46P/Wirtanen

Wirtanen at perihelion on 12 December 2018 | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Carl A. Wirtanen |

| Discovery date | January 17, 1948 |

| Designations | |

| 1961 IV; 1960m; 1967 XIV; 1967k; 1974 XI; 1974i; 1986 VI; 1985q; 1991 XVI; 1991s; 46P/1948 A1; 1947 XIII; 1948b; 46P/1954 R2; 1954 XI; 1954j | |

| Orbital characteristics[1] | |

| Epoch | 2023-02-25 (JDT 2460000.5) |

| Aphelion | 5.127 AU |

| Perihelion | 1.055 AU |

| Semi-major axis | 3.091 AU |

| Eccentricity | 0.65867 |

| Orbital period | 5.43 yr |

| Inclination | 11.749° |

| Last perihelion | December 12, 2018[1] July 9, 2013[2] February 2, 2008 |

| Next perihelion | 2024-May-19[1] |

| Earth MOID | 0.071 AU (10,600,000 km)[3] |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 1.4 km (radar)[4] |

| 8.9 hours[4] | |

| Perihelion distance at different epochs[5] | |||||||

| Epoch | Perihelion (AU) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | 1.61 | ||||||

| 1974 | 1.26 | ||||||

| 1986 | 1.08 | ||||||

| 2013 | 1.05 | ||||||

| 2035 | 1.08 | ||||||

| 2046 | 1.22 | ||||||

| 2059 | 1.98 | ||||||

| 2095 | 2.01 | ||||||

46P/Wirtanen is a small short-period comet with a current orbital period of 5.4 years.[6][7] It was the original target for close investigation by the Rosetta spacecraft, planned by the European Space Agency, but an inability to meet the launch window caused Rosetta to be sent to 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko instead.[8] It belongs to the Jupiter family of comets, all of which have aphelia between 5 and 6 AU. Its diameter is estimated at 1.4 kilometres (0.9 mi). In December 2019, astronomers reported capturing an outburst of the comet in substantial detail by the TESS space telescope.[6][7]

Discovery

[edit]46P/Wirtanen was discovered photographically on January 17, 1948, by the American astronomer Carl A. Wirtanen.[9] The plate was exposed on January 15 during a stellar proper motion survey for the Lick Observatory. Due to a limited number of initial observations, it took more than a year to recognize this object as a short-period comet.

Perihelion passages

[edit]The July 2013 perihelion passage was not favorable, only reaching a magnitude of 14.7.[10] Between January 23 and September 26 of 2013, the comet had an elongation less than 20 degrees from the Sun.

On 16 December 2018 the comet passed 0.07746 AU (11.6 million km; 7.20 million mi; 30.1 LD) from Earth,[3] marking one of the 10 closest comet flybys of Earth in 70 years.[11] The comet reached an estimated magnitude of 3.9,[12] making this pass the brightest one predicted, and the brightest close approach for the next 20 years.[10] The comet experienced six outbursts, with the comet brightening by −0.2 to −1.6 magnitudes.[13]

The 2018 close approach, combined with Wirtanen's brightness provides an opportunity to study a potential future spacecraft mission target in detail. A worldwide observing campaign[14] was organized to capitalize on the favorable circumstances of the 2018 apparition.

-

Path of 46P across the sky during 2018. Its size shown is inversely proportional to its distance.

-

Orbital approach of 46P during 2018, moving south to north and crossing the ecliptic near its closest approach to Earth on December 16, 2018

-

Amateur astronomical image of Comet 46P on 12 December 2018

-

View from the Hubble Space Telescope on December 13, 2018

-

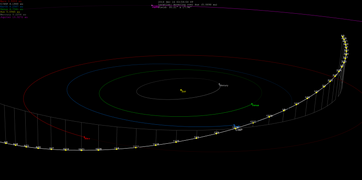

File:Animation of 46P/Wirtanen orbit

Sun · Mercury · Venus · Earth · Mars · Jupiter · 46P/Wirtanen

Exploration proposals

[edit]

The comet was the target for the proposed Comet Hopper mission, which reached the finalist stage in the NASA Discovery program. It was one of only three missions in that selection to have a more detailed study. The selection process was ultimately won in 2012 by the InSight mission, a Mars lander. The Comet Hopper was designed to use the ASRG, the Advanced Stirling Radioisotope Generator.

The Comet Hopper mission, if it were selected, would have had multiple science goals over the 7.3 years of its nominal lifetime. At roughly 4.5 AU the spacecraft would rendezvous with Comet Wirtanen and begin to map the spatial heterogeneity of surface solids as well as gas and dust emissions from the coma - the nebulous envelope around the nucleus of a comet. The remote mapping would also allow for any nucleus structure, geologic processes, and coma mechanisms to be determined. After arriving at the comet, the spacecraft would approach and land, then subsequently hop to other locations on the comet. As the comet approached the Sun, the spacecraft would land and hop multiple times.[16] The final landing would occur at 1.5 AU. As the comet approached the Sun and became more active, the spacecraft would be able to record surface changes.[17]

Also, 46P/Wirtanen was the original destination of the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft mission, but launch delays meant that the comet was no longer easily reachable and another periodic comet, 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, was chosen as the mission's target instead.[18][19]

Associated meteor showers

[edit]2023

[edit]Close approaches to Jupiter in 1972 and 1984 moved the comet's orbit closer to Earth, and as of epoch 2018 the comet has an Earth–MOID of 0.071 AU (10.6 million km; 6.6 million mi; 28 LD).[3] In 2023 Earth passed through a denser part of the 1974 meteoroid stream than Earth did in 2007.[20] As a result a shower with radiant in the southern constellation of Sculptor was observed with a zenithal hourly rate (ZHR) of 0.65+0.24

−0.20 and was given the name λ-Sculptorids. The meteors made atmospheric entry (Ve) at a relatively slow 15 km/s and as a result the mean mass of the meteoroids observed was about 0.5 grams, about 10 times higher than that of other meteor showers.[21]

| Date | Stream |

|---|---|

| 2007 | 1974 |

| 2018 | 1980 |

| 2023-December-12 10:54 UT | 1974 |

2012

[edit]Russian forecaster Mikhail Maslov had predicted that the Earth's orbit would cross Comet Wirtanen's debris stream as many as four times between December 10 and December 14, 2012. As there had not previously been an encounter with this debris stream, it was not certain whether or not a meteor shower would be visible from Earth, but there was speculation that a shower with as many as 30 meteors per hour might occur.[22]

Observers in Australia reported that on the night of December 14, 2012, as many as a dozen meteors were seen emanating from the predicted radiant in the constellation of Pisces.[23]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "46P/Wirtanen Orbit". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ Syuichi Nakano (2010-04-09). "46P/Wirtanen (NK 1909)". OAA Computing and Minor Planet Sections. Retrieved 2012-02-18.

- ^ a b c "JPL Small-Body Database: 46P/Wirtanen" (last observation: 2019-07-01; arc: 1.15 years). Archived from the original on 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ a b "UA Researcher Captures Rare Radar Images of Comet 46P/Wirtanen". 20 December 2018.

- ^ Kinoshita, Kazuo (2019-06-09). "46P/Wirtanen past, present and future orbital elements". Comet Orbit. Archived from the original on 2012-04-22. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ a b Goddard Space Flight Center (3 December 2019). "NASA's exoplanet-hunting mission catches a natural comet outburst in unprecedented detail". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ a b University of Maryland (3 December 2019). "UMD astronomers catch a natural comet outburst in unprecedented detail - Data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) reveal start-to-finish sequence of an outburst from comet 46P/Wirtanen". EurekAlert!. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ^ Ulamec, S.; Espinasse, S.; Feuerbacher, B.; Hilchenbach, M.; Moura, D.; et al. (April 2006). "Rosetta Lander—Philae: Implications of an alternative mission". Acta Astronautica. 58 (8): 435–441. Bibcode:2006AcAau..58..435U. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2005.12.009.

- ^ Kronk, Gary W. "46P/Wirtanen". Retrieved 2019-03-03. (Cometography Home Page)

- ^ a b "Comet 46P/Wirtanen Information". theskylive.com. Retrieved 2017-11-26.

- ^ "See a Passing Comet This Sunday". JPL. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- ^ "Brightest comets seen since 1935". www.icq.eps.harvard.edu. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ Kelley, Michael S. P.; Farnham, Tony L.; Li, Jian-Yang; Bodewits, Dennis; Snodgrass, Colin; et al. (1 August 2021). "Six Outbursts of Comet 46P/Wirtanen". The Planetary Science Journal. 2 (4): 131. arXiv:2105.05826. Bibcode:2021PSJ.....2..131K. doi:10.3847/PSJ/abfe11.

- ^ "The Comet Wirtanen Observing Campaign". wirtanen.astro.umd.edu. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ^ "Picturesque poison". www.eso.org. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- ^ "Maryland scientists vie for NASA missions". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 2012-09-26. Retrieved 2011-06-02.

- ^ "Planetary Science Division Update" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-11-14. Retrieved 2011-05-23.

- ^ "Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko". Rosetta. ESA. 18 December 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ "Hubble Assists Rosetta Comet Mission" (Press release). Hubble Space Telescope. September 5, 2003. Retrieved May 20, 2014.

- ^ a b "A new meteor shower caused by comet 46P/Wirtanen". IMCCE. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ Vida, D.; Scott, J. M.; Egal, A.; Vaubaillon, J.; Ye, Q.-Z.; Rollinson, D.; Sato, M.; Moser, D. E. (February 2024). "Observations of the new meteor shower from comet 46P/Wirtanen". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 682: L20. arXiv:2402.07769. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202449359.

- ^ "A New Meteor Shower in December?". NASA. Archived from the original on 2012-12-12. Retrieved 2012-12-13.

- ^ "Comet Wirtanen meteors report". IceInSpace. Retrieved 2012-12-17.

External links

[edit]- IAU Ephemerides page for 46P

- 46P on JPL Small-Body Database Browser

- 46P/Wirtanen – Seiichi Yoshida @ aerith.net