Pitmatic

| Pitmatic | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /pIt'mretIk/ |

| Region | Great Northern Coalfield |

Early form | |

| English alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | nort3300 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABA-aba |

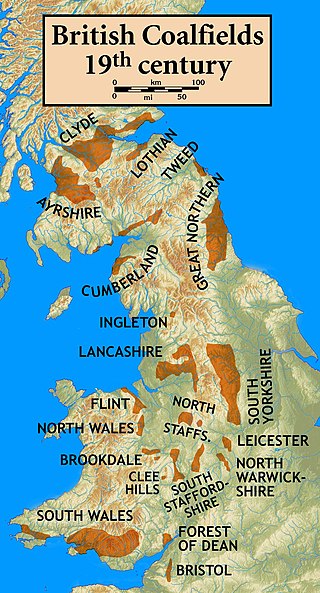

Map of 19th-century coalfields in Great Britain showing, near top-right, the Great Northern Coalfield, the home of Pitmatic.[1] | |

Pitmatic – originally 'pitmatical'[2] – is a group of traditional Northern English dialects spoken in rural areas of the Great Northern Coalfield in England.

The feature distinguishing Pitmatic from other Northumbrian dialects, such as Geordie and Mackem, is its basis in the mining jargon used in local collieries. For example, in Tyneside and Northumberland, Cuddy is a nickname for St. Cuthbert, while in Alnwick Pitmatic, a cuddy is a pit pony.[3] According to the British Library's lead curator of spoken English, writing in 2019, "Locals insist there are significant differences between Geordie and several other local dialects, such as Pitmatic and Mackem. Pitmatic is the dialect of the former mining areas in County Durham and around Ashington to the north of Newcastle upon Tyne, while Mackem is used locally to refer to the dialect of the city of Sunderland and the surrounding urban area of Wearside".[4]

Traditionally, the dialect used the Northumbrian burr wherein /r/ is realised as [ʁ]. [5]This is now less frequently heard; since the closure of the area's deep mines, younger people speak in local ways that do not usually include this characteristic. The guttural r sound can, however, still sometimes be detected amongst elderly populations in rural areas.

Dialectology

[edit]While Pitmatic was spoken by miners throughout the Great Northern Coalfield — from Ashington in Northumberland to Fishburn in County Durham — sources describe its particular use in the Durham collieries.[2][6][7][8] However, Pitmatic is not a homogenous dialect, and varies between and within the two counties. The Durham coalfield is grouped linguistically with Wearside under the 'Central Urban North-Eastern English' dialect region, while the Northumberland coalfield is grouped with Tyneside as part of the 'Northern Urban North-Eastern English' area.[9]: 20–23

Dictionaries and compilations

[edit]Although he did not use the term "Pitmatic", Alexander J. Ellis's seminal survey of English dialects in the late nineteenth century included the language of "Pitmen",[10]: 637–641 focusing on the region "between rivers Tyne and Wansbeck" and drawing on informants from Humshaugh, Earsdon, and Backworth.[10]: 674 Dialect words in Northumberland and Tyneside, including many specific to the coal-mining industry, were collected by Oliver Heslop and published in two volumes in 1892 and 1894 respectively.[11]

A dictionary of East Durham Pitmatic spoken in Hetton-le-Hole, compiled by Rev. Francis M. T. Palgrave, was published in 1896[12] and reprinted in 1997.[13] The heritage society of nearby Houghton-le-Spring produced a list of words and phrases in 2017 collected over the preceding five years.[14] Harold Orton compiled a corpus (dataset) of dialect forms for 35 locations in Northumberland and northern Durham, known as the Orton Corpus.[15][16]

Pit Talk in County Durham, an illustrated, 90-page pamphlet by Dave Douglass, a local miner, was published in 1973.[17] In 2007, Bill Griffiths produced a dictionary of Pitmatic where each entry includes information on a word's etymology;[18] it was well reviewed.[19] In an earlier work,[20] Griffiths cited a newspaper of 1873 for the first recorded mention of the term "pitmatical".[2]

Vocabulary

[edit]Pitmatic words and expressions include:

- al reet* – alright, how are you?

- bait† – meal eaten underground

- byut* – boot

- chods* – lumps

- clarts* – mud

- dunch* – crash, bang together

- fyass* – face

- gan canny owwer the greaser† – mind how you go[i]

- ganning* – going

- gansey* – have a go

- had yer hand* – hold on a minute

- hoggers* – trousers

- hose† – pipe conveying compressed air

- impittent* – impudent

- jesting* – joking

- jigger† – vibrating trough for cleaning coal

- jowling† – tapping the wall or ceiling of a mine to check its condition

- keep had young'un* – take care

- knar* – know

- lektrishun† – electrician

- lugs* – ears

- maingate† – principal roadway in a mine

- marra* – mate, friend, work-mate

- netty* – toilet

- oot-by† – direction towards the mineshaft

- owwer* – over

- plodge* – to walk through mud or water

- rammel† – worthess stone mixed with coal

- rapping† – transmitting signals

- rive* – to tear or rip off

- shul* – shovel

- skeets† – guides for cages[ii] going up or down a mineshaft

- tadger† – electric drill

- tak had† – take hold, steady yourself (in the cage)

- thee* – your

- windy pick† – pneumatic pick

- winnet* – won't

- you're gettin yerself ahead of the buzzer† – getting above your station, being forward

- yummer* – bad mood

* from Houghton-le-Spring Heritage Society (2017)[14]

† from Griffiths (2007)[18]

Culture

[edit]Nowadays, the term "Pitmatic" is an falling out of popular usage.[citation needed]. In recent times, the dialect has underwent levelling and acquired features from more Standard English varieties. English as spoken in County Durham has been described as "half-Geordie, half-Teesside", and is quite accurately described in the article about Mackem.

In 2000, Melvyn Bragg presented a programme about Pitmatic on BBC Radio 4 as part of a series on English regional dialects.[21]

Pitmatic is heard in parts of the second episode of Ken Loach's 1975 series Days of Hope,[22] which was filmed around Esh Winning in Durham; the cast included local actor Alun Armstrong.

The poet, singer-songwriter and entertainer Tommy Armstrong worked mainly in Pitmatic and Geordie.[23] British comedian Bobby Thompson, popular across North East England, was famous for his Pitmatic accent.[24]

Related forms of English

[edit]Other Northern English dialects include:

- Cumbrian and Northumbrian dialects

- Yorkshire and Lancashire dialects

- Scouse (spoken in Merseyside)

- Mancunian (Spoken in Manchester)

See also

[edit]- English language in Northern England – Modern Northern English accents and dialects

- Northumbrian dialect – Any of several English dialects spoken in Northumbria, England

Notes

[edit]- ^ The greaser was a mechanism installed between the rails of the mine railway that lubricated the wheels of coal-carrying tubs.

- ^ A cage suspended on a wire rope is a conveyance used for moving workers and supplies below the surface of a mine.

References

[edit]- ^ Adapted from map on p. 203 of Redmayne, R. A. S. (October 1903). "The Coal-Mining Industry of the United Kingdom. II: Recent Development in British Coal-Mining". Engineering Magazine. 26 (2): 193–204. Retrieved 20 September 2024 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b c A Man on the Streets (19 April 1873). "Amongst the People". Newcastle Weekly Chronicle – Supplement. p. 4, col. 6 – via British Newspaper Archive.

A great many of the lads, especially from the Durham district, [...] [used] the purest 'pitmatical', shouted across the streets, [...].

- ^ Sadgrove, Michael (3 July 2005). Mining for Wisdom (sermon). The Ordination of Deacons. Durham Cathedral. Archived from the original on 23 May 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ Robinson, Jonnie (24 April 2019). "Geordie: A regional dialect of English". British Library. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ Påhlsson, Christer (1972). "The Northumbrian Burr: A Sociolinguistic Study". Lund studies in English. 41.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "The New Electorate". The Times. No. 31531. 21 August 1885. p. 4, col. 6. (At the Oakenshaw pit in County Durham): "[A]fter a few minutes delay in the overman's cabin, thronged with men talking an unintelligible language known, I was informed, as Pitmatic, we took our places".

- ^ Hitchin, George (1962). "Chapter IV: 'The People Who Walked in Darkness'". Pit-Yacker. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 70 (Seaham Colliery, c. 1910): "I was also acquiring a new language. This was 'pitmatic'. It was a mixture of the broadest dialect of Durham and a number of words (often of foreign origin) used exclusively by pitmen when below ground". OCLC 3789510 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Priestly, J. B. (1934). "Chapter Ten: To East Durham and the Tees". English Journey. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 265–266. OCLC 69655102 – via Internet Archive.

The local miners have a curious lingo [...] which they call 'pitmatik.' It is [...] a dialect within a dialect, for it is only used by the pitmen when they are talking among themselves. The women do not talk it. When the pitmen are exchanging stories of colliery life, [...] they do it in 'pitmatik,' which is Scandinavian in origin, far nearer to the Norse than the ordinary Durham dialect.

- ^ Beal, Joan C.; Burbano-Elizondo, Lourdes; Llamas, Carmen (2012). Urban North-Eastern English: Tyneside to Teesside. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-748-64152-9. OCLC 793582295.

- ^ a b Ellis, Alexander J. (1889). "On Early English Pronunciation, with Especial Reference to Shakspere and Chaucer : Part V, Existing Dialectical as Compared to West Saxon Pronunciation". London: Trübner for the Philological Society, the Early English Text Society, and the Chaucer Society. Retrieved 13 July 2024 – via Internet Archive. p. 641:

Var. iv, se.Nb. [...] This variety contains the speech of the Pitmen, and is most characteristic of Nb. But the mere writing of this speech conveys very little notion of its peculiarities of intonation, [...].The singsong and musical drawl of the pitmen must be heard to be understood. It is this variety to which the numerous dialectal books, annuals, comic stories, and songs usually refer.

- ^ Heslop, Richard Oliver. Northumberland Words. A Glossary of Words Used in the County of Northumberland and on the Tyneside. Volume I (A to F) (1892). Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & co. for the English Dialect Society – via Internet Archive. Volume II (G to Z) (1894). Henry Frowde, Oxford University Press for the English Dialect Society – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Palgrave, Rev. Francis Milnes Temple (1896). A List of Words and Phrases in Every-Day Use by the Natives of Hetton-Le-Hole in the County of Durham, Being Words not Ordinarily Accepted, or But Seldom Found in the Standard English of the Day (pdf, doc). London: Henry Frowde for the English Dialect Society. OCLC 163056065. Retrieved 24 June 2024. Via The Salamanca Corpus Digital Archive of English Dialect Texts

- ^ Palgrave, Rev. Francis Milnes Temple; Ridley, David (foreword) (1997) [1896]. Hetton-le-Hole Pitmatic Talk 100 Years Ago: a Dialect Dictionary of 1896. Gateshead: Johnstone-Carr. ISBN 978-0-953-14020-6. OCLC 41358108.

- ^ a b "We're Not Mackems: A Pitmatic Dictionary" (PDF). Houghton-le-Spring Heritage Society. January 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Rydland, Kurt (January 1992). "The Orton Corpus. A collection of dialect material from the north-east of England". Anglia. Journal of English Philology. 110: 1–35. doi:10.1515/angl.1992.1992.110.1. Retrieved 28 June 2024.

- ^ Rydland, Kurt (1998). The Orton Corpus: a Dictionary of Northumbrian Pronunciation 1928-1939. Oslo: Novus forlag. ISBN 978-8-270-99306-2. OCLC 40847001. Vol. 10 of Studia Anglistica Norvegica, ISSN 0333-4791.

- ^ Douglass, Dave (1973). "Pit Talk in County Durham: A Glossary of Miners' Talk together with Memories of Wardley Colliery, Pit Songs and Piliking". Oxford: History Workshop. OCLC 990097. Retrieved 25 June 2024.

- ^ a b Griffiths, Bill (2007). Pitmatic: The Talk of the North East Coalfield. Newcastle upon Tyne: Northumbria University Press. ISBN 978-1-904-79425-7.

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (30 July 2007). "Lost language of Pitmatic gets its lexicon". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

His new book reveals an exceptionally rich combination of borrowings from Old Norse, Dutch and a score of other languages, with inventive usages dreamed up by the miners themselves.

- ^ Griffiths, Bill (2004). "Historical introduction". A Dictionary of North East Dialect (first ed.). Newcastle upon Tyne: Northumbria University. pp. xvii–xviii. ISBN 978-1-904-79406-6 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Bragg, Melvyn (23 November 2000). "Pitmatic". The Routes of English. Series 3. BBC Radio 4 . Retrieved 27 June 2024.

- ^ Loach, Ken (18 September 1975). "1921". Days of Hope. BBC One. Retrieved 27 June 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Detective work reveals the true coalfield bard". Darlington & Stockton Times. 10 December 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Reviewer, Young (12 June 2013). "Review: The Bobby Thompson Story, Theatre Royal Newcastle". Chronicle Live. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Wales, Katie (2006). "Chapter 4: Northern English after the Industrial Revolution (1750–1950)". Northern English: A Social and Cultural History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 115–159. ISBN 978-0-521-86107-6. OCLC 271787609. Describes the socioeconomic roots and cultural context of northern dialects of English, with Pitmatic mentioned on pages 124-125.

External links

[edit]- Den Cutt's list of "Old Words & Phrases, Commonly Known as Pitmatic", from County Durham

- Fred Wade's Pitmatic word list, from South Moor, and Georgie McBurnie's "Pitman's Glossary", from Washington, hosted by the Durham & Tyneside Dialect Group

- "Yam", a poem in Pitmatic read by its author, Douglas Kew – via YouTube

- "Jowl, Jowl and Listen": film of miners from the Durham and Northumberland coalfields talking in dialect about their work and lives – via Vimeo