Exploration of the Moon

The physical exploration of the Moon began when Luna 2, a space probe launched by the Soviet Union, made a deliberate impact on the surface of the Moon on September 14, 1959. Prior to that the only available means of lunar exploration had been observations from Earth. The invention of the optical telescope brought about the first leap in the quality of lunar observations. Galileo Galilei is generally credited as the first person to use a telescope for astronomical purposes, having made his own telescope in 1609, the mountains and craters on the lunar surface were among his first observations using it.

Human exploration of the moon since Luna 2 has consisted of both crewed and uncrewed missions. NASA's Apollo program has been the only program to successfully land humans on the Moon, which it did six times on the near side in the 20th century. The first human landing took place in 1969, when the Apollo 11 astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Neil Armstrong touched down on the lunar surface, leaving scientific instruments upon the mission's completion and returning lunar samples to Earth.[1] All missions had taken place on the lunar near side until the first soft landing on the far side of the Moon was made by the CNSA robotic spacecraft Chang'e 4 in early 2019, which successfully deployed the Yutu-2 robotic lunar rover.[2][3] On 25 June 2024, China's Chang'e 6 conducted the first lunar sample return from the far side of the Moon.[4]

The current goals of lunar exploration across all major space agencies now primarily focus on the continued survey of the lunar surface through various lunar missions in preparation for the eventual establishment of non-temporary human outposts.[5]

Pre-telescopic

[edit]It is believed by some that the oldest cave paintings from up to 40,000 BP of bulls and geometric shapes,[6] or 20–30,000 year old tally sticks were used to observe the phases of the Moon, keeping time using the waxing and waning of the Moon's phases.[7] One of the earliest known possible depictions of the Moon is a 3,000 BCE rock carving Orthostat 47 at Knowth, Ireland.[8][9] Lunar deities like Nanna/Sin featuring crescents are found since the 3rd millenium BCE.[10] Though the oldest found and identified astronomical depiction of the Moon is the Nebra sky disc from c. 1800–1600 BCE.[11][12]

The ancient Greek philosopher Anaxagoras, whose non-religious view of the heavens was one cause for his imprisonment and eventual exile,[16] reasoned that the Sun and Moon were both giant spherical rocks, and that the latter reflected the light of the former. Plutarch, in his book On the Face in the Moon's Orb, suggested that the Moon had deep recesses in which the light of the Sun did not reach and that the spots are nothing but the shadows of rivers or deep chasms. He also entertained the possibility that the Moon was inhabited. Aristarchus attempted to compute the Moon's size and distance from Earth, although his estimated distance of 20 times Earth's radius (which had been accurately determined by his contemporary Eratosthenes) proved to be about a third the actual average distance.

Chinese philosophers of the Han dynasty believed the Moon to be energy equated to qi but recognized that the light of the Moon was a reflection of the Sun.[17] Mathematician and astrologer Jing Fang noted the sphericity of the Moon.[17] Shen Kuo of the Song dynasty created an allegory equating the waxing and waning of the Moon to a round ball of reflective silver that, when doused with white powder and viewed from the side, would appear to be a crescent.[17]

Indian astronomer Aryabhata stated in his fifth-century text Aryabhatiya that reflected sunlight is what causes the Moon to shine.[18]

Persian astronomer Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi conducted various observations at the Al-Shammisiyyah observatory in Baghdad between 825 and 835.[19] Using these observations, he estimated the Moon's diameter as 3,037 km (equivalent to 1,519 km radius) and its distance from the Earth as 346,345 km (215,209 mi).[19] In the 11th century, the Islamic physicist Alhazen investigated moonlight through a number of experiments and observations, concluding it was a combination of the Moon's own light and the Moon's ability to absorb and emit sunlight.[20][21]

By the Middle Ages, before the invention of the telescope, an increasing number of people began to recognise the Moon as a sphere, though many believed that it was "perfectly smooth".[22]

Telescopic exploration before spaceflight

[edit]In 1609, Galileo Galilei drew one of the first telescopic drawings of the Moon in his book Sidereus Nuncius and noted that it was not smooth but had mountains and craters. Later in the 17th century, Giovanni Battista Riccioli and Francesco Maria Grimaldi drew a map of the Moon and gave many craters the names they still have today. On maps, the dark parts of the Moon's surface were called maria (singular mare) or seas, and the light parts were called terrae or continents.

Thomas Harriot, as well as Galilei, drew the first telescopic representation of the Moon and observed it for several years. His drawings, however, remained unpublished.[23] The first map of the Moon was made by the Belgian cosmographer and astronomer Michael van Langren in 1645.[23] Two years later a much more influential effort was published by Johannes Hevelius. In 1647, Hevelius published Selenographia, the first treatise entirely devoted to the Moon. Hevelius's nomenclature, although used in Protestant countries until the eighteenth century, was replaced by the system published in 1651 by the Jesuit astronomer Giovanni Battista Riccioli, who gave the large naked-eye spots the names of seas and the telescopic spots (now called craters) the name of philosophers and astronomers.[23]

In 1753, the Croatian Jesuit and astronomer Roger Joseph Boscovich discovered the absence of atmosphere on the Moon. In 1824, Franz von Paula Gruithuisen explained the formation of craters as a result of meteorite strikes.[24]

The now disproven possibility that the Moon contains vegetation and is inhabited by selenites was seriously considered by major astronomers of the early modern period even into the first decades of the 19th century. In 1834–1836, Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich Mädler published their four-volume Mappa Selenographica and the book Der Mond in 1837, which firmly established the conclusion that the Moon has no bodies of water nor any appreciable atmosphere.[25]

Space Race

[edit]The Cold War-inspired "space race" and "Moon race" between the Soviet Union and the United States of America accelerated with a focus on the Moon. This included many scientifically important firsts, such as the first photographs of the then-unseen far side of the Moon in 1959 by the Soviet Union, and culminated with the landing of the first humans on the Moon in 1969, widely seen around the world as one of the pivotal events of the 20th century and of human history in general.

The first artificial object to fly by the Moon was uncrewed Soviet probe Luna 1 on January 4, 1959, and went on to be the first probe to reach a heliocentric orbit around the Sun.[27] Few knew that Luna 1 was designed to impact the surface of the Moon.

The first probe to impact the surface of the Moon was the Soviet probe Luna 2, which made a hard landing on September 14, 1959, at 21:02:24 UTC. The far side of the Moon was first photographed on October 7, 1959, by the Soviet probe Luna 3. Though vague by today's standards, the photos showed that the far side of the Moon almost completely lacked maria.

The first American probe to fly by the Moon was Pioneer 4 on March 4, 1959, which occurred shortly after Luna 1. It was the only success of eight American probes that first attempted to launch for the Moon.[28]

In an effort to compete with these Soviet successes, U.S. President John F. Kennedy proposed the Moon landing in a Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs:

Now it is time to take longer strides – time for a great new American enterprise – time for this nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement, which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.

...For while we cannot guarantee that we shall one day be first, we can guarantee that any failure to make this effort will make us last.

...I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important in the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.

...let it be clear that I am asking the Congress and the country to accept a firm commitment to a new course of action—a course which will last for many years and carry very heavy costs...[29] Full text

Ranger 1 launched in August 1961, just three months after President Kennedy's speech. It would be three more years and six failed Ranger missions until Ranger 7 returned close up photos of the Lunar surface before impacting it in July 1964. A number of problems with launch vehicles, ground equipment, and spacecraft electronics plagued the Ranger program and early probe missions in general. These lessons helped in Mariner 2, the only successful U.S. space probe after Kennedy's famous speech to congress and before his death in November 1963.[30] U.S. success rates improved greatly from Ranger 7 onward.

In 1966, the USSR accomplished the first soft landings and took the first pictures from the lunar surface during the Luna 9 and Luna 13 missions.

The U.S. followed Ranger with the Surveyor program[31] sending seven robotic spacecraft to the surface of the Moon. Five of the seven spacecraft successfully soft-landed, investigating if the regolith (dust) was shallow enough for astronauts to stand on the Moon.

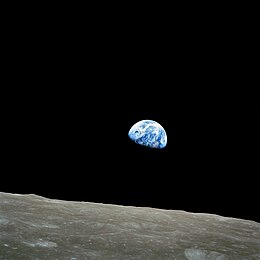

In September 1968 the Soviet Union's Zond 5 sent tortoises on a circumlunar mission, followed by turtles aboard Zond 6 in November. On December 24, 1968, the crew of Apollo 8—Frank Borman, James Lovell and William Anders—became the first human beings to enter lunar orbit and see the far side of the Moon in person. Humans first landed on the Moon on July 20, 1969. The first humans to walk on the lunar surface were Neil Armstrong, commander of the U.S. mission Apollo 11 and his fellow astronaut Buzz Aldrin.

The first robot lunar rover to land on the Moon was the Soviet vessel Lunokhod 1 on November 17, 1970, as part of the Lunokhod programme. To date, the last human to stand on the Moon was Eugene Cernan, who as part of the Apollo 17 mission, walked on the Moon in December 1972.

Moon rock samples were brought back to Earth by three Luna missions (Luna 16, 20, and 24) and the Apollo missions 11 through 17 (except Apollo 13, which aborted its planned lunar landing). Luna 24 in 1976 was the last Lunar mission by either the Soviet Union or the U.S. until Clementine in 1994. Focus shifted to probes to other planets, space stations, and the Shuttle program.

Before the "Moon race," the U.S. had pre-projects for scientific and military moonbases: the Lunex Project and Project Horizon. Besides crewed landings, the abandoned Soviet crewed lunar programs included the building of a multipurpose moonbase "Zvezda", the first detailed project, complete with developed mockups of expedition vehicles[32] and surface modules.[33]

After 1990

[edit]

Japan

[edit]In 1990, Japan's JAXA visited the Moon with the Hiten spacecraft, becoming the third country to place an object in orbit around the Moon. The spacecraft released the Hagoromo probe into lunar orbit, but the transmitter failed, thereby preventing further scientific use of the spacecraft. In September 2007, Japan launched the SELENE spacecraft, with the objectives "to obtain scientific data of the lunar origin and evolution and to develop the technology for the future lunar exploration", according to the JAXA official website.[34]

In 2023, Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) is a lunar lander mission of the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). By 2017, the lander was planned to be launched in 2021, but this was delayed until 2023 due to delays in SLIM's ride-share mission, X-Ray Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission (XRISM). It was successfully launched on 6 September 2023 at 23:42 UTC (7 September 08:42 Japan Standard Time). On 1 October 2023, the lander executed its trans-lunar injection burn. It entered orbit around the Moon on 25 December 2023, and landed on 19 January 2024 at 15:20 UTC. As a result, Japan became the fifth country to soft land on the surface of the Moon.[35] Since then, it has survived 4 lunar days and 3 lunar nights.[36]

European Space Agency

[edit]The European Space Agency launched a small, low-cost lunar orbital probe called SMART 1 on September 27, 2003. SMART 1's primary goal was to take three-dimensional X-ray and infrared imagery of the lunar surface. SMART 1 entered lunar orbit on November 15, 2004, and continued to make observations until September 3, 2006, when it was intentionally crashed into the lunar surface in order to study the impact plume.[37]

China

[edit]China has begun the Chinese Lunar Exploration Program for exploring the Moon and is investigating the prospect of lunar mining, specifically looking for the isotope helium-3 for use as an energy source on Earth.[38] China launched the Chang'e 1 robotic lunar orbiter on October 24, 2007. Originally planned for a one-year mission, the Chang'e 1 mission was very successful and ended up being extended for another four months. On March 1, 2009, Chang'e 1 was intentionally impacted on the lunar surface completing the 16-month mission. On October 1, 2010, China launched the Chang'e 2 lunar orbiter. China landed the rover Yutu and the Chang'e 3 lander on the Moon on December 14, 2013, became the third country to have done so.[39] Chang'e 3 is the first spacecraft to soft-land on lunar surface since Luna 24 in 1976. Since the Chang'e 3 mission was a success, the backup lander Chang'e 4 was re-purposed for the new mission goals. China launched on 7 December 2018 the Chang'e 4 mission to the lunar farside.[40] On January 3, 2019, Chang'e 4 landed on the far side of the Moon.[41] Chang'e 4 deployed the Yutu-2 Moon rover, which subsequently became the current record distance-holder for lunar surface travel.[42] Among other discoveries, Yutu-2 found that the dust at some locations of the far side of the Moon is up to 12 meters deep.[43]

China planned to conduct a sample return mission with its Chang'e 5 spacecraft in 2017, but that mission was postponed[44] due to the failure of the Long March 5 launch vehicle.[45] However, after a successful return of flight by the Long March 5 rocket in late December 2019, China targeted its Chang'e 5 sample return mission for late 2020.[46] China completed this mission on December 16, 2020, with the return of approximately 2 kilograms of lunar sample.[47]

China sent Chang'e 6 on 3 May 2024, which conducted the first lunar sample return from Apollo Basin on the far side of the Moon.[48] This is China's second lunar sample return mission, the first was achieved by Chang'e 5 from the lunar near side four years earlier.[49] It also carried a Chinese rover called Jinchan to conduct infrared spectroscopy of lunar surface and imaged Chang'e 6 lander on lunar surface.[50] The lander-ascender-rover combination was separated with the orbiter and returner before landing on 1 June 2024 at 22:23 UTC. It landed on the Moon's surface on 1 June 2024.[51][52] The ascender was launched back to lunar orbit on 3 June 2024 at 23:38 UTC, carrying samples collected by the lander, and later completed another robotic rendezvous and docking in lunar orbit. The sample container was then transferred to the returner, which landed on Inner Mongolia on 25 June 2024, completing China's far side extraterrestrial sample return mission.

India

[edit]

India's national space agency, the Indian Space Research Organisation, launched Chandrayaan-1, an uncrewed lunar orbiter, on October 22, 2008.[53] The lunar probe was originally intended to orbit the Moon for two years, with scientific objectives to prepare a three-dimensional atlas of the near and far side of the Moon and to conduct a chemical and mineralogical mapping of the lunar surface.[54] The orbiter released the Moon Impact Probe which impacted the Moon at 15:04 GMT on November 14, 2008.[55] The orbitor was able to detect a widespread presence of water molecules in the lunar soil.[56] This mission was followed up by Chandrayaan-2, which launched on July 22, 2019, and entered lunar orbit on August 20, 2019. Chandrayaan-2 also carried India's first lander and rover, but due to a last minute technical glitch in the landing system, the spacecraft crash-landed.[57]

Chandrayaan-2 was followed by Chandrayaan-3, the third lunar exploration mission by the Indian Space Research Organisation. It also carried the lander named Vikram and the rover named Pragyan, and achieved the country's first soft landing near the south polar region of the Moon.[58][59][60]

United States

[edit]The Ballistic Missile Defense Organization and NASA launched the Clementine mission in 1994, and Lunar Prospector in 1998.

Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter · Moon

NASA launched the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, on June 18, 2009, which has collected imagery of the Moon's surface. It also carried the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS), which investigated the possible existence of water in the crater Cabeus. GRAIL is another mission, launched in 2011.

Following the decades-long lull in lunar exploration in the aftermath of the Cold War, the main push of US lunar exploration goals has coalesced under the Artemis program, formulated in 2017.[61]

Russia

[edit]On 10 August 2023, Russia launched the Luna 25 mission, its first mission to the Moon since 1976.[62] On 20 August, it crashed into the Moon after a guidance error that resulted in an anomalous orbit lowering maneuver.[63]

South Korea

[edit]South Korea launched the lunar orbiter Danuri on 4 August 2022, and it arrived at the Moon on 16 December 2022. This is the first phase of South Korea's lunar exploration program, with plans to launch another lunar lander and probe.[64]

Pakistan

[edit]Pakistan sent a lunar orbiter called ICUBE-Q along with Chang'e 6.[49]

Commercial missions

[edit]In 2007, the X Prize Foundation together with Google launched the Google Lunar X Prize to encourage commercial endeavors to the Moon. A prize of $20 million was to be awarded to the first private venture to get to the Moon with a robotic lander by the end of March 2018, with additional prizes worth $10 million for further milestones.[65][66] As of August 2016, 16 teams were reportedly participating in the competition.[67] In January 2018 the foundation announced that the prize would go unclaimed as none of the finalist teams would be able to make a launch attempt by the deadline.[68]

In August 2016, the US government granted permission to US-based start-up Moon Express to land on the Moon.[69] This marked the first time that a private enterprise was given the right to do so. The decision is regarded as a precedent helping to define regulatory standards for deep-space commercial activity in the future. Previously, private companies were restricted to operating on or around Earth.[69]

On 29 November 2018, NASA announced that nine commercial companies would compete to win a contract to send small payloads to the Moon in what is known as Commercial Lunar Payload Services. According to NASA administrator Jim Bridenstine, "We are building a domestic American capability to get back and forth to the surface of the moon.".[70]

The first commercial mission to the Moon was accomplished by the Manfred Memorial Moon Mission (4M), led by LuxSpace, an affiliate of German OHB AG. The mission was launched on 23 October 2014 with the Chinese Chang'e 5-T1 test spacecraft, attached to the upper stage of a Long March 3C/G2 rocket.[71][72] The 4M spacecraft made a Moon flyby on a night of October 28, 2014, after which it entered elliptical Earth orbit, exceeding its designed lifetime by four times.[73][74]

The Beresheet lander operated by Israel Aerospace Industries and SpaceIL impacted the Moon on April 11, 2019, after a failed landing attempt.[75]

Plans

[edit]Following the abandoned US Constellation program, plans for crewed flights followed by moonbases were declared by Russia, ESA, China, Japan, India, and South Korea. All of them intend to continue the exploration of the Moon with more uncrewed spacecraft.

India is planning and it is studying a potential collaboration with Japan to launch the Lunar Polar Exploration Mission in 2026–2028.

Russia also announced plans to resume its previously frozen project Luna-Glob, an uncrewed lander and orbiter, which was slated to launch in 2021 but did not manifest.[76] In 2015, Roscosmos stated that Russia plans to place an astronaut on the Moon by 2030, leaving Mars to NASA. The purpose is to work jointly with NASA and avoid a space race.[77] A Russian Lunar Orbital Station has been proposed to orbit the Moon after 2030.

In 2018, NASA released plans to return to the Moon with commercial and international partners as part of an overall agency Exploration Campaign in support of Space Policy Directive 1, giving rise to the Artemis program and the Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS). NASA plans to start with robotic missions on the lunar surface, as well as the crewed Lunar Gateway space station. As of 2019, NASA is issuing contracts to develop new small lunar payload delivery services, develop lunar landers, and conduct more research on the Moon's surface ahead of a human return.[78] Artemis program involves several flights of the Orion spacecraft and lunar landings from 2022 to 2028.[79][80]

On November 3, 2021, NASA announced it had picked a landing site in the lunar south polar region near the crater Shackleton for an uncrewed spacecraft that included NASA's Polar Resources Ice-Mining Experiment-1. The precise location was termed the Shackleton Connecting Ridge, which has near-continuous solar exposure and line-of-sight with Earth for communication.[81]

ESA's Moonlight Initiative aims to create a small network of communication and navigation satellites orbiting the Moon to support the Artemis landings.[82] These would enable communication with Earth even when out of direct line-of-sight. They would also provide navigation signals similar to the Global Positioning System on Earth, requiring precision timekeeping. Moonlight planners have proposed creating a new time zone for the Moon for this purpose, culminating in the introduction of the Coordinated Lunar Time standard in 2024.[83] Due to the lower gravity and relative motion, time passes more quickly on the Moon, making every 24-hour period elapse 56 microseconds early when measured from Earth.[84]

See also

[edit]- Artemis program

- Colonization of the Moon

- Tourism on the Moon

- Lunar outpost (NASA)

- International Lunar Exploration Working Group

- List of artificial objects on the Moon

- List of Apollo astronauts

- List of lunar probes

- List of missions to the Moon

- Lunar resources

- Moon landing

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

- Starship HLS

References

[edit]- ^ "Lunar Sample Overview". Lunar and Planetary Institute. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- ^ Lyons, Kate. "Chang'e 4 landing: China probe makes historic touchdown on far side of the moon". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ "China successfully lands Chang'e-4 on far side of Moon". Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (January 10, 2024). "China's Chang'e-6 probe arrives at spaceport for first-ever lunar far side sample mission". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on May 3, 2024. Retrieved June 25, 2024.

- ^ Dangwal, Ashish (November 22, 2023). "1st Country With Lunar Outpost, Competition 'Heating-Up' Between US-Led Artemis & China's ILRS". Latest Asian, Middle-East, EurAsian, Indian News. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ Boyle, Rebecca (July 9, 2019). "Ancient humans used the moon as a calendar in the sky". Science News. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ Burton, David M. (2011). The History of Mathematics: An Introduction. Mcgraw-Hill. p. 3. ISBN 978-0077419219.

- ^ "Lunar maps". Archived from the original on June 1, 2019. Retrieved September 18, 2019.

- ^ "Carved and Drawn Prehistoric Maps of the Cosmos". Space Today. 2006. Archived from the original on March 5, 2012. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (1992). Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary. The British Museum Press. p. 54, 135. ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2017.

- ^ "Nebra Sky Disc". State Museum of Prehistory. Retrieved September 27, 2024.

- ^ Simonova, Michaela (January 2, 2022). "Under the Moonlight: Depictions of the Moon in Art". TheCollector. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- ^ Meller, Harald (2021). "The Nebra Sky Disc – astronomy and time determination as a source of power". Time is power. Who makes time?: 13th Archaeological Conference of Central Germany. Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Halle (Saale). ISBN 978-3-948618-22-3.

- ^ Concepts of cosmos in the world of Stonehenge. British Museum. 2022.

- ^ Bohan, Elise; Dinwiddie, Robert; Challoner, Jack; Stuart, Colin; Harvey, Derek; Wragg-Sykes, Rebecca; Chrisp, Peter; Hubbard, Ben; Parker, Phillip; et al. (Writers) (February 2016). Big History. Foreword by David Christian (1st American ed.). New York: DK. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-4654-5443-0. OCLC 940282526.

- ^ O'Connor, J.J.; Robertson, E.F. (February 1999). "Anaxagoras of Clazomenae". University of St Andrews. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c Needham, Joseph (1986). Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and Earth. Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 3. Taipei: Caves Books. p. 227; 411–416. ISBN 978-0-521-05801-8.

- ^ Hayashi (2008), Aryabhata I.

- ^ a b Langermann, Y. Tzvi (1985). "The Book of Bodies and Distances of Habash al-Hasib". Centaurus. 28 (2): 111–112. Bibcode:1985Cent...28..108T. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0498.1985.tb00831.x.

- ^ Toomer, G. J. (December 1964). "Review: Ibn al-Haythams Weg zur Physik by Matthias Schramm". Isis. 55 (4): 463–465. doi:10.1086/349914.

- ^ Montgomery, Scott L. (1999). The Moon & the Western Imagination. University of Arizona Press. pp. 75–76. ISBN 9780816519897.

- ^ Van Helden, A. (1995). "The Moon". Galileo Project. Archived from the original on June 23, 2004. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c "The Galileo Project". Archived from the original on September 5, 2007. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Энциклопедия для детей (астрономия). Москва: Аванта+. 1998. ISBN 978-5-89501-016-7.

- ^ Robens, Erich; Stanislaw Halas (February 16, 2009). "Study on the Possible Existence of Water on the Moon" (PDF). Geochronometria. 33 (–1): 23–31. Bibcode:2009Gchrm..33...23R. doi:10.2478/v10003-009-0008-2. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ^ "First image of the Moon taken by a U.S. spacecraft". NSAS NSSDC Image Catalog. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ "Luna 1". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive.

- ^ NASA.gov.

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (May 25, 1961). Special Message to Congress on Urgent National Needs (Motion picture (excerpt)). Boston, MA: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Accession Number: TNC:200; Digital Identifier: TNC-200-2. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ NASA.gov.

- ^ NASA.gov – 24 January 2020.

- ^ "LEK Lunar Expeditionary Complex". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ "DLB Module". astronautix.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ "Kaguya (SELENE)". JAXA. Retrieved June 25, 2007.

- ^ Sample, Ian (January 19, 2024). "Japan's Slim spacecraft lands on moon but struggles to generate power". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on January 19, 2024. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ Crane, Leah. "Japan's SLIM moon lander has shockingly survived a third lunar night". New Scientist. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- ^ "SMART-1 Impacts Moon". ESA. September 4, 2006. Archived from the original on October 25, 2006. Retrieved September 3, 2006.

- ^ David, Leonard (March 4, 2003). "China Outlines its Lunar Ambitions". Space.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2006. Retrieved March 20, 2006.

- ^ Sun, Zezhou; Jia, Yang; Zhang, He (2013). "Technological advancements and promotion roles of Chang'e-3 lunar probe mission". Sci China Tech Sci. 56 (11): 2702. Bibcode:2013ScChE..56.2702S. doi:10.1007/s11431-013-5377-0. S2CID 111801601.

- ^ China launches historic mission to land on far side of the Moon Stephen Clark, Spaceflight Now. 07 December 2018.

- ^ Devlin, Hannah; Lyons, Kate (January 3, 2019). "Far side of the moon: China's Chang'e 4 probe makes historic touchdown". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 6, 2019.

- ^ China's Farside Moon Rover Breaks Lunar Longevity Record. Leonard David, Space.com. 12 December 2019.

- ^ Morgan McFall (26 Feb 2020) China's lunar rover finds nearly 40 feet of dust on the far side of the moon

- ^ Nowakowski, Tomasz (August 9, 2017). "China Eyes Manned Lunar Landing by 2036". Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (September 25, 2017). "Long March 5 failure to postpone China's lunar exploration program". SpaceNews. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (November 1, 2019). "China targets late 2020 for lunar sample return mission". SpaceNews. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ "China's Chang'e-5 mission returns Moon samples". BBC News. December 16, 2020. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- ^ Andrew Jones [@AJ_FI] (April 25, 2023). "China's Chang'e-6 sample return mission (a first ever lunar far side sample-return) is scheduled to launch in May 2024, and expected to take 53 days from launch to return module touchdown. Targeting southern area of Apollo basin (~43º S, 154º W)" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ a b Jones, Andrew (January 10, 2024). "China's Chang'e-6 probe arrives at spaceport for first-ever lunar far side sample mission". SpaceNews. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (May 6, 2024). "China's Chang'e-6 is carrying a surprise rover to the moon". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on May 8, 2024. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ Jones, Andrew (June 1, 2024). "Chang'e-6 lands on far side of the moon to collect unique lunar samples". SpaceNews. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Seger Yu [@SegerYu] (June 1, 2024). "落月时刻 2024-06-02 06:23:15.861" (Tweet) (in Chinese) – via Twitter.

- ^ "NDTV.com: Perfect start, Chandrayaan-1 ready for next step". Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ^ "Chandrayaan-1 Scientific Objectives". Indian Space Research Organisation. Archived from the original on October 12, 2009.

- ^ "India sends probe on to the Moon". BBC. November 14, 2008. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ^ Lunar Missions Detect Water on Moon Archived 2009-10-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Chandrayaan – 2 Latest Update – ISRO". www.isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on September 8, 2019. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Welle, Deutsche. "India spacecraft first to land on moon's south pole".

- ^ "India lands spacecraft near south pole of moon in historic first". amp.theguardian.com. August 24, 2023. Archived from the original on August 24, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Bureau, The Hindu (July 6, 2023). "Chandrayaan-3 launch on July 14, lunar landing on August 23 or 24". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "NASA: Moon to Mars". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "NASA: Moon to Mars". nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ "Russia is back on the lunar path. A rocket blasts off on its first moon mission in nearly 50 years". August 11, 2023.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (August 19, 2023). "Luna-Glob mission lifts off". RussianSpaceWeb. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Danuri, South Korea's first Moon mission". The Planetary Society.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (January 24, 2017). "For 5 Contest Finalists, a $20 Million Dash to the Moon". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 15, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ Wall, Mike (August 16, 2017), "Deadline for Google Lunar X Prize Moon Race Extended Through March 2018", space.com, archived from the original on September 19, 2017, retrieved September 25, 2017

- ^ McCarthy, Ciara (August 3, 2016). "US startup Moon Express approved to make 2017 lunar mission". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on July 30, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ "An Important Update From Google Lunar XPRIZE". Google Lunar XPRIZE. January 23, 2018. Archived from the original on January 24, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ a b "Moon Express Approved for Private Lunar Landing in 2017, a Space First". Space.com. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (November 29, 2018). "NASA's Return to the Moon to Start With Private Companies' Spacecraft". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2018.

- ^ "First commercial mission to the Moon launched from China". Spaceflight Now. October 25, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ "China Readies Moon Mission for Launch Next Week". Space.com. October 14, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ "Saft lithium batteries powered the 4M mini-probe to success on the world's first privately funded Moon mission" (Press release). paris: Saft. January 21, 2015. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2015.

- ^ Moser, H. A.; Ruy, G.; Schwarzenbarth, K.; Frappe, J. -B.; Basesler, K.; Van Shie, B. (August 2015). "Manfred Memorial Moon Mission (4M): development, operations, and results of a privately funded, low cost lunar flyby". 29th Annual AIAA/USU Conference on Small Satellites. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ^ Lidman, Melanie. "Israel's Beresheet spacecraft crashes into the moon during landing attempt". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Covault, Craig (June 4, 2006). "Russia Plans Ambitious Robotic Lunar Mission".

- ^ "Russia to place man on Moon by 2030 leaving Mars to NASA". June 27, 2015.

- ^ Warner, Cheryl (April 30, 2018). "NASA Expands Plans for Moon Exploration". NASA. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ "National Space Exploration Campaign Report" (PDF). NASA. September 2018.

- ^ "Moon to Mars | NASA". June 25, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- ^ "NASA picks landing site at the moon's south pole for ice-drilling robot". Space.com. November 5, 2021.

- ^ What is ESA’s Moonlight initiative?

- ^ Ramirez-Simon, Diana (April 3, 2024). "Moon Standard Time? Nasa to create lunar-centric time reference system". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ If daylight saving time seems tricky, try figuring out the time on the moon .