to resolve whether they migrated in winter or hibernated under lakes as was believed at the time:

I have never seen anything of the sort, nor have I ever known one who had seen it; consequently, I know nothing of the case but what I have read about it. But I have no means of refuting the evidence, and consequently cannot refuse to recognize its validity. Nor have I aught to urge against it, beyond the degree of incredibility that attaches to highly exceptional and improbable allegations in general, and in particular the difficulty of understanding the alleged abruptness of the transition from activity to torpor. I cannot consider the evidence as inadmissible, and must admit that the alleged facts are as well attested, according to ordinary rules of evidence, as any in ornithology. It is useless as well as unscientific to pooh-pooh the notion. The asserted facts are nearly identical with the known cases of many reptiles and batrachians. They are strikingly like the known cases of many bats. They accord in general with the recognized conditions of hibernation in many mammals.

— Birds of the Colorado Valley (1878), Chapter XIV.[9]

He was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1878.[10] He resigned from the army in 1881 to devote himself entirely to scientific research. In 1899 he died in Baltimore, Maryland.[3]

Grace's warbler, a species of bird, was discovered by Elliott Coues in the Rocky Mountains in 1864. He requested that the new species be named after his 18-year-old sister, Grace Darling Coues, and his request was honored when Spencer Fullerton Baird described the species scientifically in 1865.

In addition to ornithology he did valuable work in mammalogy; his book Fur-Bearing Animals (1877) being distinguished by the accuracy and completeness of its description of species, several of which were already becoming rare.[3] Odocoileus virginianus couesi, the Coues' white-tailed deer is named after him. Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus couesi, a subspecies of the Cactus wren, is named after him and is specifically the state bird of Arizona, recognizing Coues' contributions to natural surveys of early Arizona.[11][12][13]

Spirituality

[edit]Coues took an interest in spiritualism and began speculations in Theosophy. He was a friend of Alfred Russel Wallace and they had attended séances with the medium Pierre L. O. A. Keeler.[14]

He felt the inadequacy of formal orthodox science in dealing with the deeper problems of human life and destiny. Convinced by the principles of evolution, he believed that these principles may be capable of being applied in psychical research and he proposed to use it to explain obscure phenomena such as hypnotism, clairvoyance and telepathy.[15] He claimed to have witnessed levitation of objects and developed a theory to explain the phenomenon,[16] publishing an article about his telekinetic theory of levitation in the first issue of The Metaphysical Magazine (1895).[17]

Coues joined the Theosophical Society in July, 1884.[18] He visited Helena Blavatsky in Europe. He founded the Gnostic Theosophical Society of Washington, and in 1890 became the president of the Theosophical Society. He later became highly critical of Blavatsky and lost interest in the Theosophical movement.[15]

Coues wrote an attack on Blavatsky entitled "Blavatsky Unveiled!" in The Sun newspaper on July 20, 1890. The article prompted Blavatsky to file a legal suit against Coues and the newspaper but it was terminated as she died in 1891.[19] He fell out with Theosophical leaders such as William Quan Judge and was expelled from the Theosophical Society in June 1899 for "untheosophical conduct".[18][19] Coues retained interest in oriental religious thought and later studied Islam.[18]

Publications

[edit]Among his publications are:

- A Field Ornithology (1874)

- Birds of the North-west (1874)

- Monographs on North American Rodentia, with Joel Asaph Allen (1877)

- Birds of the Colorado Valley (1878)

- A Bibliography of Ornithology (1878–1880, incomplete)

- New England Bird Life (1881)

- A Dictionary and Check List of North American Birds (1882)

- Biogen: A Speculation on the Origin and Nature of Life (1884)

- The Daemon of Darwin (1884)

- Can Matter Think? (1886)

- Neuro-Myology (1887)[3]

- Blavatsky Unveiled! (1890)

- Rural Bird Life of England, with Charles Dixon (1895)

Coues also contributed numerous articles to the Century Dictionary, wrote for various encyclopaedias, and edited:

- Journals of Lewis and Clark (1893);

- The Travels of Zebulon M. Pike (1895);

- New Light on the Early History of the Greater Northwest: The Manuscript Journals of Alexander Henry, Fur Trader of the Northwest Company and of David Thompson, Official Geographer and Explorer of the Same Company, 1799–1814 (1897);

- Forty Years A Fur Trader on the Upper Missouri: The Personal Narrative of Charles Larpenteur 1833–1872 (1898).

- On the Trail of a Spanish Pioneer: the Diary and Itinerary of Francisco Garces (Missionary Priest), New York, Francis P. Harper, 1900

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Smith, Alfred Emanuel (January 13, 1900). "A Great Ornithologist". The Outlook. 64: 98. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- ^ Victor, Frances F. (1 June 1900). "Dr. Elliott Coues". The Quarterly of the Oregon Historical Society. 1 (1577): 192. Bibcode:1900Natur..61R.278N. doi:10.1038/061278b0. S2CID 4006732.

- ^ a b c d e f One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Coues, Elliott". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 308.

- ^ "Acts". Acts, Resolutions and Memorials, Adopted by the First Legislative Assembly of the Territory of Arizona.

- ^ Tackenberg, Dave (August 20, 2008). "MS 178; Coues, Elliott; Papers, 1864" (PDF). ARIZONA HISTORICAL SOCIETY. Retrieved August 19, 2019.

- ^ Cutright, Paul Russell (1 April 2000). A History of the Lewis and Clark Journals. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3247-1. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "From the Archives" (PDF). Theosophical History. 5 (3): 16. July 1994. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ "The American Ornithologists' Union". Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club. VIII (4): 221–226. October 1883.

- ^ Allen, J.A. (1909). "Biographical memoir of Elliott Coues" (PDF). National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoirs. 6: 395–446.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 2021-05-10.

- ^ Tackenberg, Dave (20 August 2008). "MS 178; Coues, Elliott; Papers, 1864" (PDF). Arizona Historical Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. S2CID 82496461.

- ^ Anderson, Anders H.; Anderson, Anne (1972). The Cactus Wren. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 1. ISBN 0816503990. OCLC 578051.

- ^ Slotten, Ross A. (2004). The Heretic in Darwin's Court: The Life of Alfred Russel Wallace. Columbia University Press. pp. 388-389. ISBN 978-0-231-13011-0

- ^ a b Marble, C. C. (1900). The Late Dr. Elliott Coues. Birds and All Nature: February, 1900.

- ^ Cutright, Paul Russell; Brodhead, Michael J. (2001). Elliott Coues: Naturalist and Frontier Historian. University of Illinois Press. p. 302. ISBN 978-0252069871

- ^ Coues, Elliott. "The Telekinetic Theory of Levitation". The Metaphysical Magazine, vol. 1, January 1895, pp. 1–11.

- ^ a b c Bowen, Patrick D. (2015). A History of Conversion to Islam in the United States, Volume 1: White American Muslims Before 1975. Brill. p. 149. ISBN 978-90-04-29994-8

- ^ a b Dimolianis, Spiro. (2011). Jack the Ripper and Black Magic: Victorian Conspiracy Theories, Secret Societies and the Supernatural Mystique of the Whitechapel Murders. McFarland. pp. 106-107. ISBN 978-0-7864-4547-9

External links

[edit]- 19th-century American zoologists

- 1842 births

- 1899 deaths

- American ornithologists

- American taxonomists

- American Theosophists

- Columbia University faculty

- Burials at Arlington National Cemetery

- Columbian College of Arts and Sciences alumni

- Critics of Theosophy

- Gonzaga College High School alumni

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- American parapsychologists

- Union army officers

- Writers from Portsmouth, New Hampshire