Xi Zhongxun

Xi Zhongxun | |

|---|---|

习仲勋 | |

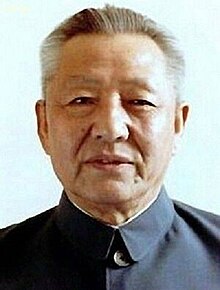

Xi in the 1990s | |

| Vice Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress | |

| In office 10 September 1980 – 15 March 1993 | |

| Chairman | Ye Jianying→Peng Zhen→Wan Li |

| Communist Party Secretary of Guangdong | |

| In office November 1978 – November 1980 | |

| Preceded by | Wei Guoqing |

| Succeeded by | Ren Zhongyi |

| Governor of Guangdong | |

| In office January 1979 – February 1981 | |

| Preceded by | Wei Guoqing (as Director of the Guangdong Provincial Revolutionary Committee) |

| Succeeded by | Liu Tianfu |

| 1st Secretary-General of the State Council | |

| In office September 1954 – January 1965 | |

| Premier | Zhou Enlai |

| Preceded by | Li Weihan |

| Succeeded by | Zhou Rongxin |

| 14th Head of the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party | |

| In office January 1953 – July 1954 | |

| Party Chairman | Mao Zedong |

| Preceded by | Lu Dingyi |

| Succeeded by | Lu Dingyi |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 October 1913 Fuping County, Shaanxi, Republic of China |

| Died | 24 May 2002 (aged 88) Beijing, People's Republic of China |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party (joined in 1928) |

| Other political affiliations | Kuomintang (1937–1945) |

| Spouse(s) | Hao Mingzhu Qi Xin |

| Children | 7, including Qi Qiaoqiao, Xi Jinping and Xi Yuanping |

| Xi Zhongxun | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 习仲勋 | ||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 習仲勲 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Xi Zhongxun (Chinese: 习仲勋; pinyin: Xí Zhòngxūn; 15 October 1913 – 24 May 2002) was a Chinese communist revolutionary and a subsequent political official in the People's Republic of China. He is considered to be among the first and second generation of Chinese leadership.[1] The contributions he made to the Chinese communist revolution and the development of the People's Republic, from the founding of Communist guerrilla bases in northwestern China in the 1930s to initiation of economic liberalization in southern China in the 1980s, are numerous and broad. He was known for political moderation and for the setbacks he endured in his career. He was imprisoned and purged several times. His second son, Xi Jinping, is the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party since 2012.

Early life and education

[edit]Xi was born on 15 October 1913, to a land-owning family, in rural Fuping County, Shaanxi.[2] His parents, Xi Zongde and Chai Caihua, died when he was a teenager.[3] He joined the Chinese Communist Youth League in May 1926 and took part in student demonstrations in the spring of 1928, for which he was imprisoned by the ruling nationalist authorities.[2] In prison, he joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1928.[2]

Career

[edit]Red Army

[edit]In 1930, Xi was appointed by the party to work in the Guominjun under Yang Hucheng.[4] In March 1932, he led an unsuccessful uprising within that army in Liangdang, Gansu.[2][5] Subsequently, he joined Communist guerrillas north of the Wei River.[2] In March 1933, he joined Liu Zhidan and others in founding the Shaanxi–Gansu (Shaangan) Border Region Soviet Area, and became the chairman of the Soviet area government while leading guerillas in resisting Nationalist incursions and expanding the Soviet area.[2] In early 1935, the Shaanxi–Gansu Border and Northern Shaanxi Soviet Areas merged to form the Revolutionary Base Area of the Northwest and Xi became one of the leaders of the base area.[2] But in September 1935, he along with Liu Zhidan and Gao Gang were jailed during a Leftist rectification campaign within the party.[2] By his own account, he was within four days of being executed when CCP Chairman Mao Zedong arrived on the scene and ordered Xi and his comrades released.[6] Xi's guerrilla base in the Northwest gave refuge to Mao Zedong and the party center, and allowed them to end the Long March. It is said that Xi's "Revolutionary Base Area of the Northwest saved the Party Center and the Party Center saved the revolutionaries of the Northwest."[6] The base area eventually became the Yan'an Soviet, the headquarters of the Chinese Communist movement until 1947.

Sino-Japanese War

[edit]During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Xi stayed in the Yan'an Soviet to manage civilian and military affairs, boost economic production within the Soviet, and implement party policies.[2] He was known for evaluating policies based on empirical assessment and resisting "leftist" extremism in implementing party directives.[2] At the 7th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in August 1945, he was named an alternate member of the Central Committee and became the deputy director of the party's organization department, in charge of making personnel decision.[2] As World War II in China was winding down, he defeated a Nationalist attack on the Yan'an Soviet at Futaishan and assisted the breakout of Wang Zhen's 359 Brigade from the North China Plains.[2]

Chinese Civil War and post-war transition

[edit]

With the outbreak of full-scale civil war between Communists and Nationalists in early 1947, Xi remained in northwestern China to coordinate the protection and then recapture of the Yan'an Soviet Area.[2] As political commissar, Xi and commander Zhang Zongxun defeated Nationalists west of Yan'an at the Battle of Xihuachi in March 1947.[2] After Yan'an fell to Hu Zongnan on 19 March 1947, Xi worked on the staff of Peng Dehuai in the battles to retake Yan'an and capture northwest China.[2]

Xi directed the political work of the Northwest Political and Military Affairs Bureau, which was tasked with bringing Communist governance to the newly captured areas of the Northwest.[2] In this capacity, Xi was known for his moderate policies and the use of non-military means to pacify rebellious areas.[2]

Xi was sometimes critical of the land reform movement,[7] and was an advocate for the position of the middle peasantry.[8] As violence increased in 1948, Xi reported that activists in the northwest had sometimes falsely designated landlords and manufactured struggle.[7] In 1952, Xi Zhongxun halted the campaign of Wang Zhen and Deng Liqun to implement land reform and class struggle to pastoralist regions of Xinjiang.[9] Xi, based on experience in Inner Mongolia, advised against assigning class labels and waging class struggle among pastoralists, but was ignored by Wang and Deng who directed the seizure of livestock from landowners and land from religious authorities.[9] The policies inflamed social unrest in pastoralist northern Xinjiang where Ospan Batyr uprising had just been quelled.[9] With the support of Mao, Xi reversed the policies, had Wang Zhen relieved from Xinjiang and released over a thousand herders from prison.[9]

In July 1951, following the Communists' defeat of the Ma Clique armies in Qinghai, remnants of the Muslim warlords incited rebellion among Tibetan tribesmen.[10] Among those who took up arms was chieftain Xiang Qian of the Nganglha Tribe in eastern Qinghai.[10] As the PLA sent troops to quell the uprising, Xi Zhongxun urged for a political solution.[10] Numerous envoys including Geshe Sherab Gyatso and the Panchen Lama went to negotiate.[10] Though Xiang Qian rebuffed dozens of offers and the PLA managed to capture the chieftain's villages, Xi continued to pursue a political solution.[10] He released captured tribesmen, offered generous terms to Xiang Qian and forgave those who took part in the uprising.[10] In July 1952, Xiang Qian returned from hiding in the mountains, pledged his allegiance to the People's Republic and was invited by Xi to attend the graduation ceremony of the Nationalities College in Lanzhou.[10] In 1953, Xiang Qiang became the chief of Jainca County. Mao compared Xi's deft treatment of Xiang Qian to Zhuge Liang's conciliation of Meng Huo in the Romance of the Three Kingdoms.[citation needed]

When the 14th Dalai Lama visited Beijing in 1954 for several months of political meetings and studies in Chinese and Marxism, Xi spent time with the Tibetan leader, who fondly recalled Xi as "very friendly, comparatively open-minded, very nice."[11] As a gift, the Dalai Lama gave Xi an Omega watch.[12] When the Dalai Lama's brother visited Beijing in the early 1980s, Xi was still wearing that watch.[12]

High offices in Beijing, purge

[edit]

In September 1952, Xi Zhongxun became chief of the party's propaganda department and supervised cultural and education policies.[13] At the 8th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in 1956, he was elected a member of the CCP Central Committee.[13] In 1959, he became a vice-premier and worked under Premier Zhou Enlai in directing the State Council's lawmaking and policy research functions.[13]

In 1962, he was accused by Kang Sheng of leading an anti-party clique for supporting the Biography of Liu Zhidan, and purged from all leadership positions.[13] The biography, written by Li Jiantong (李建彤) to commemorate Xi's former comrade who died a party martyr in 1936, was alleged to be a covert effort to subvert the party by rehabilitating Gao Gang, another former comrade who had been purged in 1954. Xi Zhongxun was forced to undergo self-criticism and in 1965 was demoted to the position of a deputy manager of a tractor factory in Luoyang.[14] During the Cultural Revolution, he was persecuted, jailed and spent long periods in confinement in Beijing.[14] He regained his freedom in May 1975 and was assigned to another factory in Luoyang.[14]

As Guangdong's top official

[edit]After the Cultural Revolution ended, Xi was fully rehabilitated at the Third Plenary Session of the 11th CCP Central Committee in December 1978.[13] From 1978 to 1981, he held leadership roles in Guangdong Province, successively as the second and then first provincial secretary, governor and political commissar of the Guangdong Military Region.[13] In Guangdong, he stabilized the provincial government and began to liberalize the economy.[13]

When he first arrived in Guangdong, he was told the provincial government had long been struggling to hold back the exodus of Chinese to Hong Kong since 1951.[15][16] At the time, daily wages in Guangdong averaged 0.70 yuan, about 1/100 of wages in Hong Kong.[16] Xi understood the disparity in standards of living and called for economic liberalisation in Guangdong.[16] To do so, he needed to win over leaders in Beijing skeptical of the market economy. In meetings in April 1979, he convinced Deng Xiaoping to permit Guangdong to make its own foreign trade policy decisions and to invite foreign investment to projects in experimental areas along the provincial border with Hong Kong and Macau and in Shantou, which has a large overseas diaspora.[17] As for the name of the experimental areas, Deng said, "let's call them, 'special zones', [after all, your] Shaanxi-Gansu Border Region began as a 'special zone'."[17] Deng added, "The Central Government has no funds, but we can give you some favorable policies." Borrowing a phrase from their guerrilla war days, Deng told Xi, "You have to find a way, to fight a bloody path out."[17] Xi submitted a formal proposal on the creation of special zones, later renamed special economic zones and in July 1979, the party center and State Council approved the creation of the first four special economic zones.[16][17]

Retirement

[edit]In 1981, Xi returned to Beijing and was elected the deputy chair of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress and also held the chair of the legal affairs committee.[13] In this capacity, he oversaw the drafting of numerous laws.[13] In September 1982, he was elected to the CCP Politburo and the CCP secretariat.[13] In 1987, Deng Xiaoping and powerful elder Chen Yun were dissatisfied with the liberal inclination of Hu Yaobang, and called a meeting to force Hu to resign as CCP General Secretary. Xi was the only one that defended Hu. Xi retired from public service in March 1993 and spent most of his retirement years in Shenzhen.[13][16]

Xi Zhongxun attended the 50th anniversary of the People's Republic of China in Beijing in October 1999.

Personal life and death

[edit]In 1936, Xi married Hao Mingzhu, the niece of revolutionary fighter Wu Daifeng, in Shaanxi. The union lasted until 1944, and the couple had three children: one son, Xi Fuping (aka Xi Zhengning), and two daughters, Xi Heping, and Xi Ganping.[18] According to official records, Xi Heping died during the Cultural Revolution due to persecution, which historians have concluded means that she most likely committed suicide under duress.[19] Little is known about Xi Ganping, except that she was retired by 2013 and regularly appears at meetings of Princelings. Xi Zhengning, meanwhile, was a researcher in the Ministry of Defence but later pursued a bureaucratic career; he died in 1998.[20]

In 1944, Xi Zhongxun married Qi Xin, his second wife, and had four children: Qi Qiaoqiao, Xi An'an, Xi Jinping and Xi Yuanping. Xi Jinping became the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and Chairman of the Central Military Commission, thus the paramount leader of China, from 15 November 2012, and has been President of the People's Republic of China since March 2013.

Xi Zhongxun died 24 May 2002. His funeral and subsequent cremation at Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery on 30 May was attended by party and state leaders, including President Jiang Zemin, Premier Zhu Rongji, and Vice President Hu Jintao. His ashes were subsequently buried at a cemetery named in honor of him at Fuping County.[13][21]

His official obituary described him as "an outstanding proletarian revolutionary," "a great communist soldier," and "one of the main founders and leaders of the revolutionary base areas in the Shaanxi-Gansu border region."

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Đình Nguyễn. "Tập Cận Bình – 'Lãnh đạo tương lai' của Trung Quốc" (in Vietnamese). Vnexpress. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q 习仲勋的故事(全本)前中央书记处书记习仲勋的战斗一生 - 第1章 习仲勋生平(1) (in Chinese (China)). Ifeng Books. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ Sheridan, Michael (2024). The Red Emperor: Xi Jinping and His New China. London, U.K.: Headline Press. p. 20. ISBN 9781035413485.

His father, Zi Zongde, died in his early forties, when the boy was a teenager. His mother, Chai Caihua, lived only a year longer.

- ^ "《习仲勋的故事》_共产党员网". fuwu.12371.cn. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ 晨雨 (Chenyu), 杨 (Yang) (11 June 2009). "两当兵变的特点和历史地位-两当|兵变|特点|历史地位-每日甘肃-陇南日报 (The characteristics and the historical status of the Liangdang Uprising)". Archived from the original on 11 May 2019.

- ^ a b He, Libo (何立波); Ma, Hongmin (马红敏). "英雄一世,坎坷一生”的习仲勋" 中国共产党新闻>>党史频道>>人物长廊. people.cn (in Chinese (China)). Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ a b DeMare, Brian James (2019). Land wars : the story of China's agrarian revolution. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-5036-0849-8. OCLC 1048940018.

- ^ DeMare, Brian James (2019). Land wars : the story of China's agrarian revolution. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-1-5036-0849-8. OCLC 1048940018.

- ^ a b c d "王震新疆镇反被撤职幕后". 21cn.com (in Chinese (China)). 7 July 2009. Archived from the original on 17 August 2011. Retrieved 19 February 2012. 7 July 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g Zhang, Shaowu (张绍武); Guo, Suqiang (郭素强) (9 September 2011). "昂拉平叛与争取项谦的经过". hhwhjj.com (Yellow River Culture and Economy online) (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2012. 9 September 2011

- ^ Benjamin K. Lim & Frank J. Daniel, "Does China's next leader have a soft spot for Tibet?" Reuters 1 September 2012

- ^ a b Pramit Pal Chaudhuri, "Tibet's conquest of China's Xi Jinping family" Hindustan Times Archived 13 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine 4 February 2013

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l 习仲勋的故事(全本)前中央书记处书记习仲勋的战斗一生 - 第1章 习仲勋生平(2) (in Chinese (China)). Ifeng Books. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ^ a b c 习仲勋蒙受不白之冤]. crt.com.cn (Zhonghongwang) (in Chinese (China)). Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 19 February 2012. Accessed 19 February 2012

- ^ Chen Bing'an [陳秉安] (2016). 大逃港(增訂本) [The Great Exodus to Hong Kong (Revised edition)] (in Chinese). Hong Kong Open Page. p. 371-389.

- ^ a b c d e 习仲勋:我要看着深圳发展 (in Chinese (China)). Sina News. 25 August 2010.

- ^ a b c d 谷梁 "习仲勋主政广东的历史功绩:改革开放天下先 (6)". people.cn (Renminwang) (in Chinese (China)). 21 January 2012.

- ^ Andrésy 2016, p. 8.

- ^ Buckley, Chris; Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (24 September 2015). "Cultural Revolution Shaped Xi Jinping, From Schoolboy to Survivor". New York Times. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Andrésy 2016, p. 9.

- ^ "Dozens Detained in Bid To Visit Grave of Chinese President's Father". Radio Free Asia. 5 April 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

Sources

[edit]- Andrésy, Agnès (2016). Xi Jinping: Red China, the Next Generation. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. ISBN 9780761866015.

- China's New Rulers: The Secret File, Andrew J. Nathan and Bruce Gilley, The New York Review Book

- The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, Vol. 3 : The Coming of the Cataclysm, 1961-1966 (Columbia University Press, 1997)

External links

[edit]- Biography of Xi Zhongxun, China Vitae

- (in Chinese) Biography of Xi Zhongxun

- Vice premiers of the People's Republic of China

- 1913 births

- 2002 deaths

- Chinese revolutionaries

- Chinese Communist Party politicians from Shaanxi

- Governors of Guangdong

- Heads of the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party

- Members of the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party

- People's Republic of China politicians from Shaanxi

- Politicians from Weinan

- Family of Xi Jinping

- Members of the 12th Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party

- Vice Chairpersons of the National People's Congress

- Victims of the Cultural Revolution